NEW Story: Sunday Morning

The Atlantic Bulletin

From the Editor #

Welcome to the fourth issue of The Atlantic. Good posts this month. Bit of a smorgasbord, with stories covering all sorts of things. Most importantly, as was mentioned last month: I want to start a comic.

How do you go about starting a comic? I don’t think there’s much of a trick to it, as a first-timer — you just have to ’start’. It’s difficult for me, not just because I’m still learning to draw, but also because a comic in the Vekllei format should help the utopian ’social dream’ of the project — that’s what the “author” category of posts means. So a comic would not just have to tell an exciting story with a linear plot and action — it would have to be immersive; a guide to the world; something you could revisit time and time again without needing to follow a linear story. Figuring out how to do that is complicated. I’ll set aside some time in September to start exploring this concept seriously.

I’d also like to do a short animation/music video for a bit of fun. 80s technopunk vapourwave irony aesthetics are last year — what about a bit of postwar austerity to anticipate the coming global recession? Forget bright-coloured sneakers and Windows 98 interfaces — how about some council housing and cardigans?

I guess we’ll have to wait and see.

Thanks for reading, and I’d also like to thank the contributor to this edition, Bike (Milky), for their wonderful essay on Vekllei ecofeminism. It’s an excellent read — check it out below. If you would like to contribute to The Atlantic with writing, art or reviews relevant to the spirit of petticoat ideology, please contact Hobart at [email protected] before the 30th of September.

Thank you for supporting Vekllei, and best wishes.

Hobart Phillips Enjoy — 楽しんで

I. News & Announcements #

- I’ve gone back to work at the news organ I used to work at — I might have a little less time, but I’ll have a little more money, and that’s nice. Hoping to draw more in September, riding off the fun I had in August.

- The wiki (called Zelda Wiki — good luck buying any domain with the word “Zelda” in it) is coming along well. Rather than writing every article in advance — a leviathan task — I’m preparing a few intro covering the country of Vekllei and the characters of my story. It’s live now — but good luck finding the URL for it. It’ll be done before the end of the year, but it’s not nearly finished yet.

- The post “Absolute Quiet” really took off on reddit and netted me nearly another 1,000 subscribers on r/vekllei. Awesome! It’s not hard to cross-post work and it pays off, especially as I get better. This piece worked out really well — if only I could paint cities as nicely. That’s a long-term ambition, unfortunately.

- The website is “functional” in big scare-quotes. It’s just a blog replicating reddit posts for now — that’ll change once the wiki is complete and accessible. The parallax isn’t cropped properly on mobile and there’s a few errors with icons loading in, but it’s better than the broken hub with no content that was there before.

- As a reminder, www.millmint.net and www.vekllei.com now redirect to www.millmint.studio!

II. Tzipora-watch #

In August of 2067, Tzipora wrote to the office of the Sun-Cola Beverage Company professing a love of their soda. The letter was so heartfelt and congratulatory that the chief operations officer invited her to tour their bottling plant in Demon, during which she met several of the staff responsible for her favourite flavours. They sent her home with a basketful of Sun-Cola merchandise and a wristwatch shaped like a bottle cap that still works to this day. Tzipora made a habit of writing to her favourite companies, and as a result has visited a lot of places of industry the ordinary person might never think to go.

III. Vekllei Fact of the Month #

Despite the prevalence of nuclear power in Vekllei, over 60 per cent of the country’s civil power is produced by geothermal and hydroelectric power stations. This is in part a result of Upen’s intuitive emphasis on renewable local resources (not just for sustainability, but for deep integration and dependence with the physical landscape), but also because much of Vekllei’s nuclear power is sold abroad via undersea powerlines in Europe and the United States, to supplement ageing fission plants.

IV. WordBook #

Endoanotetmouisa — translates literally as “Princess belonging to the Earth,” often mistranslated as “Princess of the Earth”. A highly uncomfortable nickname given to Tzipora in a news article written about her, shortly after her first mainstream appearance — a student documentary about building her house in Montre-Lola. Her interviews in the film sparked widespread interest in the girl, both for her medical condition and her extraordinary childhood, and so she spent much of the summer of 2083 in the Azores trying avoid this nickname.

