NEW Story: Sunday Morning

A Universal Nostalgia

✿ Note from the Editor This thesis was completed in partial fulfillment of Bachelor of Media (Honours). It remains a good testament to my love of Ghibli. It was originally submitted in October 2020 and published in December 2020.

Abstract #

This thesis looks to argue for the value of spatiality in several films of the Studio Ghibli franchise in Japan. Literary space, much like the cartography of the real world, helps map meaning and locate the human body in the contemporary, postmodern displacement of old constructions. In this sense, there is a functional analogy in the physical map of a town, in which a reader is able to orient themselves and locate features of note around them. So too do the spaces of film provide functional markers of value, language, behaviour, style and story against space, recalling spatiotemporality as a vessel for each of them.

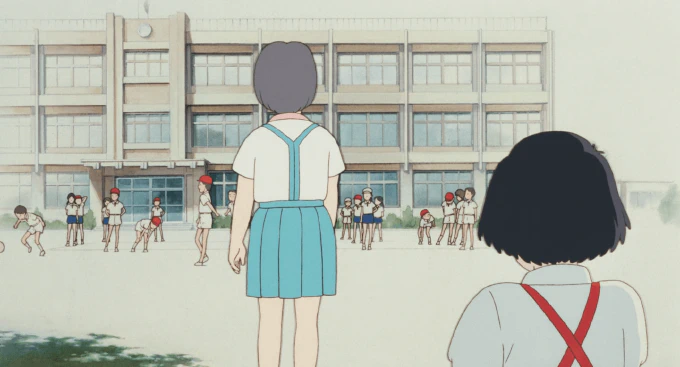

If all films are spatial, then many of Ghibli’s films are often utopian spaces. This is found within and without traditional utopian study — there are exemplary glimpses of pastoral, elegant utopia in My Neighbour Totoro (Tonari no Totoro, 1988), replicated in whimsy in other Miyazaki works like Kiki’s Delivery Service (Majo no Takkyūbin, 1989). There are however, more complicated utopias in the Ghibli catalogue that stray from orthodox imagination. Relevant to media inquiry, there are what this thesis recognises as utopias-by-appropriation in which the painterly depictions of urban Tokyo in Whisper of the Heart (Mimi o Sumaseba, 1995) or the beautiful illustrations of agrarian whimsy in Only Yesterday (Omoide Poro Poro, 1991) are decontextualised abroad and suspended in a traditional utopian ‘no-place’, where they are reinterpreted and rebuilt as fantasy. So it is that the real-world apartments of Tama Hills and the fields of Yamagata can become fictitious, spatial utopias.

And so, there are two questions of interest here. First, there is the question of employing the ‘spatial turn’ of textual analysis to Ghibli films, and whether this literary framework provides value in animation. Then, there is the question of how utopia-spaces manifest in Ghibli’s catalogue of films, and how the physical heritage and landscape of cinema is misplaced and then emerges anew in fantasy form for foreign (in the scope of this study, Western) audiences, where such works remain popular, thus manufacturing utopias where, perhaps, none exist in Japan.

Introduction #

The magic of the moving image reveals just how good our brains are at producing something from not much at all. Japanese anime, which is characterised by choppy frame rates, large plastic faces and gemstone eyes, somehow manages to produce authentic wonder and delight in audiences world-over. At some point in the production process, from cel drawing to foley work and voice dubbing, drawings come to life. There is perhaps no Japanese animation house in this business more celebrated and discussed in Western media scholarship than Studio Ghibli, which boasts a broad filmography that rattles off hit after hit. For many Westerners, some of whom go on to write about films in media studies, Ghibli was their gateway to anime. Their films are characterised by a deep respect for the life of cinema, and the authenticity of their characters. Other studios produce beautiful animation, and Disney films in particular feature more traditionally cinematic frame rates, but the lifelike, deeply friendly characters and worlds produced by Studio Ghibli are wholly unique experiences in cinema.

The main argument of this thesis is concerned with ‘place’, and how spaces are represented in animated films. There is also a utopian1 element at play here, which often assists this paper’s ‘spatial turn’ in textual analysis. The employ of these frameworks is not completely unthinkable, if perhaps a little unusual — utopia and spatiality are linked by their mutual concern with time and place. Literary spatiality is in part cartographical, often acting first as a crucible to navigate and understand events and then as a framework to contextualise those events against other phenomena. Rob Shields (1997) found that “spatial relations are constantly overcoded with social significance […] it comes as no surprise to most people that the where and the when of events are as significant as what those events are” (p.187). This reflects nicely the capabilities of utopian studies, which considers utopias to be social narratives bound to space and time. Lyman Sargent (1994), whose work has come to define much of utopia scholarship, wrote as much in his broad taxonomies of utopia, arguing the “general phenomenon” of utopianism is “social dreaming — the dreams and nightmares that concern the ways in which groups of people arrange their lives and which usually envision a radically different society than the one in which the dreamers live” (p. 3). In fact, this dependence on spatiotemporality is deeply ingrained in the tradition of utopian studies, from Karl Mannheim’s 1929 Ideology and Utopia to Phillip Wegner’s recent (2002, 2010) work on utopian narratives in the 21st century. Perhaps then, it is easiest to identify spatial study in this paper as the textual interrogation of space, and utopian study as a combined in-text/metatextual concern, especially as it affects the production contexts and creators of these films.

In this context, the abstract appearance of utopian studies and spatiality gives way to much more practical local and textual analyses, and for the purposes of this paper they suit well the dynamic, wonderful and deeply spatial films of Studio Ghibli. The majority of feature films produced by the Japanese animation house provide wholly unique and valuable insights into various arenas of life. This is not an unpopular opinion, and is reflected in the existing scholarship of Ghibli’s catalogue. Amidst a mountain of work can be found explorations of Ghibli’s long history of female protagonists and “blindness to gender” (Iles, 2005); Ghibli as a cultural bridge between Japanese anime and American animation (Hernández-Pérez, 2016); Ghibli as a case study of marketing and audience reception domestically and abroad (Denison, 2007); Ghibli as arguments for pacifism (Akimoto, 2013 & Schipperges, 2018); environmentalism (Le Blanc and Odell, 2019); feminism (Kono, 2017); flight and aerospace (Amzad-Hossain and Fu, 2014); and so on. My concern is primarily for its physical representation of these “worlds,” and particularly as they represent and depict society — entering into the space of “social dreams,” as a utopian premise.

The question, then is not of Ghibli’s relevance to Western media scholarship, but the argument of spatial and utopian dimensions in its work. ‘Utopia’ is a deeply loaded, politicised term, but I would argue that it is not necessarily the case that Ghibli is advocating political interests. Although utopia is political and these spaces are quite often political, the presence of politics does not necessarily render a text categorically “political”. I think the films represented in this thesis advocate dimensions of the dreams of their creators (who, in the subsequent chapters are Hayao Miyazaki2 and Isao Takahata), and although these dreams are bound to these directors and their environments, they also invoke emotional and personal spaces too. This multidimensionality is part of the depth that characterises the studio’s work, and so I would caution the presence of a utopian framework as an indictment of these films as fundamentally political.

Social Dreams and Imagined Communities #

Space. The continual becoming: invisible fountain from which all rhythms must flow and to which they must pass. Beyond time or infinity.

— Frank Lloyd Wright 3

Although what constitutes a ‘utopia’ is applied more broadly in utopian frameworks than in popular imagination, the basic premise is the same — utopias are imaginary worlds that reflect some part of a worldview, inspired by contemporaneous circumstances. They can be good places, called eutopia, or bad places, known as dystopia, but at their core they are grounded in the perspective of their creator (Sargent, 1994). A utopian framework, as it applies to Ghibli, seeks out these perspectives through textual analysis, and by situating statements and published opinions of the creator against their texts. This allows a better understanding of these films among their contemporary cinema landscape, and helps situate them not just as stories but as texts in themselves historically. Utopian frameworks illustrate new dimensions to placing and understanding individual moments and scenes in films, as well as clarify the context and history of a work in broader analysis of its genre.

Whereas utopian frameworks examine texts as objects of context, literary spatiality is concerned primarily with how space and landscape are depicted on a functional level (Tally, 2013). In Ghibli’s case, space is often depicted through detailed watercolour background plates, and the study of spatiality scales cleanly here between individual shots, scenes and broader conceptual linkages of space and time. These spaces hold specific cultural implications, as well as contribute to narratives through the automatic transcendental ‘cartography’ audiences produce as they navigate a fictional world.

Ghibli’s house style for background art is painterly, saturated, and consistently detailed. This lends to a beautified landscape that, through the talent of the artist, renders even the most dismal, industrial backgrounds in a warm picturesque light. It is easy to imagine how this phenomenon has implications for space, and with space arrive questions of cartography, or how space is mapped in the mind (Tally 2013, p. 2). Indeed, the idea of a ‘map’ is a good analogy for the way in which our minds process space in imaginary worlds in linear narratives. Spatiotemporality exists on a foundational level beneath abstracted narrative textual ideas, and is alive in its relationships to other spaces and the order in which they’re presented. This ‘spatial turn,’ as it’s often called (Warf and Arias, 2008), allows us to examine landscape not just as coded cultural vessels in themselves (as products of culture), but as stories in themselves, through their arrangement and depiction in texts.

