NEW Story: Sunday Morning

The Race for Inefficiency

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

✿ This article was featured in Issue #3 of the Atlantic Bulletin

Vekllei’s advocation of austerity, apathy, and playfulness as economic principles #

This post is about the economy of Vekllei. It’s a bit of a long one. If you have any questions, just ask.

Overview of the Bureau System #

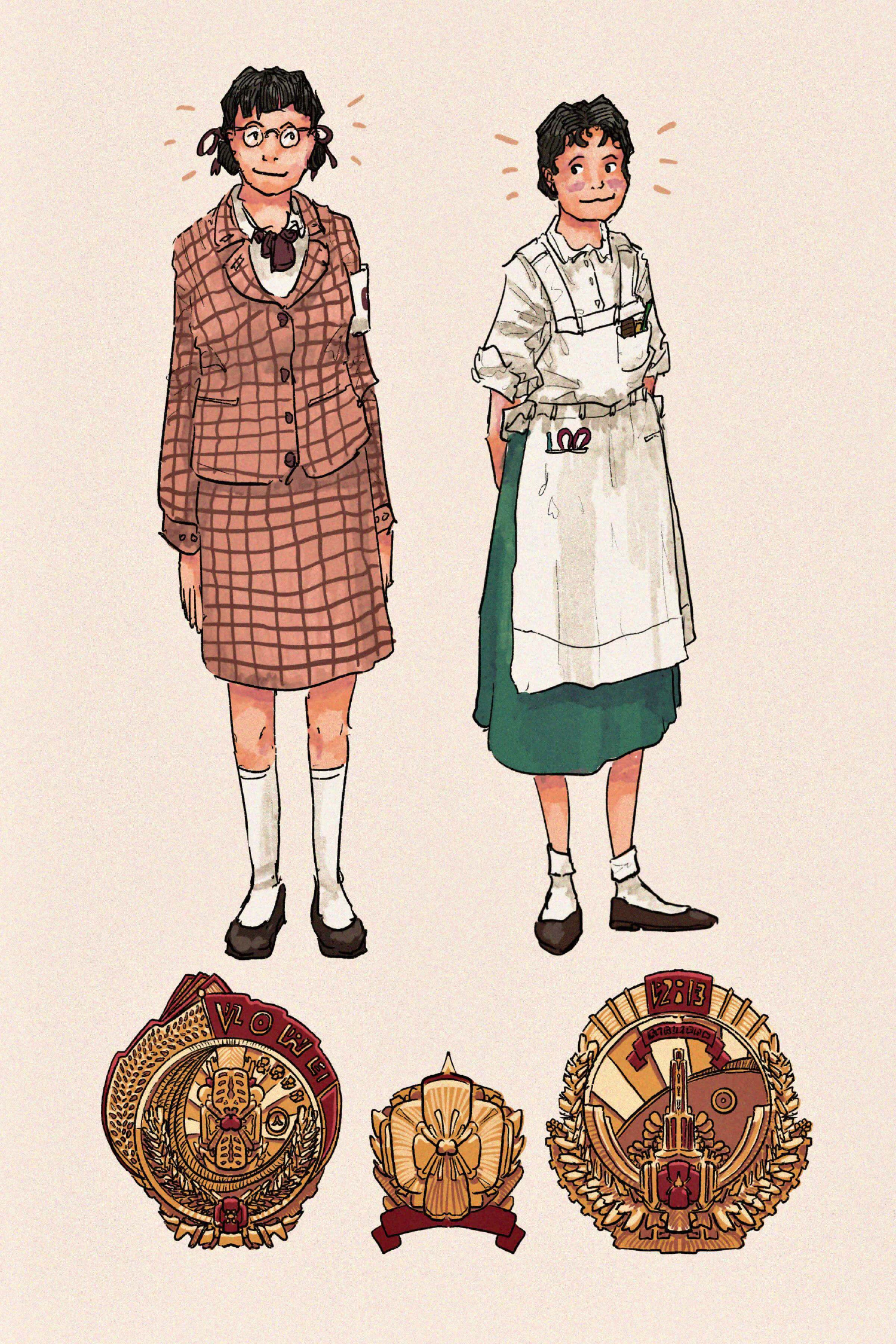

There are many thousands of companies busy with work in Vekllei. The vast majority of these companies are single-person shops (S.p.A., or senrouiva pettetie anaproiouya). Also common are wobbly shops, or co-operative businesses (S.q.A., or senrouiva qualitie anaproiouya). The largest of the non-bureau companies are village factories (S.p.M., or senrouiva persimonaya manufacturie).