V. The Bulletin #

Absolute Grotesque #

📖 Published 31st August 2020 | Read here.

On the morning of the second day, I watched a fly crawl across the cheek of the middle-aged woman, probably an office worker, lying next to me. It moved up her cheekbone to her temple, stopping now and then to rub its front legs as though performing a ritual. A jagged tear ran down the leg of her dark blue work trousers, but the white calf it revealed was miraculously unscathed. The woman lay still. Probably dead, I assumed. After a while, the fly got on to her eyelid. Suddenly, she reached up and brushed it away, opening the eye. There was still a moist light inside.

From Insects, by Seirai Yūichi

By chance, the glass paperweight had survived. When her in-laws’ house had burnt down in Yokohama, the paperweight was among those things that she’d frantically stuffed into an emergency bag, and now it was her only souvenir of life in her girlhood home.

From evening on, in the alley, she could hear the strange cries of the neighbourhood girls. Rumour had it that they could make a thousand yen in a single night. Now and then she would find herself holding the forty-sen paperweight she had bought after ten days of indecision when she was these girls’ age, and as she studied the sweet little dog in relief, she would realise with a shock that there was not a single dog left in the whole burnt-out neighbourhood.

From The Silver Fifty-Sen Pieces, by Kawabata Yasunari

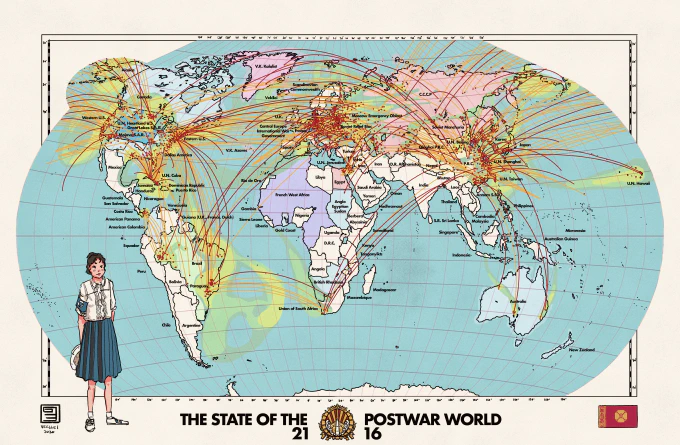

On the 14th of August 2111, the Atomic War began in a Chinese submarine in the South Pacific, and ended six hours later. The war marks the single greatest loss of life in human history and would disrupt human life on Earth in previously unimaginable ways — consumer society bottomed out, the world became small, the Earth grew cold, and a new chapter in human history was opened.

This political map marks the territories of Earth as they stand five years on, in 2116. There are fewer countries in the world today than in any other point in human history, in part because the catastrophic reduction in human population — some 520-600 millions in the first year — has emptied out countries and rendered others uninhabitable. Many of these territories here are disputed and, in some cases, autonomous — for simplicity, they are presented as they are recognised by the U.N. The map also presents a long-exposure view of the war as it happened, and its remaining fallout currents today. Red dots mark significant nuclear detonations on August 14th. Yellow dots mark surface warfare in some capacity. Red trails mark missile flight, reduced in number here by strict denuclearisation treaties of the decades previous. Yellow trails mark the flight paths of atomic bombers, both supersonic and subsonic. This map does not record failed launches, intercepted missiles or downed aircraft.

Fighting was arranged along political axes — namely Western (U.S., U.K., West Germany & N.A.T.O. members), Warsaw Pact (U.S.S.R., Cuba, Egypt), East Asian (China & Korea), and non-aligned (Vekllei, France, Brazil). The war experience was unique to each country — Vekllei exchanged warheads and bombs with China but not Warsaw countries, the U.S.S.R. exchanged with both Western and East Asian members, and Brazil fought a catastrophic war against both Soviet and American territories. The immediate aftermath saw a quiet Earth, much of it scorched. Temperatures dropped by 10 degrees centigrade for the first six months, and slowly warmed as debris cleared in the following years. Wide-scale firestorms were tempered by rains that followed the war shortly.

