NEW Story: Sunday Morning

A New Generation

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

Children of the children of the bomb — a generation of war-babies born in peacetime. That was how they thought of themselves. Their grandparents and great-grandparents had lived through the war and the occupation, and so they had inherited the burden of Vekllei’s future as a country of long-sufferers, visionaries, and dispossessed.

Some Marxist continental intellectual had said something a half-century ago about the right way to teach children, and the idea had probably caught the ear of some commissar of the Vekllei interim government, who perhaps passed it along to some bureaucrat rebuilding the government schools. As a result, Vekllei children only go to school three or four days a week. There, they spend only a few hours a day in classrooms. There is, after all, no real workforce for which they are being primed. Vekllei’s labour economy is a play-fantasy, and so they mostly learn how to play.

It is not designed to ‘free’ children — Vekllei schools have hierarchies, punishments and are mandatory — instead, the primary goal of education is self-discovery and self-respect. It is precisely these qualities that benefit most the modern Vekllei economy, which is heavily automated and competes internationally through the product of its participatory creative thinking.

There is no grading system in Vekllei — all classes are passed or failed. The value of compulsory education through government schools, then, is the socialisation of boys and girls with others boys and girls, and the availability of equipment and facilities to participate in extracurricular activities. This is the real body of Vekllei school life — its clubs, societies, and individual associations. Many professional photographers in this country discovered an affection for photography before they turned 15 years old, through exposure to it in school. These resources, and the need to socialise children with others, are the reasons the Vekllei government continues to universalise government schooling, even alongside home-schooling or independent/religious education.

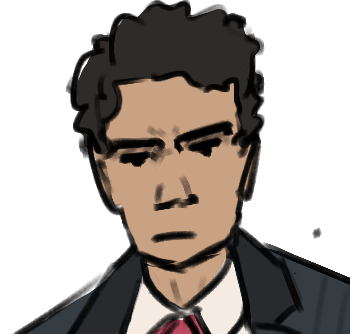

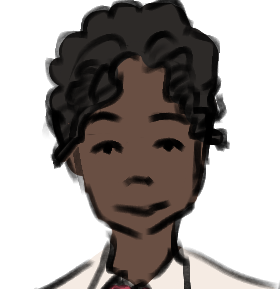

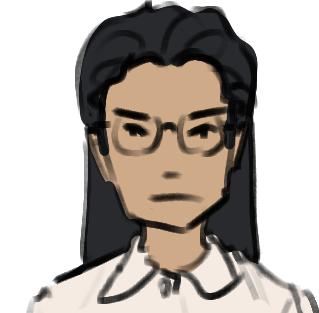

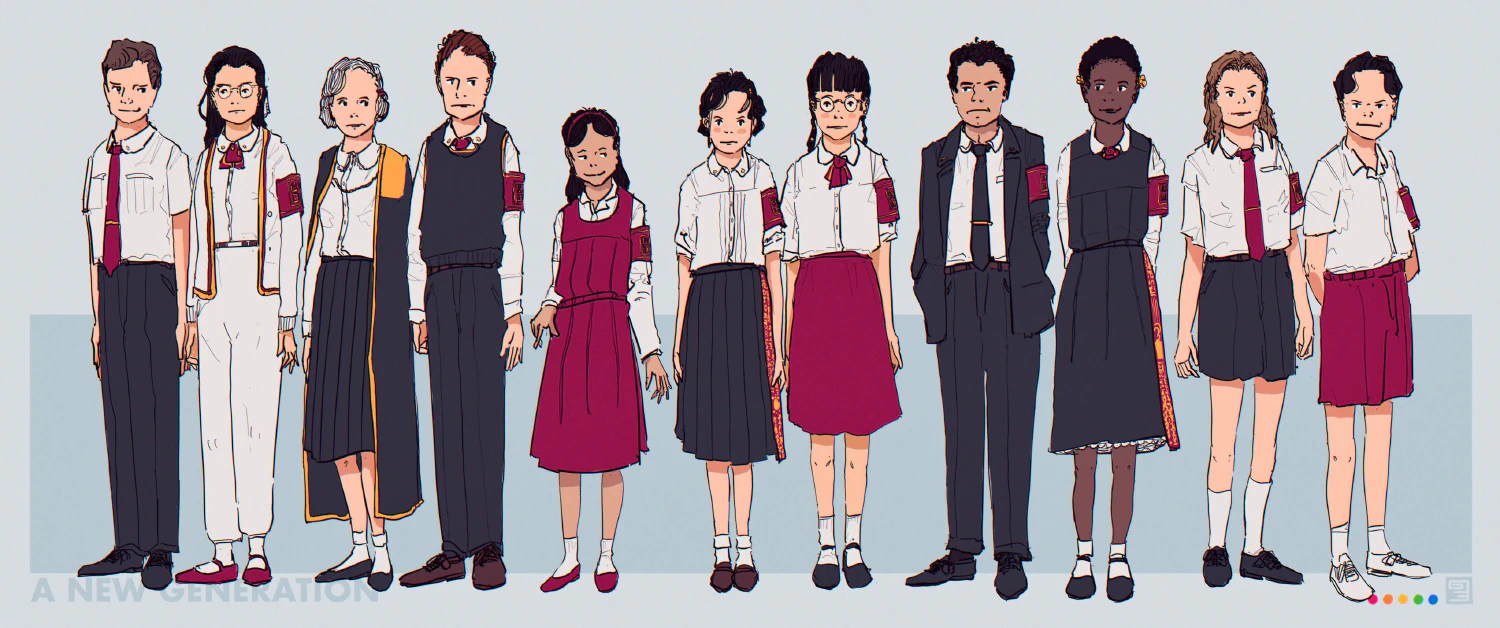

Depicted here are the good-natured youth of the new generation in school uniform — a topic we’ve visited before. All students in Vekllei wear the same uniform, including at university. The uniforms themselves are not designed specifically to regulate appearance — and to this end, schools do not have dress codes regarding hair or cultural/religious accessories including jewellery.

Discard any assumptions about the meaning behind the colour or style of their clothes — all variations depicted here can be worn by whomever, no matter their age, school or association. In fact, school uniforms are not provided directly by schools — they are found at department stores, on the rack alongside suits and dresses. Because of this fact, specific styles of shirt, trousers, socks and shoes vary between students — and are acceptable as long as they meet the basic requirements of the uniform. This intersection of control and anarchy can be found widely throughout broader Vekllei society, and is an interesting example of how the basic principles of the “Vekllei way of life” are reflected in the microscopic mundanities of life and foundations of national culture simultaneously.