The bureau-level world is full of company mastheads that emphasise modernity, dynamism and progress. Vekllei’s “private businesses”, however, tend to be local in taste. The vast majority of S.p.A. and S.q.A. businesses bear the family names of their founders — Desmesyo S.p.A., Risyiouisnesn Home Machines S.q.A., etc. Their legal denominations are almost always affixed to the end of their nameplates.

Their senrouiva designation marks them as non-bureau businesses. A bureau, as a reminder, is simply the top-level organisation of a trade union that organises business in the country. In practice, it means that a company is responsible to the political organs of the country. Although independent from the government, bureau business is inextricably entwined in government concern and runs parallel to it.

Senrouvia businesses are also part of the bureau structure, but are in practice not managed directly by them. They are usually united in local concern by so-called petty bureaus; small cooperative organs that safeguard local interest and business. These petty bureaus are often at odds with the bureau organs proper, and so even though they are part of the same structure, they are fundamentally political opposed.

So what is sort of business goes on in a bureau proper?

There are two common categories of so-called “bureau firms”. You have state industries (S.A., or societie indastrie), which deal with manufacturing and exploitation of resources that require direct management by a public organ. You’ll already be familiar with several — General Reactor, Comen Aeroyards S.A., Farmer’s Syndicate S.A. to name a few.

You also have state requisites (A.r., or requoisesiasn amourisocietie), which refer to the vast government-operated organs made up six categories primarily.

- Utilities (A.r.Un.)

- Transport (A.r.R.)

- Education (A.r.E.)

- Local healthcare (A.r.F.)

- Construction (A.r.Lo.)

- Automation (A.r.M.)

Yes — education is not organised as a government department, but a bureau business. Other state responsibilities are folded directly into government departments — war, intelligence, healthcare, police, fire, and the mint are all managed directly by the government.

Argument #

With the legal division of enterprise laid out, let us examine again the four precepts of the Vekllei economic ideology.

- Self-management and self-interest through Sundress Municipalism.

- Classification of property as an independent social organ, like nature.

- Abolishment of currency and currency-substitutes. Participatory employment.

- Economic feminisation.

These four principles reveal a great deal about the character of the country, and stand largely at face value. There is an interest in chasing the promises of modernity while deconstructing its metaphysical constructions, through the abolishment of exchange-value, property and the overhaul of gender-economics. There are anarchist gestures in each principle, yet it is obvious that the product of these values complexify the conventional anarchist imagination. This is part of a series of contradictions — between free and planned markets, between internationalism and provinciality, between man and woman, between freedom and security.

Austerity #

The bureau system is plagued by inefficiencies, arising from logistic systems premised on warehousing, poor Coasean bargaining between petty bureaus and proper bureaus, a political emphasis on macroeconomic outcomes, a decoupling of aggregate demand and national economic output, cultural intolerance for Pareto inefficiencies, etc.

Luxury goods often vary in both supply and access, and economies are often severely localised to the point of provincialism, meaning that Vekllei has failed to transition reliably to a modern consumer society. The inhabitants of the Montre borough most often eat seafood because speciality meats, especially authentic red meat, are scarce. The opposite is true in Yana. Clothes are repaired and regifted, appliances are available only from regional outlets usually located in the same city as the factory, and culture and diet are fiercely regional.

This is, in part, a result of unflinching national austerity and the sublimation of artificial markets prompted by Vekllei’s gold-based auxiliary currency, which necessitates meeting debt obligations for its strength internationally. There is a belief in Vekllei that the wealth of the country allowed the abolition of the currency — in fact, the opposite is true. The abolition of currency allows a permanent wealth that compensates for the inefficiencies of the bureau system. The bureau firms do not pay their workers — on paper, there are no expenses for anything beyond raw commodity exchange. This is how Vekllei’s largest companies — and, per the bureau system, its government — remain solvent.