Some 274 millions of the dead are accounted for in China, where in 2116 the cities still lie in rot, swollen with corpses; heavy with miasma; concrete dams bleached and cracked; the wood all burned up; the rivers warped and quiet; dead fish along them; a surfaced water main weeping blood; harsh asbestine whistling; railcars in a ditch; sloughing skin; tremors; smoke with no fires; confused wandering; bleeding from the inside; families-as-sand; sand-as-trinitite.

Exchanges were confused, helter-skelter, and the combatants rattle off like a death snare. The U.S.S.R., the U.S., France, and Vekllei all exchanged death with China.

It would take more than mere annihilation to extinguish the P.R.C., but the toll was nauseating. Beijing and Shanghai were simply disappeared; there was nothing where there once was. The fistfuls of rebar and concrete amidst glassy, ossified landscape were heaped into direct administration of the U.N. The following year, 40-120 million more Chinese would succumb to the greatest famine in the history of the world. Of course, in the U.N., there was good argument for the nuclear retaliation — China launched first; why should money and food go to the perpetrator of the vastest disaster in human history? One can’t help but wonder if the life of an Oriental coolie wells fewer tears than his equivalent in Paris. There are not enough flowers in the world to pay tribute to the dead of China, who were simply dispensed with in European memory and subsumed in part by the United Nations. The communist party would continue to control the vast interior, divided into two states by ethnography, where 1949 seemed closer than ever. Necrotic politics are legitimised in the land of the dead. Soon, we saw the consolidation of nation-states into geographic regions with a disregard for ethnography not seen since the colonial years. This was met with violent resistance in some places — in others, locals capitulated to the extraordinary hyperreality of the postwar world.

The United Nations was quickly catapulted into the status of a de facto administrative world government in a last-ditch attempt to ‘freeze time’ as it were, in order to provide the superpowers time to recover from the scope of immediate devastation and prevent humanity from entering a long period of decline. This involved the moving of soldiers on a scale unseen since the World Wars, as U.N. international brigades propped up vulnerable, scorched territories in Central/Western Europe and Asia. The immediate peace of the first days after the war was ruthlessly enforced — and strategic opportunism was threatened to meet indiscriminate violence and U.N.-sanctioned nuclear retaliation. There was some belief that the status quo could carry on. So troops of non-combatant countries were supplied, and in some cases press-ganged, into this global mission.

The battered United States, acknowledging its ‘century of decline’, found itself consolidating control over its urban, though devastated, coasts. The awkward appellation “Dallas America” was used as a colloquial shorthand for a disputed territory that insisted on referring to itself as the legitimate United States. The name was only superseded by the ridiculous “United Nations Heartlands of the United States,” the Aid Region of the U.S. interior that had collapsed in the days after the war. This was buffered by the Mojave and Great Lakes Special Administrative Regions, federal territories that contained war industry and nuclear infrastructure that propped up the precarious coasts. Despite efforts to revive agriculture in the scorched U.N. Heartlands U.S., starvation was met with martial law along the coasts the following year.

The U.N. was granted temporary, direct control over several collapsed territories that had either succumbed to nuclear fire or had caved to anarchy in the weeks and months after. In some cases, like the U.N. regions in Hawaii, Jerusalem and the Central Europe International War Government, these behaved as states in themselves, administrated directly by the United Nations Mission for War Recovery. In others, they were merely named as such with the vague promise of future aid. U.N. Cuba and U.N. Taiwan were such examples, in which devastation had been so catastrophic that little remained to govern, and the local population was mostly left to anarchy. In general, there were great inequalities in how the U.N. chose to dedicate resources, largely informed by its largest nation-states and political interests.

There are thousands of stories from communities and territories across the world directly impacted by the war — from the atomic bombing of Sydney to the catastrophic reactor meltdowns of Brazil’s south. The war was unprecedented in scale and devastation. This map reveals little of the profoundly human tragedy that was brought about, nor does it invoke the difficult existential artefacts that are still being reckoned with. Perhaps humans are just animals after all — destined to die out the way so many have in this age. Most tragic was not the colossal scale of death, or the collapse and pain that followed, but the upending of domestic society into violence, in which people of consumer society — the middle class — found themselves with not much at all, thrust into a world of chaos and suffering in which all prior epistemologies evaporated. Like the flash of blue light that preceded the roar, it was the stuff in supermarkets and department stores that marked the absolute grotesqueing of life in the new age.

