NEW Story: Sunday Morning

The Face of War in the 21st Century

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

This is a story about Vekllei’s consumption and disposal of soldiers through her foreign fighting force. You can read more about the Vekllei army in these old posts here and here.

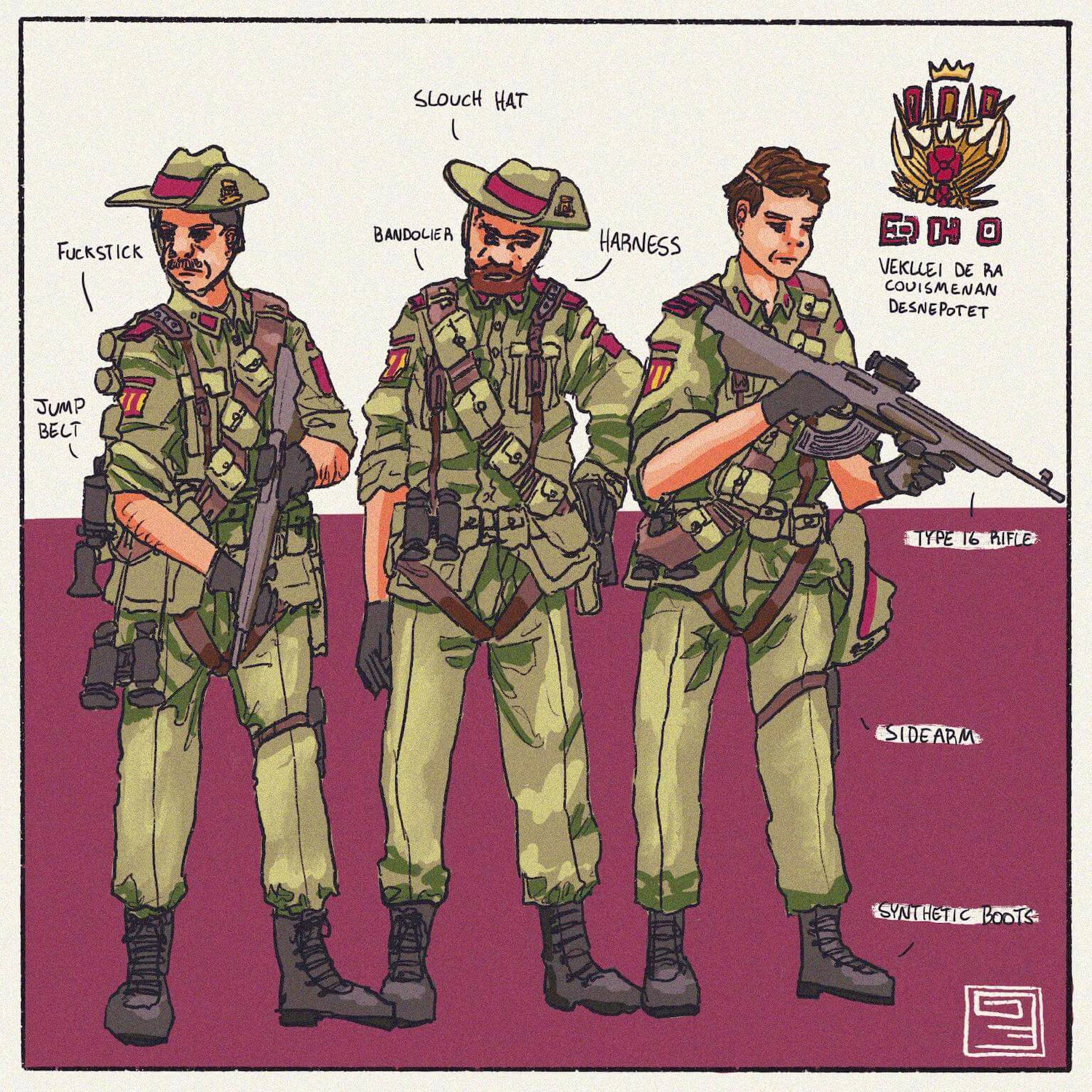

The Vekllei de ra Couismenan Desnepotet, or the Vekllei Foreign Army, is an exclusively foreign fighting force employed by the National War Bureau. It accepts any person between the ages of 18 and 35. After five years or being wounded, the soldier is granted Vekllei citizenship, making the Foreign Army one of the only guaranteed ways to secure citizenship in the country. Many thousands apply each year, but only a few hundred are chosen to enter training. Out of those hundred, almost all recruits have previous military experience, and many have spent time in conflict zones as mercenaries or special forces.