An Argument for Spatiality #

To apply this in a tangible cultural space, we can look to Kojin Karatani, the multidisciplinary Japanese scholar minimised here as a literary critic, who interrogated epistemically this ‘spatial turn’ in his seminal 1996 book Origins of Modern Japanese Literature. His work provided a foundation for the epistemological births of various ‘landscapes’ in the chaotic Meiji period, during which Japan rapidly Westernised in the mid-19th century. Karatani documents exhaustively the origins of new literary artefacts that usurped and obscured prior Japanese cultural institutions, including depictions of Landscape, the discovery of Interiority, the discovery of the Child, and so on. These concepts in themselves constitute spaces; landscape through its obvious physicality, interiority through its private subjectivity, and the Child through its relationship with cultural assumptions of life-stages and life-spans. It is precisely this work that informs the titles of each section in this thesis, loosely grouping disparate films together against their relevance to these cultural vessels. More critically, Karatani observes the introduction if these concepts as a profound and irreversible shift in the way stories were told, as placeless pictographic poetry was abandoned for the modern novel (pp.45-53) and nature was, for the first time, described in terms of literalist, real physical place rather than transcendental terms (pp.19-26). This is the “discovery” of Landscape — a word that here describes not the ability to see place but the emergence of real place as a distinct, alien other. In other words, Japan’s great ‘spatial turn’.

Within the concern of this thesis then, these valuable textual signifiers are used in a broader argument for Ghibli’s overall relevance as an animation house of “great cinematic spaces.” This will be accomplished in a somewhat multidisciplinary approach involving both the aforementioned utopian and spatial frameworks, and will move vertically between traditional textual analysis and broader efforts at recognising and categorising generic trends and leitmotifs within the Ghibli catalogue, and their distinguishing spatial qualities as cultural vessels. This necessarily recalls a transnational paradigm, at least partially, since (like much of English-language Ghibli scholarship) the ‘universal nostalgia’ described here and in the title of this paper is founded in my own experiences with these films in a Western cultural context. It is only appropriate then that care is given to situate these films historically and in the contexts of their filmmakers, in the tradition of both frameworks outlined so far.

More specific to the aim of this thesis in establishing the spatial value of Ghibli films, no film will be invoked as a single example of all elements of exceptional spatial filmmaking; instead, what I observe to be the most valuable elements of each text will be applied to a multitextual, straightforward argument for Ghibli’s recognition overall. This contributes to the primary concern of this thesis: how has Studio Ghibli employed and represented space, and what components of Ghibli’s spatiality contributes to its importance in ongoing analysis into animation?

To assist, a broad sample of films from across the studio’s history have been conscripted here, from all corners of the studio’s social temperament. Released between 1988 and 2001, there are both older and newer Ghibli films than are depicted here, and the selection is not comprehensive of all directors to have produced works in the studio. Instead, the following films have been selected for their memorable use of space — their ‘immersive spatiality’. For the purposes of this essay, spatiality also invokes the temporal dimension — acknowledging the fluid back-and-forth between physical space and history, both of which form critical aspects of a broader utopian dialectic. Much as utopias are products of their times, the films of Studio Ghibli are found in a similar grounded epistemology, drawing genre and landscape from real-world spatiotemporality.

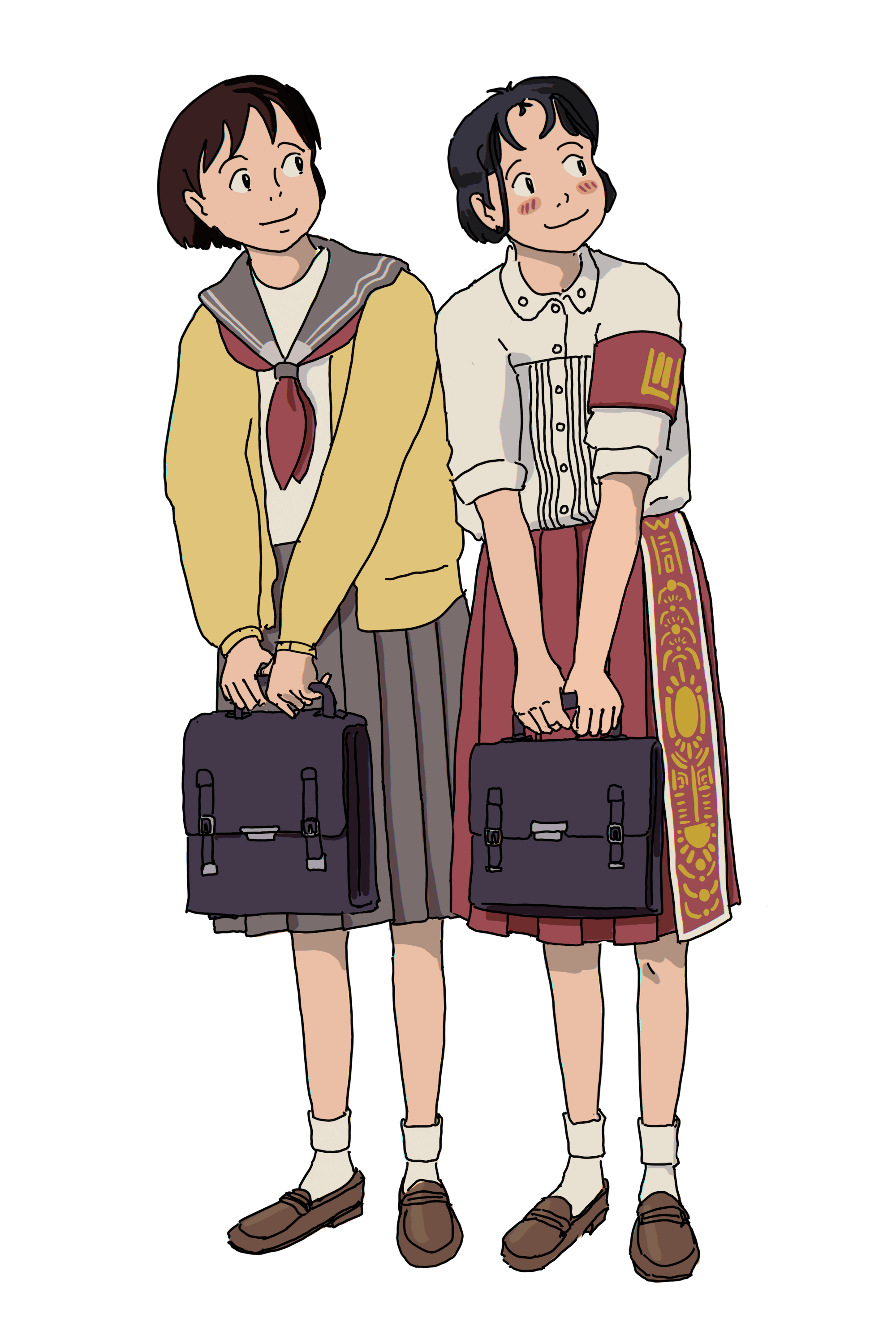

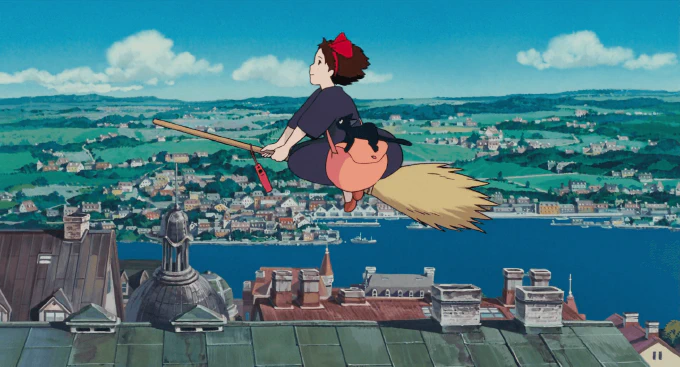

Six films are depicted here, divided into three sections. Section one, Spatiality and Abstraction, introduces key arguments for abstracted landscapes, including the only ‘fantastical’ setting included in this thesis. The first, My Neighbour Totoro (1988), is a wonderful example of utopian instinct — both sentimental and rigorously secular— in its depiction of a pastoral, agrarian community without ‘Landscape’. Using My Neighbour Totoro, this thesis will introduce the groundbreaking multidisciplinary analysis of the aforementioned literary critic Karatani Kojin, and apply his dialectic of the discovery of landscape to interrogate the universal nostalgia of pastoralism and childhood. In a similar fashion, but in a remarkably different setting, there is Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), a charming film about self-discovery as cast against mythical depictions of the universal “European Cityscape,” which is found replicated time and time again in Japanese depictions of so-called Old Europe. Breaking new ground, this study will look to source and identify the physicality of Kiki’s world, and document how it contributes to a utopia as “alternate history”. This effort will draw upon the work of Susan Napier and her seminal work The Fantastic in Modern Japanese literature, employing its scholarship as a historical framework in which to situate Kiki’s deeply historical world.