2,000 members! WOW! #

📖 Published 27th August 2020 | Read here.

Hello,

I’m Hobart. I’ve been working on this project for a while now. It doesn’t really have a purpose or an end goal — I just want to draw and write about nice things, and I’m learning a lot on the way. Welcome to everyone new here. I don’t really have anything to sell, I’d just like to thank you for tuning in and checking Vekllei out.

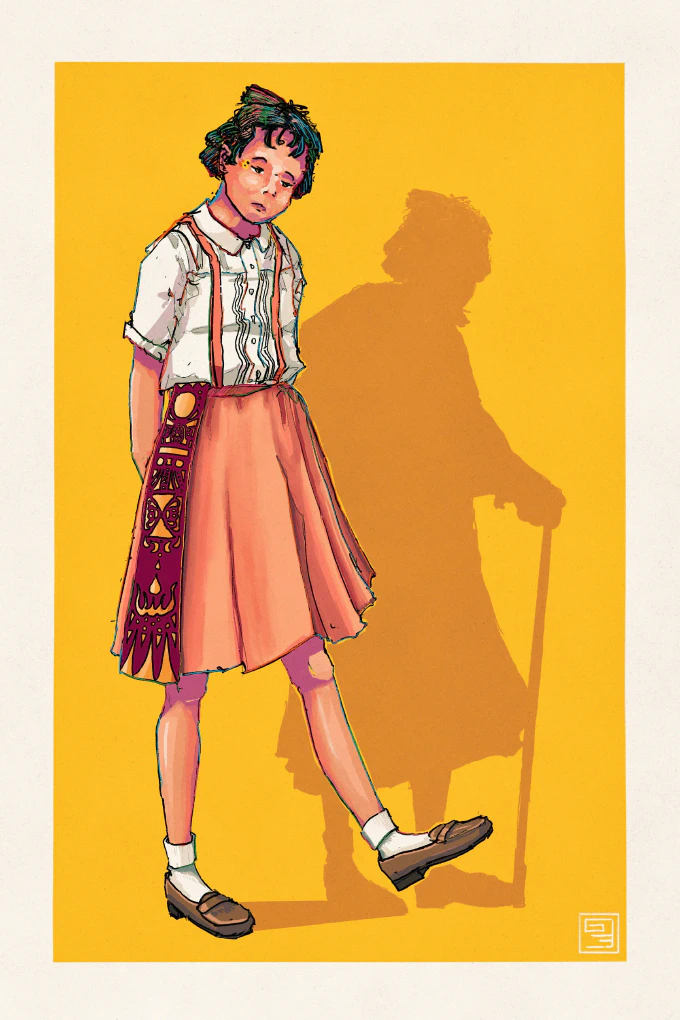

I’ve drawn Tzipora here as a sort of Sailor Moon knock-off. Good show that. The Japanese intro is very nostalgic, I’d love to do a little animated short in that style.

I post about twice a week. I do a bit of everything — machines, maps, characters, landscapes, architecture, etc. I’m truly a master of none.

You can come join the Discord if you’d like — it’s just a quiet community to share interests and talk: discord.gg/dCE6vSU

Otherwise, I’ll keep doing what I’m doing and you can keep liking my stuff (please). If you have any questions about the project, or just want to introduce yourselves, here’s a good place to do it! Thank you kindly to all commenters, readers and friends of the project, whether you’ve been here for years or for six hours — it’s very special to have so many people interested in work that’s so close to my heart.

Keep on keeping on,

Hobart

Absolute Quiet #

📖 Published 24th August 2020 | Read here.

There were plumes in the sky, sent from bunkers buried deep in the well of the Earth, killing with switches. Vekllei went to war, and so Tzipora went to war with it.

The throbbing machinery of another world began turning, and anyone who saw the bomb would hear it. Passing seconds dislocated and caught heartbeats. The plumes were pretty. It was such a shame, those plumes. It was a quiet afternoon in the flower-tundras.

There was an absolute quiet among the grasses, and peace in her heart. She had work to do. She was a warden, after all — and she’d done a good job spotting the missile before the sirens caught up. In truth, any devastation seemed incomprehensible. The flower-tundra would last forever. But that was her job, and she had to do it.

