NEW Story: Sunday Morning

Looking Good and Feeling Good

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

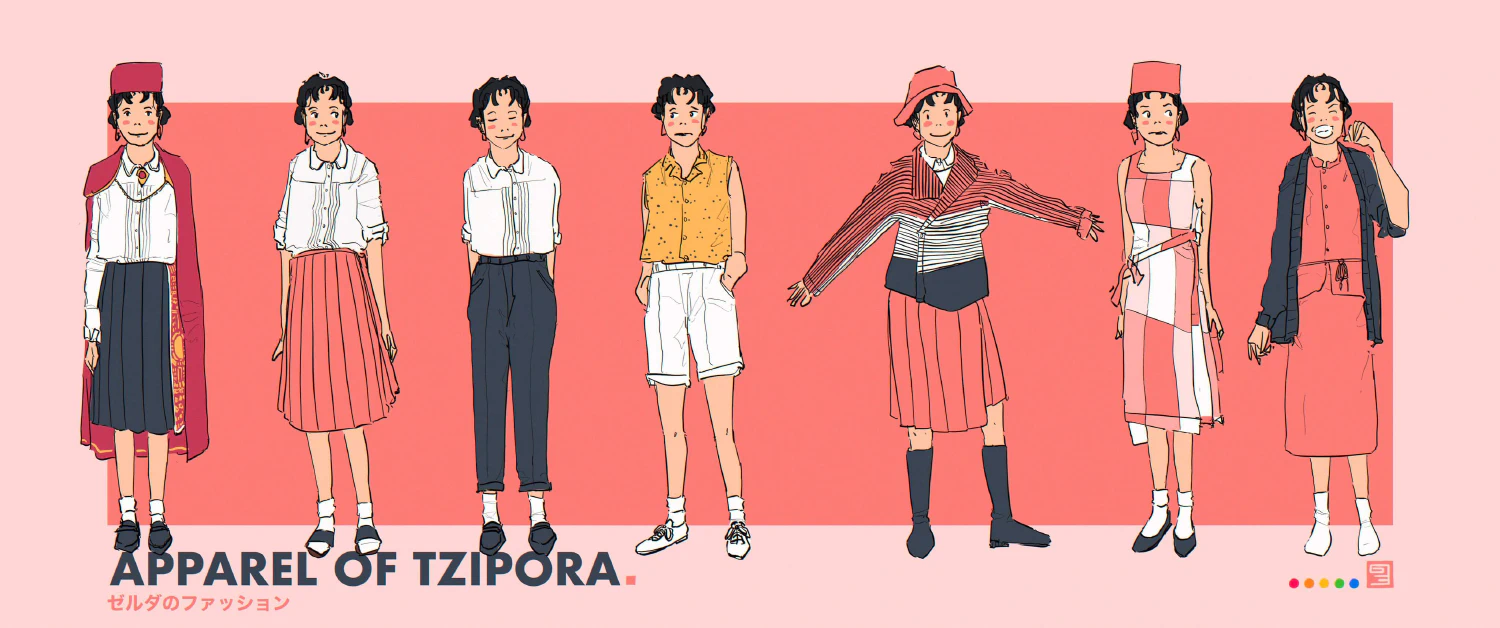

For most of her life, Tzipora dressed how she was told to dress. When she was a child, her clothes were provided. When she started school, the school clothed her. After school, heading west on the trains and picking up work as she found it, she wore whatever she could afford.

Up until her first steps inside the Cozetti Department Store in Vekllei, clothing was for gazing, not for being gazed at. Her new identity as a modern, middle-class girl had yet to emerge. It was a vacuum that needed filling in a new country where social behaviour drove your quality of life.

Clothing in Vekllei is manufactured by the same ideological forces that seek to “deindustrialise” the economic processes of the country — in other words, its broad physical decommodification. This included a championing of what they indigenously called “fashion atheism” or “antifashions,” meaning fashion that was not designed to be sold. This did not necessarily require a return to the woollen jumpers and seal pelts of yesteryear — just that clothing would return to the physical immediacy of art and architecture. It became what Vekllei people call “the decoration of ordinary life;” in other words, simply decorative and exclusively physical, and unburdened by intellectual or economic fetishisms.

This position is inherently conservative, in the sense that it was not supposed to change quickly, but the appearance of Vekllei’s “antifashions” did not advocate for traditional native styles specifically — indeed, many antifashions were quite radical both aesthetically and ideologically, and were pioneered by some of Vekllei’s most progressive art communities.

Employing Tzipora as an example here is not just a convenience of the project — she is a superb example of how the internationalist movement became a symbol of the global dispossessed. Her tastes were affected by her exposure to a unique style developed in the Vekllei-Italian immigrant design schools called “Nuova Grotessco Internazionale,” (Lit. International New Grotesque), which helped found her affection for simple clothing in simple colours.

“Grotesque” in this case comes from the Italian grotessco, a reference to forms so simple they could have been pulled from cave paintings. Although Tzipora was too sensible to ever seek them out, the showcase items of the Nuova Grotessco Internazionale movement were radical in their geometric simplicity — advocating androgynous silhouettes and “culturelessness” that looked like it came from nowhere and said nothing. Like all radical fashions, the dramatic conclusions of these ideas were moderated and filtered into general consumption in Vekllei, which went on to contribute to the popularity of new synthetic materials, space-age “cosmocorps” styles and bright geometric patterns common in the country.

Tzipora herself was never much for the grotesque, but she was very interested in internationalist styles. She had a few choice clothing items she reproduced in most of her outfits — she liked that her pleated shirts suggested nothing about her personality, her ethnic background, or her immigrant status. The pleated shirt is simply the “decoration of ordinary life.” It was inoffensive and uncomplicated. Such is the spirit of fashion atheism and the internationalist movement: clothing should suggest nothing intrinsic about you.

In Vekllei, this idea was seen as a critical liberator of women, and elsewhere, it was seen as an extension of international democracy and cooperation; an aesthetic of endless social mobility and freedom of expression. In Vekllei, where art was very radical and influenced heavily by continental designers, it was the ultimate symbol of postwar egalitarianism and recovery. The internationalist style has become the ‘new default’ of Vekllei fashion, obscuring its ideological origins through its presence in (and simple decoration of) everyday life.