The next section concerns itself with Interiority and Reproduction, and argues for people-as-utopias insofar as characters can transcend and consequently come to determine places and times. This is not to simply suggest that people can also be landscapes — rather that, within the medium of film, there is a relationship between characters and their landscapes, much as there is a relationship between the watercolour background and the animated cell, and this relationship produces a dialogue that affects the other. So it is, that in Takahata’s masterpiece Only Yesterday, that these boundaries are transcended through memory and interiority. This calls upon again Karatani’s own work (1993) into the emergence of interiority in Japanese literature, and produces a novel framework for the analysis of this film. In Only Yesterday, spatiotemporality is deplatformed from literalism to provide a visual representation of memory and emotion, incorporating the bittersweet, tragic, humorous and absurd in a nonchronological sequence of memories telling a deeply personal story. It introduces the audience to the height of Shōwa postwar affluence in urban Tokyo — the epoch of economic expansion and the Shinkansen — and later contrasts this against the timeless agrarian communities of Yamagata in Northern Japan. Ghibli is well-documented for its positive depictions of nature, and its thematic overtones about landscape and stewardship are well represented by Only Yesterday here. To this end, Yoriko Moichi’s work on Japanese utopian literature helps us navigate these particular and specific dimensions of modern Japanese history, and introduces us to the fantastical as an element of Japanese utopianism.

Next, The Wind Rises (2013) is a quasi-biographical account of aircraft designer Jiro Horikoshi leading up to and during the Second World War. This is the first of two films in this thesis to be set during the war, which devastated Japan and saw a culmination of the radical, dramatic shift in Japanese culture and politics that started in the Meiji restoration. In common use of utopia, a fascist colonial metropole seems hardly appropriate — and yet, as a form of social dreaming, The Wind Rises succeeds. There are eutopias depicted in this otherwise dystopian filmscape — Horikoshi’s employment at the Mitsubishi plant, the hotel in the mountains, the home of his employer — all exist as signifiers of social refuge, and extraordinary spaces amidst extraordinary times. This fits well within the metaphor of a textual analysis of the film itself — in which beautiful things cost terribly, and that impermanence and tragedy do not devalue them. These are places that simply do not exist in modern consumer society, as argued in this chapter — and to that end, they demonstrate the lateral freedoms of social dreaming as a foundation of utopian studies, orthodox to Lyman Sargent’s work on utopian taxonomies.

Finally, Ghibli’s generic trends of childhood and whimsy are recalled in the next section — Childhood and Historicism, in which we return to specific places and times to explore Japan as depicted by Ghibli. Whisper of the Heart (1995), the final film of longtime Ghibli creative Kondō Yoshifumi, depicts a blossoming romance in Tama Hills, and explicitly replicates several real-world landmarks. These are profoundly Japanese spaces — filled with postwar concrete high schools, apartment lifestyles, shrines, trains, and the terraced concrete hills of West Tokyo. Calling upon Phillip Wegner, these spaces and — unusually among Ghibli’s catalogue — the contemporaneous setting, raise interesting questions about the inversion of what Robert Tally calls spatiotemporality. Universal markers of childhood — young love, music, and self-doubt — are cast against Japanese spaces at the height of the Japanese bubble economy. The tension between universality and provinciality in space — depicted here as the schisms between real-world Japanese space and Japan-as-fantasy originating in the minds of audiences abroad — is a critical example of the premise of this thesis.

This paper concludes with another depiction of Japan, though far removed from the pleasant domesticity of Tama Hills. We finally approach Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies, placed adjacent to the conclusion of this paper for its synthesis of the twin concerns that drive this exploration — namely spatiality as social dreaming, and the contextual dimensions of space within transnational products. Grave of the Fireflies is a wartime tragedy, released simultaneously (and not coincidentally) alongside My Neighbour Totoro. If the works depicted in this essay have trended chronologically towards the ‘real,’ then the fact that Grave of the Fireflies adapts an autobiographical story of two children in the poverty of wartime Japan should push the utopian dialectic nurtured throughout this thesis to its breaking point — landscape, interiority, universality, and memory are all being recalled here. It is perhaps Grave of the Fireflies that best exemplifies the tension between utopias and utopias-by-appropriation — and raises questions regarding the depiction of suffering in specific places and times, and the enduring nature of this story across decades and borders. Does the fact that Grave of the Fireflies depicts Japanese civilians — a population uncommon in the war films of former Allied countries — affect its universality and interpretation abroad? If so — what does it owe to that context, and how does spatiality inform its story

From this summary of films, we can already see the trends and leitmotifs that characterise the work of the Japanese animation house. But there are interesting omissions of note, too — particularly that, aside from Kiki’s Delivery Service, these films are established to have concrete real-world locations, and, in the case of Whisper of the Heart, this thesis will visit these. Overall, this list constitutes much of Ghibli’s sober, less fantastical fair, hinged closely to moments and places that are either well-known or characterise aspects of Japanese history and contemporary landscape. This is, to some extent, a necessity while employing utopian and spatial frameworks, which are closely linked to the contexts of places and times. In other ways, however, this list characterises a broad sample of narratives and tones, from the placeless whimsical to historical war-drama, and will showcase well the breadth and depth of the total sum of films produced by the studio.

In summary, we can see in this introduction the foundations of a multidisciplinary analysis, blurring textual analysis and analysis of contexts within well-documented utopian and spatial epistemologies. There is perhaps no better case study in Japanese cinema presently than that of Ghibli’s catalogue, navigating in the rare vertices of artfulness and textual depth with approachability and mainstream success. Spatiality and time; body and interiority; memory and metaphysic — these are the foundations of social dreaming, and within the rich visuality of the animated medium, in which all frames and shots are designed and nothing is simply a “background,” utopian spatiality provides an excellent foundation upon which to explore these films.

Spatiality and Abstraction #

Landscape in Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro #

If there is a single film of concern in this thesis that demonstrates a utopian, spatial dialectic within the films of Studio Ghibli, it is here, in 1988’s My Neighbour Totoro. The film showcases the dislocation of space common in Miyazaki’s work, and indicates at face value a landscape that transcends Miyazaki’s own lifetime as a sort of cross-generation nostalgia. So there is this contradiction, as is common in Miyazaki’s great stories, between progress and the past. This idea probably does not strike the reader as particularly novel — environmentalism and balance is an obvious theme common throughout the broader Ghibli catalogue — but “progress” and “conservation” here are not situated in the context of the film’s release, nor are they broader gestures at grand ideas about the future and past. Rather, they are symptoms of the tension between ‘old ways,’ characterised by social community, locality and land dependence, and a plastic, uncertain modernity. Miyazaki describes My Neighbour Totoro as taking place in 1955, or thereabouts, but acknowledges that “what [the production staff] had in mind was a ‘recent past’ that everyone could relate to” (VIZ, 2005). He reinforces this point by describing his deliberate exclusion of personal nostalgia during the film in his semiautobiographical work Starting Point (2009, p. 355). In another interview, Miyazaki remarked:

“A lot of people now are nostalgic for Japan as it was in the Showa ’30s, but it was actually an unhappy period for me. Why? I was frustrated because nature — the mountains and rivers — was being destroyed in the name of economic progress.” (Schilling, 2008).

In the Japanese calendar, 1955 is the 30th year of Shōwa, placing it in the height of a period broadly characterised by rapid economic development and construction after the Second World War. Of course, My Neighbour Totoro depicts a space far removed from the noisy urbanism rapidly developing in Japanese cities — at odds with and even disrupting preconceptions of modernist progress. This submersion of capital-M Modernity is present throughout the film. In his seminal analysis of modernist instinct, Marshall Berman illustrated a vision of modern living remarkably hostile to the landscape of Totoro, arguing that 20th-century society “speeds up the whole tempo of life,” and severs “millions of people from their ancestral habitats, hurtling them half-way across the world into new lives,” as “rapid and often cataclysmic urban growth; systems of mass communication, dynamic in their development, [envelope] and [bind] together the most diverse people and societies […]” (Berman, 1983, p. 16).

And yet, in Miyazaki’s childhood fantasy, we are presented a place of an excruciatingly agrarian pace of life, no depiction of commerce (and almost no recognition of the existence of money at all), of people dependent on place and history, living and moving into old, run-down homes in which even a telephone is a scarce feature. This depicts a sort of asymmetric timelessness, or, as utopian scholar Phillip Wegner argues, an “alternate history,” in which the priorities of the postwar Japanese state have been totally inverted, and the consumer society that flourished under American occupation and democratisation was never introduced (Wegner, 2010). To use Marx’s phrase borrowed by Berman (1983), Miyazaki is, in some sense, recapturing solidity that, in our own world and in his childhood, had long since melted into air during the Meiji restoration. It is here that lies the distinction of Miyazaki’s place of tension from broader thematic depictions of the future and past, found not in contemporary anguish or conservative retrospection, but in a dislocation of spatiotemporality, building worlds that, while thoroughly Japanese and midcentury, do not really exist. This is not to argue that no such villages in Totoro existed in 1950s Japan — the film was inspired by the Saitama prefecture outside Tokyo — rather, that the textual spatiality of My Neighbour Totoro, per their construction in animation, are pulled from social dreams rather than merely depicted historically. It is by ‘social dreaming’ that this thesis distinguishes utopian instincts from fantasy, and it is by social dreaming that Ghibli’s films are able to reach and engage with the subliminal concepts. It is not the absence of telephones, or the depiction of animism that recalls a utopian spatial dialectic, but the whole inversion of priority that cascades and colours every part of the film.