She left her bucket by the freshwater creek, intending to retrieve it a while later. The drinking water tasted better up here. She turned from the plume and followed the moss path out of the flower-tundra. Her village was before her.

So ended the old ways and so started the new.

Rural Newda in Rural Vekllei #

📖 Published 17th August 2020 | Read here.

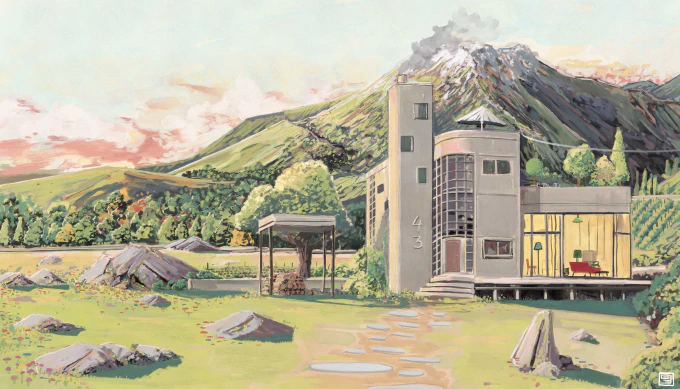

New gouache brushes, this painting was done on a single layer. turned out pretty good. more paintings to come.

Newda is Vekllei’s national architectural ideology, applied flexibly in a range of modernist styles developed domestically in her architecture schools. Broadly, Newda buildings emphasise distinction from the surrounding landscape (called Dumousiantopet, or ‘beautiful and seperate’), natural decay, and honesty in material and construction. Vekllei’s great Parliament House is Newda; as are the little rural homes found in the mountains inland in Vekllei.

Tzipora’s house in the village of Montre-Lola (as depicted on the map here) is built in what Vekllei calls “Azores revivalism”, a Newda style heavily influenced by the stripped deco and streamline moderne buildings of a century prior. It is part of a constant conversation Newda holds with its past, as both a deeply modernist, progressive school and one bound up in the wider aesthetic and cultural traditions of Upen, the spiritualism of Vekllei.

Her house is small, but appears larger due to the layout of the structure. A small sleeping loft sits atop the living, bathing and cooking areas of the home, and opens out into a private rooftop garden. The utilities tower also hides a small staircase leading to the roof, which is also accessible for outdoor recreation. Her home stands amidst the farmland of Montre-Lola, and very near the library and primary school where she works. Her property is marked at its end by a creek that runs into the Dentre River. She has a vegetable garden in her backyard, and shares her paddocks with her neighbours for grazing periodically throughout the year.

Her house was erected in gratitude by her neighbours out of prefab components, and assisted by a “construction line,” — a temporary rail line in which goods are delivered and cranes are supported, minimising the need for lorries. Houses of this type and period are rarely seen in agricultural settings in other countries, but in Vekllei, where Landscape has been abolished, there might as well be no difference between a building suitable for the cosmopolitan, coastal cities and a dwelling for a farmer-girl.

The Thousand-Year-Old Girl #

📖 Published 12th August 2020 | Read here.

The concept of living forever jumps out at people uncomfortable with their own existence. There is a contemplative instinct among educated people that — if they could simply will themselves into a state of self-actualisation — death would only be an obstacle to greatness.

As Tzipora found out quickly, the opposite was true — death and temporality were wells of meaning against which all great people, beauty, and human constructions were cast.

Tzipora Desmoisnes is what is known as a Gregori Baby, a catch-all term for a unique genetic condition that has seemingly produced a variety of miracle children appropriate for the frothing futurism of the atomic age — boys and girls who, suspended in the purity and good-naturedness of childhood — live forever.

There is no single “Gregori Baby” — each is unique, and Tzipora is the 13th to have been recognised overall. The phrase is a shortening of Gregori-Heitzfeld syndrome, a stand-in for medical information that isn’t there. The first, Gregori Hordiyenko, was born in 2024. He was healthy, and died of unrelated causes in his 20s. Tzipora, at 13th, continues to live to this day and is the oldest person on Earth.