Austerity is a cultural force, too — the scarcity of luxury goods inflates their social value, where comforts and necessities are largely abundant in automation. It creates an unimportant hardship that keeps Vekllei people forward-facing, lean, and ambitious. To acquire Picco S.p.A.’s iconic lounge chairs, you have to travel to their outlet in Horn, hundreds of kilometres from the capital area. There is no motivation for a craftsman to meet demand — there is no petty consumption, either. To own a Picco chair means you have understood its cultural value, utility and craftsmanship, and have made the effort to find and transport one to your home. Inconvenience, and by extension, austerity, is celebrated as a “trial of ownership.” Objects are very important in Vekllei, and craftsmanship is highly valued, and so people like to surround themselves with hand-made, sublime things wrought not just by the labour of the artisan, but their own effort to acquire it.

Petty austerity instills a national sentiment that tells the ordinary Vekllei person they are hardier than the ordinary American or European, even if the wealth of the ordinary Vekllei person is much greater than that of the ordinary American or European.

Apathy #

Despite a vast, loosely organised private market in the senrouiva categorisation, Vekllei does not reward entrepreneurial ambition. Ambitious people are funnelled into positions of power in bureau firms and political office, but the founding of S.p.As and S.q.As is rarely motivated by a desire for influence or power. Indeed, artisanal S.p.As are often incapable of the sort of economies of scale needed for expansion. Vekllei instead relies on a sort of economic apathy, in which aggregate demand and productivity are spurned for immediate interest and pleasure.

This ensures that

- luxury products remain creative, personal works per Upen’s insistence on the symbiosis of labour and product

- the private senrouiva market is not capable of threatening the provincialism of Sundress Municipalism, which might make a commodity universally accessible and threaten to introduce generic consumer society into Vekllei life

- the private senrouiva market under petty bureau organisation does not threaten the organised de facto monopolies of the bureau companies

If Vekllei has replaced the commodity with the object, then it is through economic apathy that they have ensured objects will never again become commodities. Just as the ordinary Vekllei person is apolitical, so too are they apathetic towards change in their purchasing habits, favouring small, inconvenient and personal brands over those exploiting aggregate demand. In a sense, this also contributed to the popular Vekllei term product atheism, in which the metaphysics of products are dismantled and rearranged into social forms.

In this sense, the apathy is found on both ends — within the senrouiva business owner, who is provided little upward mobility to satisfy ambition beyond local and regional expansion, and within the consumer, who recognises products only within cultural and social dimensions. Neither is conducive to a functioning, fair market on an interregional scale.

Play #

Play is the foundational motivation of most work in Vekllei. There are existential motivators, too — a desire to wield power, or professional legacy — but in many professions it is play by which a Vekllei person justifies labour. It is also why work is fiercely protected by petty bureaus and other labour organisations — work is their connection to wider society, and that connection is held sacred in Upen.

It is through work as play that Vekllei is able to justify the employment of children. Financial motivations for work have all but disappeared — in its place, the workplace has to convince people to work. There are few state protections for businesses unable to maintain a workforce, either — it is one of the most common reasons for the shuttering of a company. The boss must convince his workers to stay, and so a total inversion of power has occurred.

In place of money, there is prestige, and in prestige there is myth. Few people have genuine interest in Fordism. Many more are attracted to the hand-crafted furniture of Picco S.p.A., and becoming recognised as a builder of great things. In a sense, a person “acts out” the role of a craftsman, in the same way a person “acts out” the role of a police officer, or “acts out” life as a pilot.

In this system, the childish spirit of recreation, duty and “the adult world” is acted out by millions of Vekllei people each day. Seeds planted by a child play-acting as a farmer continue to grow, and so too does the Vekllei economy feed its population through the intersection of fantasy and labour. At this point it is obvious that play is not fantasy at all, but in fact a motivation for labour as genuine as profit. Where it falls short, in hard, disempowering jobs, it is automated and conscripted through the mandatory service system. As it is often described:

“The Bureau System is labour-intensive where wanted, alleviated by industrial machinery where preferred, and automated where necessary.”

In its wake are states of play, and through play comes a decent framework for living, obvious in the basic satisfaction of the Vekllei people.