NEW Story: Cocktail

Tattoos of Violence on Quiet Men

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

Where tattoos had once been an indication of class and work, they were now uncommon. Both class and work had been abolished. Tattoos were almost never seen in the prism of ordinary Vekllei life, but in less savoury occupations they were found where utopian concessions collide with violence and memory.

Baron rolled up his sleeves and laid them out for her. You could accuse him of many things — he was a reticent bloke — but he was never dishonest with Tzipora. She was as much a companion as a daughter, and he treated her with the respect he’d afford any close colleague or friend. His upper arm was marked with faded illustrations from a previous chapter of life. Most obvious was a dragon that looked like it had been done professionally, or at least by a comrade who’d had some experience. It was intricate and artful. The rest were simple words or illustrations, maybe done by the man himself. Holding her tongue about the dragon tattoo, which demanded attention in its colour and scale, she asked about three dots that matched the patterns of her shirt.

“Those are for Amelie. I mentioned her, didn’t I? She was my sister — she would have liked you, too. She had a strange sense of humour.”

They marked the grave of his sister who passed as a teen-ager from tuburculosis. It was a common outbreak in the poverty that followed the First Atomic War. She was fifteen — the Vekllei lifespan is measured in sets of five. Beneath it was a dagger, or improvised military cross, listing the initials of two friends of his and his years of service. “All done,” he told her, “while black-out drunk.”

She asked about his friends, and where they were, and he told her he didn’t know. “It’s true. That’s how service overseas goes sometimes. Look how long it took for me to get back here. I wouldn’t recognise them.” He paused for a moment, and raised his eyebrows. “Most likely, they’re dead.”

Within the Chinese dragon, illustrated cleanly with improvised equipment, lay a history of sweltering heat and combat. This one was a soldier’s tattoo, proud and impossible to ignore. You don’t give much thought to scarring your skin if you’re about to die. She did not know how long he was there, or in what capacity, because he did not talk about his time in the army. She just knew he was young — maybe a few years older than her.

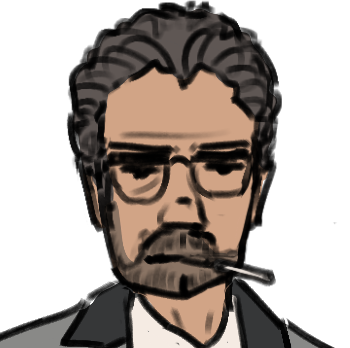

She liked his tattoos. For the thirty years she would know him, he was outwardly a quiet and thoroughly unextraordinary man. He took part in no great pleasures except a glass of wine on Friday evenings and a movie with Zelda on Sunday. Not once did he ever raise his voice at her. He smoked occasionally, and a pipe on weekends. But when he rolled up his sleeves after supper to smoke his pipe, and watch the evening from their eighth-floor balcony, the snake climbing the dagger was visible on his forearm. And behind that dagger, and that snake, there was a filthy room in Ariquemes, and a baby’s cry, and blood. A sinister revelation settled on the room.

As Zelda would once explain, you might go to a friend’s party or parent-teacher, and all the other dads would see hers and think he looked like a professor or bank teller. She liked to think they gave no regard to him at all — he looked like a quiet, pleasant, nothing-person. But if he reaches for his left sleeve and rolls it up, that all changes. He reveals himself to be a figure of death.