There is a disturbing trend among the Gregori children, first heralded as miracles and symptoms of the space age, to deteriorate medically as more are born. The culprit is the malfunctioning of telomeres in their DNA — the source of their longevity — which regularly produce devastating chromosomal disorders, including Trisomy 13 & 18, killing most “ageless children” before their third birthday. Those that survive are often victims of a severe anaphylaxis caused by a hyperactive immune system — rendering many of them permanently sickly. Others find themselves unageing, but continue to grow — reaching as tall as 2.5m before their bodies give out from exhaustion and osteoporosis.

So what is Gregori syndrome? What does your average (healthy) Gregori baby look like? Their genetic miracle is linked to the structures of the body that activate at puberty, and so girls vary between 11-16 years of age at onset depending on many factors that affect their development. Boys tend to be a little younger, from 8-14. Between the two, girls tend to be more stable, and all but two of the supercentenarian Gregori children are female.

Among girls, they are prepubescent and generally stop ageing on the eve of menarche, or their first period. In Tzipora’s case, her body is estimated to be 13 years and 11 months old. Unlike many Gregori children, Tzipora lives in a wealthy country and has volunteered for extensive research into her genetic makeup, meaning that much of early medical documentation around Gregori-Heitzfeld syndrome was received directly from her case.

Most obvious is that, at a foundational level, her cells are similar in function to unipotent stem cells, and have been since hormones at the end of thelarche suspended her ageing. This change has occurred somewhere in her DNA — exactly where is unknown — but the end result is that, unlike regular progenitor cells that make up most adult bodies, the building blocks of her body are capable of cell-renewal. Her telomeres, the endcaps of chromosomal DNA in mammals, are undamaged. And so there is an amazing shift in her basic human structure — in which human cell lineage, which usually ends in a mature cell incapable of division, is caught and rearranged. With this considered, it is no wonder that Gregori children suffer from such catastrophic chromosomal instability, and why healthy ageless babies are a rarity. Her body is not exactly a “body of stem cells,” but for their function in a healthy Gregori child, they might as well be.

So it is that nothing about Tzipora is changing. She suffers from pains in her legs often — called growing pains, although they are not from growing — and her cells continue to replenish, albeit at a rate 1.25 times that of normal people. She is, in essence, “growing” as any other premenarchal girl would, but she is not getting bigger or becoming older.

Tzipora is blessed with an adult life in Vekllei, where the “Child” does not exist as it does in the West, and her individual freedoms are far-ranging. She may smoke, and drink, and has held many different jobs in her life. She holds two doctorates in English and Vekllei Literature. She is obviously sterile — even if she were to somehow “age out” of prepubescence into pubescence and receive the required hormones, she simply lacks the genetic code to reproduce — but raises many children through her active participation in village life and her roles as Montre-Lola’s municipal and school librarian.

In other countries, with coded roles for children, their problems are much greater. Unable to form adult relationships and often incapable of finding work, many work in entertainment or fall into poverty as they outlive their friends and parents. Socially ostracised and forever young, many are victims of superstition and fear. As the pattern of Gregori children indicates an increase in mortality, even as more are born, their appearance is both a miracle and a tragedy — ageing not through mitosis but through weathering the societies in which they live.

The 31st Century — Vekllei throughout our Solar System #

📖 Published 9th August 2020 | Read here.

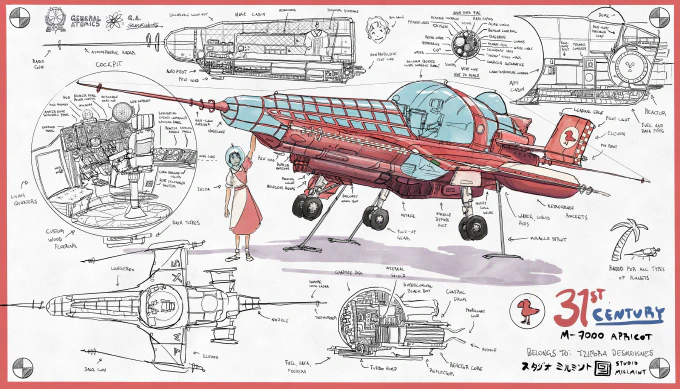

We’ve spent a lot of time in the 21st century — but Tzipora is biologically immortal. Where does she go from here? Well, let’s enjoy a small glimpse at that future together, by winding the clock forward one thousand years.