A Vekllei soldier is called a “Macker,” or “Macka,” which is Vekllei slang for a tool or implement (with origins most likely in the useless colonial wars of a century ago), and the fighters of the Foreign Army share this name. Macker slang is called Mackanese, and serves as a colourful argot that distinguishes military people from the general population.

The Foreign Army recruits are given a very different style of training to those at home. Where Vekllei people are egalitarian, laconic, and suspicious of authority, foreign recruits are taught to reverently serve the Army as an institution and maintain their status as elite soldiers. Vekllei has no qualms about allowing women to enlist in its special forces, and they are treated the same as male soldiers. Their numbers remain low among the Foreign Army population, but those that succeed are very skilled soldiers.

Soldiers of the Foreign Army are stationed abroad, and command areas of Vekllei political or economic interest. Almost eighty percent are stationed in the so-called “quadrilateral of poverty,” which has corners in Hong Kong, Darwin, Johannesburg, and Casablanca. Within this shape you’ll find the interests of the world’s powers, pushed to the brink following the collapse of oil and an extraordinarily expensive arms race for over a century.

While on a mission, unless food is acquired by other means, mackers eat pills. They carry three kind of pills: vitamin and performance-enhancing supplements (usually amphetamines), water disenfectants, and growables. Growables are capsules that, when mixed with water, solidify into a sort of paste that mackers call ‘remen soup,’ after the male prime minister of Vekllei (Vekllei has both a male and female head of state). Although they come in several flavours, they invariably have the texture of cold, watery gruel and are never eaten outside of missions.

In addition, all fighting folk of the Foreign Army carry “fucksticks,” a deliberately crude transliteration of “fox-sticks” or “explosive fox-hole diggers.” The firing end of a fuckstick is placed against asphalt, earth, or a wall, and after a short fuse it craters whatever is unfortunate enough to be on that end of it. In a grassy field, it will provide an emergency foxhole in otherwise flat earth. In an urban environment, it will allow entry through walls (and potentially bring the whole structure down). In the desert, it will produce a huge plume of sand that will obscure the soldier.

Most spectacular of the fighting man’s equipment, which otherwise distinguishes today’s equipment from that of yesteryear, is the jump-belt. Up to ten propellent canisters feed two jets that enable an ordinary person of mild athletic ability to perform superhuman jumps. They are not jet-packs; indeed, jet-packs are dangerous, specialised equipment rarely used for combat operations. Instead, a tug of a rip-cord will allow an unencumbered soldier to jump several meters, or cross a gap of up to 30 feet. While in development, the jump-belt was imagined to revolutionise infantry combat; it would allow troops to leap into second-story windows or leap across rooftops. Perhaps, it was even theorised, that someday we might do away with parachutes altogether and use belts to land instead. In reality, the jump-belt is mostly used to cross open roads or avenues, or to escape incoming fire. They are enormously unwieldy, and inexperienced troops will almost always lose their balance. In the right hands, however, they have seen success in the battlefield.

The National War Bureau is not a naive organisation. Outwardly the Foreign Army are foremost a declaration of power, in the child’s masculine fantasy most warlike forces rely so heavily upon; recruits are told that they are beyond good and evil; that they do what needs to be done; that they are a vanguard in the face of the forever war. The iconography and legend of the Foreign Army relies so heavily upon the masculine and the mercenary for the same reasons that the reshaping of a person’s identity is an essential part of the recruitment process – to submerge a decent person into the raw language of power, and disguise the iconography of hero-worship from its praxis as a totenkopf. In a global climate where consumption has ravaged the national and spiritual identity outside of Vekllei, and force is normalised and glorified, the foreign army is legitimised and made innocent for their vast crimes across the poverty quadrilateral.

They carry on, doing “what needs to be done”. It is only once they are broken and emptied by five years of indiscriminate violence, for undeclared reasons in an undeclared war, that they are shipped into Vekllei and find themselves too broken to assimilate into domestic society. So they reenlist; they are the eternal soldiers of a forever-war.