So, in demonstrating a vision of modern space without modernity, what remains in the film? Depleted of contemporary indicators, My Neighbour Totoro could be taken superficially as a sort of aimless conservatism, capturing the whimsy and nostalgia of the smallness of childhood. After all, it is through the childish lens of the sister protagonists that we see the forests and rice paddies of Totoro, and much of the film is dedicated to chronicling the pleasantly aimless activities of a four-year-old girl. As Wegner (2010) recognised, the “narrative utopia” has radical implications when we look to the deeper, underlying metaphysic that belongs to the ‘dream’. Where overt themes are recognised, internalised and reproduced at a plot level, the way spatiality operates deep within Totoro introduces critical dimensions as to why the film makes such a powerful text for utopian spatiality — specifically, its absence of landscape, childhood, and architecture.

We see here a dialectic introduced by literary critic and philosopher Karatani Kojin, and applied by Wegner (2010) in the case of Totoro. Karatani argues that, prior to the introduction of Western culture to Japanese art during the 19th century, the landscape metaphysic as we understand today did not exist (Karatani, 1998). This is, in effect, demythologising Western preconceptions about nature as an “other;” returning a foreign, transcendental space to the physical world. Modern Japanese literature, Karatani argues, is inundated with such constructions — and by their nature, these “epistemological constellations” suppress their own origins, appearing as immutable objects; an undeniable physical fact. What Wegner argues for, and this thesis incorporates as a Japanese-utopian framework, is the ways in which Totoro and more broadly, Studio Ghibli, suppress such constructions, and how they reemerge abroad as global, transnational fantasy, since I argue that fantasy cannot exist without landscape.

In real terms, what do these constructions mean for the film? In terms of spatiality, My Neighbour Totoro is suspended in a sort of abstraction, pleasantly liberated from naturalistic, realist depictions of the world common to live-action cinema. As American film critic Roger Ebert described of another Ghibli film, Grave of the Fireflies:

“The characters are typical of much modern Japanese animation, with their enormous eyes, childlike bodies and features of great plasticity (mouths are tiny when closed, but enormous when opened in a child’s cry — we even see Setsuko’s tonsils). This film proves, if it needs proving, that animation produces emotional effects not by reproducing reality, but by heightening and simplifying it, so that many of the sequences are about ideas, not experiences.” (Ebert, 2000.)

In this spirit, we can see Totoro’s suppression of literalist instincts for a sort of demonstrated, if not depicted, reality that absolves the schisms between place and person. There is much work in media criticism with the goal of teasing out buried Shinto iconography and situating My Neighbour Totoro in its cultural and historical context. This, I fear, suppresses the rich ambiguity and abstraction animation affords the film — of course, the shrines depicted in the film belong to Shinto practices, and of course, the rice paddies, local railway and cultural behaviours are distinctly Japanese — but within the pretext of Totoro as a ‘dream,’ or “what-if,” as Wegner calls it, these images are reintroduced as new, if thoroughly Japanese-oriented, artefacts. Shinto is stripped of its historical and nationalistic implications and is reintroduced as a vessel for animism and a respect for all objects. Landscape is abolished and place is returned as a physical entity, standing once again only in its immediate physicality and utility. Even the child — another one of Karatani’s constructions — is reintroduced here with ageless burdens and complexities; in other words, a small, growing adult, far removed from the objectifying cultural force of modern education systems and children-as-consumers.

And so there is a tension here — perhaps, even a proud contradiction — that exemplifies the richness of spirit in Miyazaki’s work. On one hand, there is the film’s undeniable contexts, founded deep in Miyazaki’s personal and political stories, and there is also the film’s wonderful demolition of such matters in place of a fictional, if Japanese, universality; a transnational appeal that sees this film delighting people across the world. That audience scalability, between local, regional and international viewing, is a recurring feature of Ghibli’s catalogue, and testifies to the underlying spatial and utopian vision’s widespread appeal.

‘Old Europe’ and prewar nostalgia in Kiki’s Delivery Service #

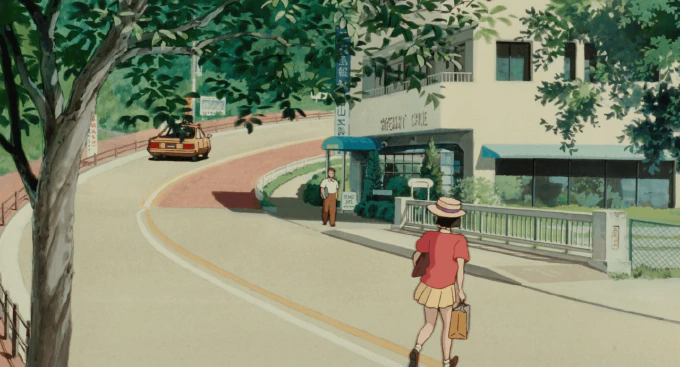

Using My Neighbour Totoro as a metric for spatiotemporal discussion in Ghibli, the next film arranged here marks a shift from the overt spatial questions of heavy concerns in literary history and metaphysics, towards the world of temporality, witchy semiotics and the delight of domestic fantasy. Kiki’s Delivery Service, released a year after Totoro in 1989, is one of Ghibli’s ‘European adventures,’ a legacy traced all the way back to Miyazaki’s early work on Heidi, a Girl of the Alps in the 1970s (Le Blanc & Odell 2019, p. 29). In many ways, it is a suitable film to elaborate and build upon the concepts discussed in the previous section, for Kiki’s Delivery Service, like My Neighbour Totoro, is quite easily characterised as the same alt-history “what-if” paradigm, displaced and rebuilt in a fictional European setting. Kiki, a young witch leaving home for the first time to develop her powers, finds her enemies not to be evil wizards of ancient evils, but self-doubt, money and loneliness. This marks what should be considered a critical shift in this ‘witch story’; its introduction to a domestic, personal space that appeals to both emotional narratives of development and self-discovery, and the petty fantasy of ‘small magic’ in an otherwise ordinary setting. Kiki does not wield tremendous magic power capable of altering history, either local or worldly — she accomplishes that instead through her character and relationships.

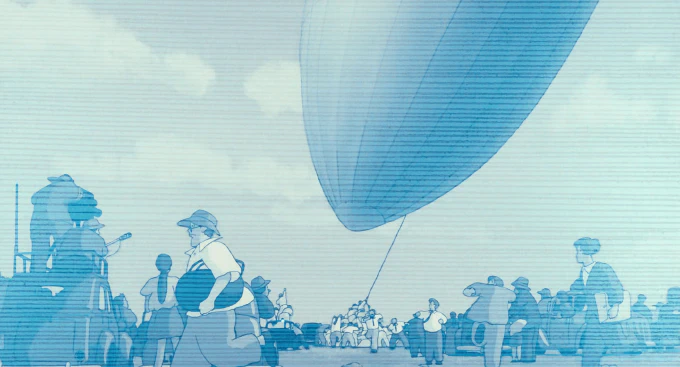

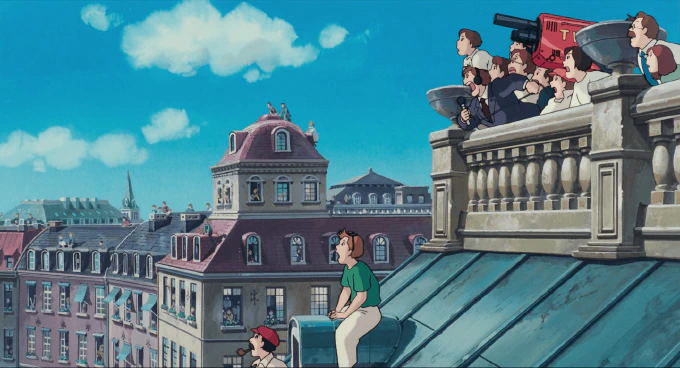

The film is set in the placeless town of Koriko, a 20th century coastal city in European fashion. As per the abstract wonder of animation, little is told and much is shown about life in this place. Agrarian quiet in My Neighbour Totoro is inverted here in a sort of fictitious European fantasy; a bustling seaside city of cafés, boutiques and, most importantly, bakeries. This is further illustrated in the context of Ghibli’s familiar utopian leitmotifs, as wonders of the golden age of air travel (the dirigible Spirit of Freedom) coexist with distinctly postwar artefacts in fashion, technology and teen-age culture. In the same sense that My Neighbour Totoro glimpses a vision of midcentury Japan in which the Meiji restoration might have never occurred, Koriko is a delightful European landscape in which it appears the Second World War never happened. This is remarked upon by Mio Bryce in a broader examination of Kiki’s depiction, describing Koriko as exhibiting a “strong sense of retrospection and other-worldness” (Bryce 2006). It is not that Koriko is entirely foreign — by most accounts, a young female witch in a European city should be superficially familiar to most Westerners — but that instead Bryce recognises that the dichotomous relationship between Japan’s (post-Meiji) introduction to ‘witch stories’ and the Western, Christian tradition of witch lore, and that the resulting product disarms Western presuppositions about European witches through its emphasis on “transition,” rather than “training”. Kiki does not attend a school for witchcraft, or takes on mentorship, as Bryce notes (p. 43), but rather participates in a feminised tradition of self-discovery and place.

