NEW Story: Sunday Morning

Utopie Concrète

✿ Note from the Editor This essay was written in June 2021. Click here to see it as a post.

A New Style of Utopia #

I write introspectively about the project sometimes, as a means by which I consider what I’m doing and where my unconscious is leading me with this project. I have the instinct of someone who is over-educated and self-obsessed; someone who went to university, fell for the farce of serious media criticism, and failed to see that all media theorists are basically freaks. And there is a small truth buried in that hyperbole: it does in fact require a certain dysfunction to write books about the study of anime or television. You can become too close to something.

Utopie concrète, or ‘concrete utopia,’ is my phrase for how I work. I saw parallels with the manifesto of musique concrète, as described by Pierre Schaeffer:

Instead of notating musical ideas on paper with the symbols of solfège and entrusting their realisation to well-known instruments, the question was to collect concrete sounds, wherever they came from, and to abstract the musical values they were potentially containing.

Utopianism is much the same; it distills the concrete sentiment, concerns, and futures of a time and place and reproduces them in abstract in fiction. In a very straightforward way, my work (Vekllei, so-called) is an abstraction of real people, events, and things.

It also refers to the “feeling” of Vekllei, in a transcendental fashion. Utopianism is associated with very specific, loaded conceptions of perfection — cleanliness, symmetry, peacefulness, goodness, and impossibility. Vekllei is not any of these things consistently; it is like the raw concrete used in béton brut, and like raw concrete it discolours, weathers and crumbles in its exposure to reality and the march of time. You can see the formwork and imperfections in its product — not as a result of sloppy workmanship or carelessness, but because those things are beautiful; utopian in their own right.

At the risk of disfiguring these notes into a manifesto, the principles of utopie concrète might look something like this.

Principles of UTOPIE CONCRÈTE ■ #

- All things have dignity

- All things get dirty

- You must love it

To explain further:

- All things have dignity. You must take your “raw utopia” seriously — it has to be honest. In this sense, you must always aim to do your best for it. Consider your landscape and give your characters the respect you would anyone. If you dishonour them through sloppy work, you should feel embarrassed.

- All things get dirty. In order to ‘consider your landscape’ and ‘respect your characters,’ you must also recognise that these things need to live independently from your control. The activity of your utopia is what makes it alive, and also what makes it imperfect. Recognise the imperfections and celebrate them.

- You must love it. Utopias are very thoughtful and considered, but they can’t be intellectual. It must be intuitive — follow your heart.

UTOPIE CONCRÈTE ■ with Vekllei Characteristics #

There is a newer amendment to this section of the essay: Women, Vekllei

You already have the tools to create your concrete utopia — you just need to act on it. I have acted, and what has surfaced reveals a great deal about me, how I think and process the world, my anger and prejudices, my hopes and affections, and the pettiest of petty material interests.

Hayao Miyazaki, a great artist I admire deeply, was asked why his films starred heroines. He said:

At first, I thought “this is no longer the era of men…” But after ten years, I grew tired of saying that. I just say “because I like women.” That has more reality.

I mostly draw women, and there is not much good reason for it other than I like women.

I have said previously I’m deeply uncomfortable with the conceptual objectification of women, and the shallowness of girl-caricatures. Yet, when asked why my cast of characters are mostly women, I can only say that I like drawing women. That’s very revealing of the hypocritical discrepancy between essay rhetoric and my body of work. I try and give my characters dignity, but I also draw women and girls because they might look more interesting in a certain profession, or have better options for their clothes. Where is the dignity in being reproduced for how you appear in a picture? We can’t mistake “drawing women” for “representation of women.” This is a failing on my part.