This results in a film in which, much like Totoro, Miyazaki’s masterful, amorphous storytelling cautions ambitious attempts to trace textual lineage to Japanese “predisposition” or storytelling tradition. Susan Napier’s landmark work, Anime: From Akira to Princess Mononoke, notes as much:

“The idea of a girl leaving home and setting up her own business would be surprising in any culture but particularly so in Japan. In Kiki’s happy independence we see Miyazaki’s technique of defamiliarisation working most effectively. Traits that might have been taken for granted had the protagonist been a boy—autonomy, competence, and ability to plan—are freshly highlighted through Kiki’s femininity to create a memorable coming-of-age story.” (Napier 2001, pp. 132-133).

It is precisely this process of defamiliarsation — through obfuscation of place, time and culture — that allows Kiki’s Delivery Service to play in service of its story and its spaces. Relevant to spatiality, the coastal city of Koriko is part of a recurring interest (and quite possibly, a fascination) on the part of Miyazaki for a mythologised ‘old Europe’. This point was made by Chris Wood, who described Ghibli’s Europe in Porco Rosso as an object of a “tourist’s gaze,” and argued for such depictions to be understood as part of longtime Japanese wonder and apprehension towards the European powers (Wood 2008, pp.114-120).

Nonetheless, although Kiki’s Delivery Service depicts a much broader and typically complicated society than My Neighbour Totoro, it is less political overall. That it is not to say the film is apolitical, or lacking in textual complexity — I would argue that all of Miyazaki’s films are deeply political, and characterise a moral and structural richness that is unsurpassed in contemporary anime. It is simply that, in the case of Kiki’s Delivery Service, the questions asked of this ‘alternate vision of history’ are different to the interrogative, structural dialectic within My Neighbour Totoro. Where Totoro challenges foundational assumptions about Japanese historicism, affluence, technology and modernity, Kiki’s Koriko is a wholly more fantastical glimpse into a blossoming, affluent Euro-themed society left intact in a depiction that recalls William Morris’s “Epoch of Rest”. In both cases, acknowledging these film spaces are extrapolated from our own global history — the Second World War looms large. Emerging like a phantom, it raises questions about artefacts that appear in these films that otherwise were radically altered by the turbulence of the early 20th century. In Totoro, it is agrarian pastoralism in a pre-Shōwa society. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, it is the splendour of a zeppelin, the romantic mythos of romantic European society, and the sanctity of technology as a servant of peacetime.

A.J. Rocca argues for Koriko as a foundation for the climax of the film — a resounding ‘what-if’ rejection of the “ghost of modernity”:

“[In Koriko] food and goods are plentiful, there’s no trace of any deep social antagonisms, and new technologies like the Zeppelin and biplane are presented as whimsical machines full of novelty and wonder as opposed to weapons of war. Koriko is nothing less than a utopia, and more: it’s a modern utopia; an idealised picture of what the 20th century might have looked like in the dreams of a Bellamy or a Chernyshevsky.” (A.J. Rocca, 2017)

The film guides the setting into the same climax it does its protagonist, Kiki. As Kiki discards self-doubt and reacquires her agency as a witch to save her friend, Tombo, a whole pre-war era is backed into that moment and held hostage. Rocca notes that, as the dirigible is wrested from human control, a reporter exclaims phrases pulled from the real-world Hindenburg disaster. It is in this moment, followed by the conclusion of the film in which no-one was hurt, that Kiki’s Delivery Service marks a fantastical departure from our own timeline — one that would, after the Hindenburg disaster, result in the bloodshed of the Second World War, and the iron curtain, depression and austerity that followed it. Out of Ghibli’s catalogue, Koriko is perhaps the most explicitly visionary in its depiction of alternate and parallel timelines

Consolidating the spatial turn of both Totoro and Kiki, linked in this argument by their mutual depictions of ‘lost pasts,’ is the universalising power of reigning in the ‘fantastical’ (i.e. witches and forest spirits) with utopian thinking, drawn from the real world. This fascination with the interplay of the fantastic and the mundane extends well beyond the story of our girl protagonists — it is reproduced throughout these worlds, colliding their real-world contexts with nostalgic whimsy resurrected by proxy through the studio’s more fantastic elements — forest trolls and flying broomsticks. This is how a village amidst Japan’s great economic miracle, a time dominated by urbanisation, deforestation and consumerism, is resurrected in My Neighbour Totoro as a sort of utopian ‘no-place,’ colliding pre-Meiji intuition (Karatani 1993) with telephones and trolley cars. Similarly, this is how a European seaside town, fresh out of the First World War and awaiting a brutal resurgence of violence in the ‘Age of Frustration4,’ is resurrected in Kiki’s Delivery Service as a tranquil old-world theatre of European architecture, home to zeppelins and witches alike. Alternative histories are not simply spaces of the past, but in fact vessels of the present recreated elsewhere; displaced and transcendent. That is how Studio Ghibli reproduces conventional space in a utopian fashion.

Interiority and Reproduction #

Memory and Agrarianism in Only Yesterday #

There is perhaps no finer testament to the specialness of the films of Studio Ghibli and Isao Takahata than 1991’s Only Yesterday. It is a film unique in the landscape of animated cinema. It is a sensitive depiction of womanhood in Japanese society, filled with muddy emotion and bittersweet moods usually reserved for live action feature films. Only Yesterday is strikingly empathetic and restrained in its representation of all parts of protagonist Taeko’s life. The people of her memories are complex, and her recollections of childhood are joyful, curious, mundane and occasionally heartbreaking. This is a film that could not exist in the mainstream animation culture of the U.S., but in Japan it was the highest-grossing domestic film of 1991. A film that typifies of Takahata’s experimental oeuvre, Only Yesterday forces the casual viewer to reassess assumptions about what sort of stories animation is able to tell. It is delicate, contemplative and nostalgic in a medium dominated by films that are usually exhilarating, fantastic and whimsical. This approach creates unique landscapes previously undiscussed in Ghibli’s cinema catalogue, and so argument for their relevance will be made here. This includes multidimensional spaces that are included in the themes of the film as well as more literally in Takahata’s approach to filmmaking itself. There obvious contrasts in the film — between agrarian and urban living, and memory and the present, each of which develop their own rich spaces. Takahata’s pioneering approach towards the actual mechanisms of Japanese animation push this analysis further, however — and we’ll have a look at the creative ways he illustrates these worlds.

Only Yesterday introduces Tokyo office worker Taeko, a woman in her late twenties about to embark for the countryside, where she explains to a friend that she’ll “visit family,” — in reality, though a tenuous familial connection exists, Taeko uses her time in the rural countryside to get away from city life and participate in the safflower harvests in Yamagata. On the train ride there, she finds herself surrounded by memories of childhood. After her arrival in Yamagata, she is picked up by a second cousin of an in-law, Toshio, with whom she is barely acquainted. Her displacement and sudden nostalgia allow bitter questions to emerge — at 27 years old, has Taeko been true to the dreams of her 10-year-old self? What would her childhood self think of her now? As she participates in rural life, and learns more about Toshio, the film pirouettes between self-contained scenes and images of her childhood and the present, sometimes contrasting them, sometimes merely observing a memory. A tapestry of topics — travel, school, puberty, menstruation, puppy love, family and dreams are recalled in lyrical glimpses of the past, some of which caused distributors to regard the film as “undubbable” (i.e., redistribute the film with the characters speaking English, performed by an English cast). Producer Geoffrey Wexler observed:

“When I joined Ghibli and I talked to them I said, “Are you guys ever going to release this?” and they said, “We can’t release it.” I said, “Can it have it back then?” and they said, ”Yes.” I think the discussion of the girls having their periods may have been a problem. A lot of people squirm about that in North America, but in other countries they don’t. It wasn’t a problem in some countries. I think also the pacing was hard for North America” (Aguilar, 2016).

These memories, broadly depicting different aspects of childhood (or, for that matter, linear), offer a unique unsentimental glimpse of middle-class girlhood in postwar Japan. It is only appropriate that these memories resurface during Taeko’s own physical displacement, since the transition between her urban and agrarian identities offer ample room for dislocated reflection in the spaces between. They reflect what could be described as an ‘abstract temporality’ in the absence of mapped space — it is here that we see linear chronology in the film begin to break down, as does the world beyond, and for a moment the past and present intermingle freely in the train carriage. New places have us recalling and relying on a dialogue with past memory and the future. On a slow-moving sleeper train into Japan’s mountainous interior, having left city life behind and having not yet arrived at her destination, Taeko experiences this dislocation of time, and so memories of her youth emerge uncontrollably throughout the film. It is not simply that Taeko is daydreaming deliberately — in several scenes, a memory bursts into her consciousness, triggered by spaces around her. It is a powerful depiction of how emotion and memory is bound to places, shapes, and images, and how those things can reemerge in their depiction.

Only Yesterday is a film about the ‘spaces between,’ formed in a collision of landscapes. Memory is perhaps at the heart of the spatial concerns of the film. The Japanese title, Memories Come Tumbling Down (Omoide Poro Poro) is perhaps a better summation of the events of the film, since the themes of the work and Takahata’s filmmaking rely so heavily on the interplay between past and present here. They are visually distinguished through changes in style of both backgrounds and character cels. When Taeko recalls a moment from her childhood, Takahata strips our sense of place right back. What follows is a beautiful representation of the foreignness and inaccessibility of childhood memories, depicted masterfully in gentle watercolour strokes and liquid shapes. These scenes look almost like traditional Japanese paintings, employing artful negative space and desaturated tones to direct attention and emphasise detail. The environment of Taeko’s childhood looks almost half-finished, invoking the haze of memory and her bias towards her own presence. It is not merely a depiction of absence, but is used to emphasise the vitality of the memory, by depicting honestly the events as Taeko remembers them.

More subtle, however, is Takahata’s unusual shift in the style of characters themselves. In the scenes of the present day, features of the face like cheeks and smile lines are animated in a noticeable and sharp break from anime’s tradition of simplification. In childhood, however, these illustrations disappear, where wide, plastic faces conform to Ghibli’s established style. This is both an artefact of Takahata’s experimentation with animating around prerecorded lines (a practice unusual for anime, where actors usually perform after production is underway), and a stylistic distinction that emphasises the schism between Taeko’s nostalgic Shoujo world and the real ‘present’ (Campbell, 2020). This is surely deliberate, since young Taeko represents well the common features of Ghibli heroines, regarded in Japan as ‘Shoujo’, literally ‘young lady’ or ‘little girl’. This characterisation, described by Tamae Prindle (1998) as a “lacuna between adulthood and childhood, power and powerlessness, awareness and innocence as well as masculinity and femininity” is a common trope, but although commonly depicted across Ghibli’s catalogue it alone does not fully summate the depth and complexities of their protagonists. Young Taeko reflects the shoujo idea specifically in a scene in which she dreams of becoming an actress — in the memory, her eyes are larger and exaggerated in typical shoujo manga style, in her mind “acting out” the exaggerated beauty and proportions of the shoujo trope. In this sense, there is a clear spatial distinction between the naturalistic styles and illustration of the present and the malleability of dreams and their abstract temporality.

The division of landscapes is not unique to the mechanics of cinema, however — Only Yesterday has sincere thematic spaces also. By this point in the argument of this thesis, Ghibli’s interest and dialogue with natural landscape and the environment is well established. Unlike the functional and artistic implications of space, the ‘worlds’ of Only Yesterday do not invoke specific personal memory but broader historical contexts, largely informed by the social upheaval and rapid introduction of consumer society in the Shōwa period, albeit through a very different lens than that of My Neighbour Totoro. We see the introduction of nostalgia as informed by commodity-objects, including references to period-appropriate music groups and television. The inclusion of the series-0 Shinkansen, Japan’s first high-speed rail network, is symbolic of the postwar era, as a culmination of Japanese industrial strength and war recovery. Despite the film’s initial release in 1991, the story is set in the early 1980s, positioning Taeko as a child in the height of the baby boom and inextricably positioning her as a girl of Shōwa. This acknowledgement is important, because it finds Taeko’s fascination and eventual adoption of an agrarian lifestyle uniquely within this historical Japanese period, and characterises her personal struggles against deeply cultural spaces. This functions alongside the playful past-present mechanic, widening the cultural and technical gap between childhood and adulthood. On the overnight train trip out of Tokyo, Taeko sees little of the passing landscape and the audience experiences a dislocation of space, unable to map the journey without prior knowledge of her destination. In this sense, Shōwa Tokyo is not just a memory but a physically alien world, segregated from her rural destination by an inscrutable journey between. Her childhood memory, and its legacy in Japan’s vicious urbanism, is divorced from the present twofold, and an inversion of topos has occurred. The film shows little of present-day Tokyo, because there is little to tell — to a Japanese audience in the 1990s, this constituted a ‘default’ space.

The same cannot be said for the depiction of Yamagata, and Taeko’s retreat to the country marks a visual departure as dramatic as that between the memory scenes and present Tokyo. Despite her stay in a thoroughly Japanese farmhouse amidst steep, terraced hills, European elements also emerge. Toshio, her acquaintance and friend, mentions an affection for traditional Eastern European music, and agriculture in the region is dependent on the harvesting of Saffron flowers, an originally mediterranean crop. This reflects, to some extent, the minor Japanese interest in ‘Old Europe,’ but also helps distinguish Taeko’s journey as somewhat special across Japanese agriculture, distinguish the practice and technique of Saffron harvest against staple crops like rice. We see every part of the plant being used, using its valuable threads to dye clothes. Here, Taeko is obviously an outsider — despite her eagerness to learn and participate — and so her Shōwa nostalgia, which she confesses to Toshio, is unreciprocated. This ties into a broader, studio-wide thematic interest here towards the deficiencies of Japanese urbanism. Most obviously, the previous chapter’s My Neighbour Totoro celebrates agrarian living, and it is not unreasonable to associate Only Yesterday with this general post-Shōwa urban skepticism. The film makes obvious, however, that Taeko’s tentative agrarian retreat is presented as an alternative, rather than default space. It is very much a human domain, just distant from the bustling heart of Tokyo, which is epistemically opposed to Totoro’s more foundational absence of landscape.

Here we return to Karatani, who articulates the origins of this schism of conception:

“Of course, I do not mean to say that landscapes and faces had not previously existed. But for them to be seen as “simply landscape” or “simply face” required, not a perceptual transformation, but an inversion of that topos which had privileged the conception landscape or face” (Karatani 1993, p. 56).

In other words, it is precisely this conception of rural life that has alienated it, and so despite the similar Ghibli watercolour background style, they are totally different conceptions of ‘agrarian living’. Miyazaki has said as much while discussing the Japanese relationship with nature:

“The biggest reason why mountain animals decreased so much is agriculture. It’s human arrogance to say that the country scenery is beautiful. A farm basically takes away the chance to grow from other plants. It’s more like barren land. The productivity of wasteland is higher than that of farmland. It’s the same for other creatures. It’s because of the time (we live in today) is such that I have to even think such things” (Miyazaki, 1997).

In the context of this essay’s total argument, then, we see Only Yesterday advocate Ghibli’s spaces in two places — first in memory, in the dichotomy of childish abstraction and mature naturalism, and then in physicality, in Ghibli’s environmentalist leitmotifs — expressed commonly as a New Japan/Old Japan anxiety. Only Yesterday, like almost all of Takahata’s films, experiments with the format and style of animation to better express the function and mechanics of thematic or story concern, which marks a departure in the body of this thesis from Miyazaki’s unwavering orthodoxy to the Ghibli “house style”. This affords him a pleasant abstraction, not just in Only Yesterday but across his filmography, that is not usually present in Miyazaki’s more fantastic, but literal, filmmaking. In a paper concerned with spaces and their representation, Takahata takes an artistic wrench to a cohesive characterisation to Ghibli’s spatiality, and films precluded from this argument, including the likes of Pom Poko and My Neighbours the Yamadas might threaten to collapse it entirely, outliers as they are. Only Yesterday, however, and his 1988 film Grave of the Fireflies (which this this paper will look at in the next section) represent novelistic filmmaking that expands the conventions of cinema, and critical to the concern of this essay, the methods in which the studio’s worlds are constructed and depicted.

Childhood and Historicism #

Love and Whimsy in Whisper of the Heart #

Now far from the fantastical images of a ‘lost past’ in Kiki’s Delivery Service and My Neighbour Totoro, we arrive in Whisper of the Heart at the urban heart of Tokyo in the midst of the Japan’s ‘Lost Decade,’ a setting close to home for the contemporaneous Japanese audience that saw it in cinemas in 1995. This section also marks an interesting shift in this paper’s textual analysis, from the imagined to the ‘real’: places that you can ostensibly identify upon a map and — as demonstrated in this chapter — visit for yourselves. In this chapter, we’ll look at Ghibli’s depiction of time and childhood within spaces and dreams, and how they interact and play with the real world

Whisper of the Heart introduces Shizuku, a fourteen-year-old junior high-schooler whose creative ambitions and creeping anxiety about what she wants out of the future have her listless as serious decisions about school and life approach. Her bookish habits spur a meet-cute with a boy in her year who initially annoys her, Seiji. From there, a story unfolds about creativity and self-discovery, positioning Shizuku as a burgeoning creative as her relationship with Seiji blossoms. She navigates the exceptions of herself from within and without, culminating in the draft of her first novel as her school exams loom.

The manga on which the film is based (of the same name) prioritises the relationship between Shizuku, Seiji, and a third fellow student as part of a love triangle common in Shojo manga. In Miyazaki’s hands, however, the film presents Shizuku as an independent spirit, following her heart on a journey of self-confidence and discovery alongside, rather than because of, Seiji. In the context of the severe recession underway in Japan at the time, their creative ambitions are strikingly brave, and describe a circumstance that was undoubtedly relevant to young Japanese contemplating their futures in 1995.

Within the film, however, the asset bubble and stock market crash couldn’t be further away, as a more domestic conflict within a middle-class family plays out. Shizuku’s parents are scholarly (a common trope within Ghibli’s catalogue) — her father works at the local municipal library and her mother studies at university. Since her sister, with whom she shares a room for the first part of the film, is also a university student, Shizuku is a somewhat independent figure. It is possible that her bookishness is inherited at least in part from her parents. Her life is spread across Tama, commuting to and from school and her father’s library, as well as the commercial heart of her hometown. Hills are a characteristic feature of the area, and the film depicts curving roads, vast concrete retaining walls and steep staircases throughout.