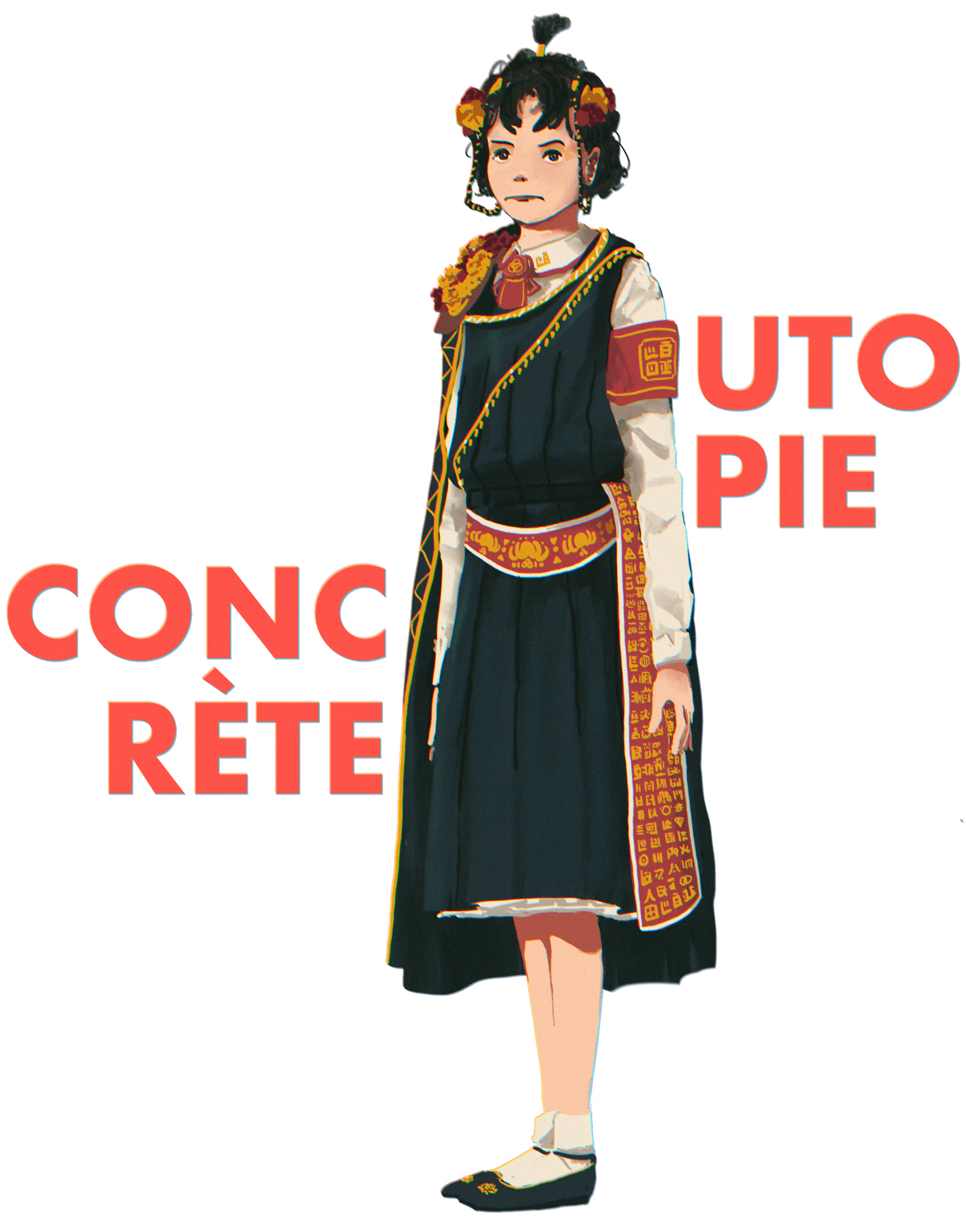

But I also think that Tzipora, the most egregious and unusual example of “using the appearance of women” in my project, is not much of a woman at all. She carries my anger, my obsessiveness, and lives my fantasy of a meaningful life. She is quite explicitly an author surrogate, although with a life of her own. She is also not supposed to be an authentic depiction of the experience of any woman — she is in fact closer to an anti-woman. She is so tomboyish, obsessive, and neurotic, that it’s hard to use her to explore conventional literary interests in ‘womanhood.’ Thank goodness for that — it’s not my place.

Creating Vekllei is my way of processing the goings-on of the world, and my lived experience day-to-day. In this sense, I prefer the clothes and appearance of women, and so in my utopia I draw women.

This is one of the interesting contradictions of utopianism. It is inherently egoistic, and can always be traced cleanly to the total worldview and personality of its author. But like most fiction, authors are eager to give life to their people and places, and would rather you not glimpse the man behind the curtain. Vekllei is fiction — Tzipora is a girl, and lives in Vekllei. Vekllei is also a utopia — Tzipora is me, and lives in my hopes, dreams, and anxieties. The contradiction is muted until authors start acting like the former is not a result of the latter, and that my personal experience does not affect who and what is depicted in Vekllei. This is true of all fiction — so let us not pretend cuteness is not a female burden, and my desire to draw nice clothes and interesting hairstyles is not an altruistic representation of women, no matter how well-intentioned my depictions may be.

This conversation is important only because Vekllei is important (to me), and the principles of utopie concrète are worth upholding — all things must have dignity.