Whisper of the Heart makes full use of the Tamagawa suburb in Tokyo, employing locations in all manner of spatial functions. Shizuku finds herself exploring parts of these hills, and we explore with her — where conventional filmmaking intuition would merely cut between locations, Kondō (and also screenwriter Hayao Miyazaki, who drafted the storyboards) use a practice common among Ghibli films in which the journey is presented in part or in full, allowing audiences to map recurring spaces in the film. These are thoroughly immersive journeys, with detailed views into the outside world as they whiz by on trains or on bicycles. Weedy (2018) calls this approach “perceptual modulation,” and recalls Miyazaki’s invocation of Ma as its reason for being, arguing that:

“[…] it is the train-like motion of these animated vehicles that perceptually modulate the viewers. Their gaze is then focused on the character’s simple face, and the combination of these two elements creates this specific empathetic response resulting in characters that feel multidimensional, despite the flat, two-dimensional art style.”

This approach also means most viewers will cultivate a basic understanding of Tamagawa — and by extension, the anchors of Shizuku’s life — through the relationship of these spaces with Shizuku and with each other. This approach also has a dramatic effect on the pacing of the film, which Miyazaki identified above as Ma in an interview with critic Roger Ebert. “Emptiness,” Miyazaki said. “It’s there intentionally” (Ebert, 2002). He proceeds to distinguish it from Makurakotoba, or “pillow words,” found in Japanese poetry, since Ma describes the ‘negative space’ or ‘emptiness’ of a scene, both physically and conceptually. In these contexts, the depiction of a journey — consuming money and time to animate — are clearly important parts of pacing and storytelling and help to provide breathing room between scenes. They also provide a physical dimension between locations, even if their specifics remain vague — we might not know for how long the train runs, or which stations she boards and alights, but we understand that her home and the library are linked together by a short walk and a train trip. This map helps illustrate what should be an abstract, alien series of places by their relationship to each other and Shizuku, reorganising them spatially.

The film is set in and inspired by Tamagawa — centred on the Seiseki Sakuragaoka station on the Keio Line specifically — and many locations depicted in the film are inspired by locations in this area. In this sense, there are two places that appear simultaneously in the film. To those that are familiar with the local area, the film faithfully recreates and depicts the landscape and architecture of Tamagawa, with all its local history — from its origins in the rapid expansion of Tokyo suburbia in the ‘60s, to its Keio line station and commercial surrounds. To those unfamiliar with Tamagawa, these places transcend their real-world origins and become fantasy, drawing more broadly on concepts of ‘life in Japan’. A foreigner may not recognise Shizuku’s Danchi as a postwar public housing initiative common to the Tokyo metro area, but they may very well recognise her apartment lifestyle and the concrete structure’s open-air staircase to be ‘Japanese.’ In this sense, there is a Shizuku of Tamagawa, a Shizuku of Japan, and perhaps even Shizuku of universal adolescence, with the specificity of her environs and circumstance irrelevant to the broader narrative strokes of the film.

In typical Ghibli fashion, there is an obvious presence of this ‘universal Shizuku,’ even within this deeply Japanese film. Most obviously, there is mention of Seiji’s interest in a traditionally European craft (violin making) and his ambitions to study under an expert in Italy. More broadly, however, the recession that devastated Japan’s ‘economic miracle’ during production is replaced by broader gestures towards familial concern and adolescent uncertainty, requiring Shizuku to draw upon confidence in herself and her ability to justify her departure from the “usual path”. She has noble and disarmingly charming literary ambitions in an education system that prioritises test-taking and academic performance, and weighing her dreams against family and society are at the heart of the themes of this film. Shizuku’s parents, while hesitant and concerned for her wellbeing, are supportive of her ambitions and largely defy stern, conservative Japanese stereotyping (Nakayama 2014, pp.17-19), allowing Shizuku’s circumstance to transcend Tamagawa and Japan. These are the “shared cultural codes” described by Frans Mäyrä (2010, p. 38), who recognised Ghibli’s propensity to demonstrate “contemporary global concerns” that are “readily available as a cultural dialectic for the future.”

This is perhaps symbolised best by the film’s use of ‘Country Roads’ by John Denver, which is referenced throughout the film and finally sung during the climax of the film — a concept which, to West Virginians, might seem delightfully absurd. Walter Chaw for Film Freak Central expressed this colourfully, writing in his review:

“The obsession with reworking John Denver’s hilljack schmaltz classic “Country Road” into an un-ironic ode to the “concrete roads” of the picture’s Tokyo-bound little girl protagonist, for instance, almost by itself renders Whisper of the Heart a Hello Kitty! for that particular brand of Japanese, Yank-ophile, cross-eyed badger shit” (Chaw, 2016).

He adds, “[the song] reminds us of how peculiar a beast cultural diffusion can be.”

Perhaps, throughout the Ghibli catalogue, there is no better representation of how wildly different cultural spaces interact and fuse into new immersive experiences — in the same way that Tamagawa for many Westerners is now illustrated by the beautiful watercolours of the film’s backgrounds, perhaps the song ‘Country Roads’ for Japanese audiences in 1995 recalls not American mountains but Japanese hills. This is whimsy at its finest, as a great equaliser — and represents Ghibli’s ability to resonate internationally, even within films of real physical location. And it is precisely in this displacement of location and meaning that Whisper of the Heart reveals the importance of ‘subconscious cartography’ in these worlds, especially in unfamiliar places.

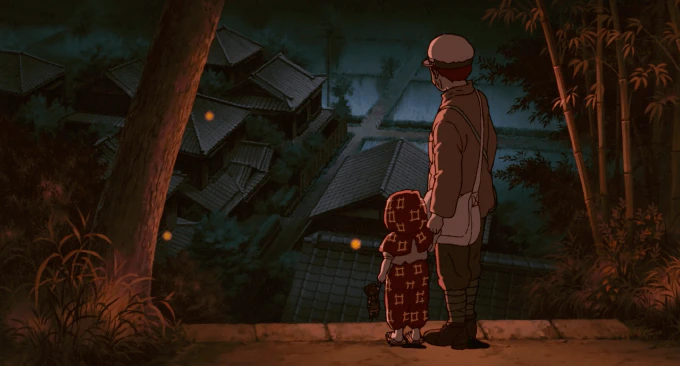

Mortality and Innocence in Grave of the Fireflies #

Grave of the Fireflies originally released in Japan as a double feature, accompanying My Neighbour Totoro to cinemas. At first, this practice may strike someone familiar with both films as totally bizarre — Grave of the Fireflies has been characterised as a Japanese “Schindler’s List” and My Neighbour Totoro is associated most commonly with wholesome, family cinema and came to define Ghibli’s universal nostalgia. In fact, the decision to play them back-to-back urged Phillip Wegner in part to theorise My Neighbour Totoro as an alternate history dream that contrasts the brutal naturalism of Grave of the Fireflies:

“Not only did many of the same animators and production teams work on both films, there are a number of references throughout that suggest it and Totoro were intended to be understood as a complementary pair. For example, the lush visual representation of the countryside that the children inhabit for part of Grave of the Fireflies recalls the setting of Totoro; and at one point, the young protagonist Seita lies to his sister telling her that their mother – who perishes after being severely burned in the attack on their city and whose ashes are in a can inside their meager cave-like dwelling – is buried under a giant camphor tree” (Wegner, 2010).

The film, directed by Takahata, is based off Nosaka Akiyuki’s short story of the same name. Nosaka is one of Japan’s great postwar novelists, and depicts the scene shown in the opening minutes of the film. Nosaka wrote Grave of the Fireflies in 1967, a month after his short story American Hijiki (a bitingly satirical post-war comedy), and Takahata’s 1988 film was its first cinema adaptation. In a 1994 interview (Animerica, p. 8) with Animerica magazine, Nosaka said:

“There were many offers to make that novel into a movie, but they never materialised. It was impossible to recreate the barren, scorched earth that’s to be the backdrop of the story […] what if a kid with a fat belly showed up to play him [Seita]?”

Takahata further explained the rationale behind the animation war story in the same interview (p.7):

“It’s natural that many that many animated stories are adventure stories, and that’s not a bad thing in itself. But at the same time, I’ve felt a contradiction in that… Whether it’s animated or not, a wartime story tends to be moving and tear-jerking, but the young people reading or watching such a story have a certain inferiority complex in relationship to it. They think that people back then were much more noble and they wouldn’t be able to do such things themselves. But I think that’s not right. We make such stories to give people courage, but then the audience feels that the story has nothing to do with them. So I wanted a common ground for the audience to relate to. If felt that way before I encountered the [Nosaka’s] book.”

The director confirms that, even in 1980s Japan, animation was associated mostly with adventure stories and children’s cartoons, making Grave a significant departure from the approach of prior formats (Animerica, 1994, pp.7-8). Yet its double-feature release alongside My Neighbour Totoro shows that Ghibli intended the film to be seen by children — an unusual approach, to say the least. So what is found in Takahata’s sobering war story?

Grave of the Fireflies opens in the Japanese city of Kobe in the aftermath of the Second World War. The opening scene depicts the starvation death of Seita, a teenage boy, in a train station where he joins his sister as a spirit. The film then cuts to the waning days of the war, as Seita’s mother and five-year-old sister, Setsuko, prepare to evacuate their home in anticipation of an air raid. Moments later, the bombs arrive but not in the expected form — long, thin incendiary tubes land and set fire to their home and neighbourhood. As a firestorm grows and consumes the city, Seita and Setsuko seek shelter, having been separated from their mother. By the time the fire is extinguished, Kobe is scorched and barren — little remains but Meiji stone department stores and concrete schools. Seeking shelter at a local elementary school, Seita is informed that his mother was badly burnt in the raids. Within days, she dies.

With their mother’s passing and their father overseas in the war, the children are taken in by distant family and relocate to the countryside. Seita sells his mother’s remaining possessions and retrieves their buried supplies, giving it all to his aunt, who uses the proceeds to purchase rations. As the supplies begin to stretch thin, and the number of mouths to feed in the home increases, his aunt becomes increasingly resentful towards their presence, since Seita has no job or income. This culminates in an argument that results in Seita and Setsuko setting out on their own, establishing themselves nearby in an empty bomb shelter that sits on the edge of a small lake.

At first, Seita and his sister are triumphant at their independence and freedom by the lake. A scene sees them capturing and releasing fireflies in their small, cave-like shelter, only for Setsuko to find them dead the next morning. She asks, “why do fireflies have to die so soon?” As food becomes scarce, Seita provides for them by stealing from the fields of local farmers, who eventually catch him and assault him. Setsuko grows increasingly ill, and when Seita takes her to a doctor he confirms she is dangerously malnourished. Seita goes to withdraw the last of his mother’s money from her bank account, but on his way back to the shelter Japan has surrendered and, since her navy was sunk, his father is almost certainly dead.

Satsuko is delirious by the time he returns, and although he attempts to feed her she passes soon after. A scene shows a wealthy family returning home from the country after evacuation, indulging in music and small-talk, as glimpses of Setsuko’s life in the shelter are shown. Seita cremates her body at the top of the hill, and retains only a few small personal items in her memory. He starves to death in the weeks following surrender, joining Setsuko’s spirit. In a haunting image, they settle beneath a view of modern-day Kobe, aglow in the prosperity of the postwar world.

It is unflinchingly tragic, but also in some ways more sentimental than Nosaka’s own experience, who survived his sister and died in 2015. As Takahata explained, Seita reflects a postwar generation, as “he withdraws to go away and do other things. He doesn’t endure it” (Animerica, 1991, p. 7). Takahata positions Grave not as a traditional anti-war film in its tragedy, despite his well-documented antiwar advocacy, in favour of an intimate story of the consanguineous bond of brother and sister, and their death in isolation. We recall here the “New Japan/Old Japan” anxiety of the previous chapter on Only Yesterday, but its dimensions are replaced. ‘New’ and ‘Old’ are not broad notions of old agrarian Japan and new consumer society, but of old childhood in the Second World War and new childhood raised after it. So there like a lot of Takahata’s films, Grave invokes a dialogue between the time of a film’s release and the time of a film’s setting.

This is why Goldberg (2009, p. 41) suggests the use of luminous fireflies as an image of “[remembering] this wartime history paradoxically through the act of viewing the natural,” bridging the irreconcilable suffering of the war and consumer society shown at the end of the film through a natural paradigm. This is helped by the illustrative nature of animation — the fireflies mirror closely the burning spot-fires of Tokyo, in the same way that our protagonists depict the idea of a brother and sister transcendentally, rather than literally as in live-action cinema. This produces an effect that paradoxically distills the brutality and tragedy of the film, immersing the audience in their feelings without distracting them with the detail of a living human actor. This better orients characters spatially, since they are depicted in the same transcendental approach given to background watercolour and lighting cels.

To close the argument portion of this thesis, it seems appropriate to draw parallels between Grave and its sister film Totoro through Karatani’s initial observation on the upheaval of the old, transcendental understanding of landscape. It is easy enough to draw parallels between Grave’s retreat from society and Only Yesterday’s similar modern phobias. More critically, considering their cinema pairing, consider how aspects of Grave’s landscape mirrors Totoro’s own pleasure amidst the trees; particularly the scenes in which Satsuko plays and acts out adult chores around their abandoned shelter. Wegner (2010) also draws parallels between the shelter the natural world provides in Totoro, nurturing the girls, and Grave’s “fully objectified mute landscape, [which] appears glacially indifferent to their suffering.” Their shelter sits on a lake, across from where large country houses look over the surrounding countryside. There is some fantasy at play here, between the misery and rationing of the Japanese society and the freedom and peacefulness of the shelter. Of course, the children never really escape from the war-world — they become increasingly dependent on it, as Setsuko’s health deteriorates. These desperate scenes starkly contrast the peaceful and intuitive relationship between person, agriculture and wilderness depicted in Totoro, and constitutes a dystopia that inverts several the picturesque, utopian deconstructions of modernity argued for in this paper’s first chapter. This is a good way of demonstrating the complementary, rather than antagonistic nature of the utopia/dystopia paradigm: we can trace the ‘social dream’ in both, precisely because of their opposing thematic constructions — dystopia is most commonly an inversion, rather than a subversion, of the utopian social dream (Wegner 2002). The dream may be different — Takahata clearly outlines a dialogue between the youth of consumer society and the abstract suffering of the war years at the beginning of this chapter — but as a double-feature, and as a text preceding Totoro’s ‘50s pacifism, Grave’s haunting echoes of the past reflect a radically different visions of Japan’s 20th-century landscape.

Conclusion #

Although the five films pulled from Studio Ghibli’s thirty-year “golden age” might seem to constitute a varied selection of cinema, reflection on the arguments made across the five texts suggest their appropriateness for use here as elements of a single argument — what components of Ghibli’s spatiality contribute to its importance in ongoing analysis into animation? Each film offers a unique dimension of spatial thinking, and helps build a portfolio of texts that testify Ghibli’s strength in depicting and moving around landscapes.

Hence the title of this paper: A Universal Nostalgia — “universal” by way of the mechanics of Ghibli spatiality. Throughout this broad filmography there are recurring political themes (in perhaps the most obvious framing of utopian thinking), but we can also see utopian effort arising from the mechanics of the studio too. This is how hyperlocal texts like Only Yesterday, in its midcentury parade of Japanese memory, and Whisper of the Heart, in its championing of urban Tokyo spaces, can become universalised to audiences foreign to both Japanese urbanism and the Shōwa/lost decade periods. The arguments of this thesis are less concerned with the spatial characteristics of any single film than it is with how different strengths of different films across Ghibli’s catalogue can make a convincing argument for the studio’s relevance and usefulness in both the structural and textual dialogue around animation. This made a good excuse to revisit and assess some of the studio’s most memorable, and often less-discussed, works across the last forty years and map them against their spatial strengths to produce a convincing portfolio of utopian spatiality.

The first section of this thesis, titled Spatiality and Abstraction, looked at two of Ghibli’s ‘lost histories,’ or films that depict alternative pasts in the real world. These films constitute the most fantastical among the texts analysed in this thesis. Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro, represents the heart and initial inspiration of this thesis, because of its obvious agrarian whimsy and Wegner’s (2010) powerful argument for its understanding as alt-history. It introduced a conversation about modernity we saw recurring throughout the subsequent chapters, but positions itself more generally, depicting an ‘alternate Shōwa’ that could very well be an ‘alternate agrarian Britain’ or ‘alternate postwar Europe;’ highlighting the some of the similarities and many of the vast differences between Japan’s war period and that of the pre-war West. This is Ghibli at its most subversive, due to its restrained depiction of utopian agrarian life and the small-worldness of childhood. It presents utopia as a conceptual dream, rather than as dry political fiction, which is made powerful by its gentle abstraction and pastoral universality. Although other Ghibli films indict and critique real places and times in history, none do it as quietly and convincingly as Totoro.

My Neighbour Totoro’s ‘abstract Japan’ is followed by an ‘abstract Europe’ in Kiki’s Delivery Service, the subject of the second chapter. As siblings of the Spatiality and Abstraction section, Kiki’s urban European port town is closer to Totoro’s agrarian Japan than it first appears, largely bound by their mutual fascination with and deliberate recreation of the midcentury period in their respective landscapes. Where Wegner saw a 20th-century vision of Japan that had never gone to war in Totoro (2010), A.J. Rocca saw a “ghost of modernity” in Kiki’s Delivery Service (2017), that, similarly, had survived into the postwar period only through the abolition of the Second World War itself. This leaves the section with two key arguments, drawn from analysis of each chapter. First, that Ghibli films (as directed by Miyazaki) show a fascination with the rebuilding of history, reinventing and immersing old spaces and building out of them ‘ghost pasts’ that never occurred in our own world. Looking backwards from the 21st century, these ‘ghost pasts’ are depicted in the abstract, told only through local stories of local significance, lending them a vague universality that traditional science fiction often dismantles. It is precisely this abstraction, and the deeply human and empathetic depiction of our girl protagonists, that allows these places to live on as believable worlds in our minds.