By 3076, our Solar System is a pleasant place to be. Most of the planets we once gazed at from afar are now habitable and lived on. The Great Epoch of Rest has begun.

There is no great interstellar empire, no rise and fall of spacefaring supernations — a Vekllei way of life is now lived out in multicultural, prosperous clusters of people across our Solar System. The ordinary person is afforded incredible freedoms previously reserved for science fiction through the accessibility of personal light spacecraft, translated literally as “boats”.

This here is the M-7000 APRICOT, manufactured by the Government Aerospace Factories (GAF) of Vekllei. Many companies are contracted by the GAF, including General Reactor, to whom this boat lends most of its flight control systems and all of its power plant. It is a light, personal boat for women built in 2807, making it relatively unique in both its 28th century design language and its gendered marketing. While the personal boat market was growing rapidly by this time, the vast majority of owners and pilots were men. The APRICOT set out to change that, and Tzipora, the world’s oldest living person with a youthful face, was among the first to demonstrate the accessibility and freedoms of space travel for women and girls in the personal boat market. It was her first boat, and despite its orientation for women it was christened with a male name: BARON.

It is a comfortable and pleasant craft that can be lived in for extended periods of time. Tzipora has done just that, travelling to stars in search of water-planets with Micronesian archipelagos, where she likes to spend most of her time. Its glass roof across the entire accessible cabin, including bubbled cockpit, gives it breathtaking visibility in the depths of space and the most scenic of planets alike. Like almost all spacecraft, it is unarmed, save for the pacifying “jazz” electric canon, named for its firing sound reminiscent of a double bass strum.

When she tires of being alone, she returns to her hometown of Montre-Lola in Vekllei frequently. Boats are usually parked at off-world stations, preserving the aerospace and quiet of the Solar System. Light speed is exceeded through superluminal travel. So-called black boxes require extraordinarily precise programming, since superluminal travel is in all ways but name time travel, and the universe does not tolerate time travel. Coordinates calculated in the universal pyramid system by a pyramid computer ensure that a vessel arrives when it arrives, so to speak. The alternative is going nowhere at all — there is no in-between.

Superluminal systems are affected by gravity, so any person looking to exceed the speed of light and subsequently visit other stars must take the highways beyond our home system’s planetary orbit and launch into so-called free-travel from there. There are only a handful of these highways — the solar system is very, very large, and human construction is very, very small.

There was an instinct among many people that human progress would naturally scale exponentially — these were extrapolated from the remarkable progress in the lifetime of Tzipora’s parents and grandparents, who saw canvas aircraft in their childhood advance to the landing of a man on the moon, and again in her own exaggerated lifetime, in which the provinciality of her youth has simultaneously seen an expansion and exploitation of the planets in our native solar system.

This curve of progress was not to be, however — and it also explains why we had such trouble meeting aliens in the first place. Part of it was simply that there are very few worlds with water that also formed earthlike landmasses nearby — there are many aliens, and Tzipora has seen many herself, but most of them are fish and fish-adjacent. The second is that, if there is civilised life out there, it has most probably encountered the same engineering truths that humanity did, in our great interstellar project of the last thousand years. Namely that, all accounted for, there is no use for wasteful megastructures when a small one will do. People are having less children — on Mars, Mercury and Neptune, the population is actually shrinking. What good is the so-called “ocean liner of the stars,” with a capacity of millions? There are around 12 billion people across the solar system today. Maybe another 8 billion in the Ala system. Maybe a few millions more who have simply given up society for scattered stars in our neighbourhood.

It is likely that if any other civilised races exist, they are simply of our scale, or have destroyed themselves completely in the reckless pursuit of expansion. Humanity is lucky not to count themselves among them.

The APRICOT is one of many models produced by Vekllei’s Government Aerospace Factories. It is now possible for the ordinary person to explore distant stars for themselves, granting freedoms unimaginable in a previous age. Such is life in the Great Epoch of Rest.

VI. The Post Office #

Not a Particularly Environmentalist Bunch: Vekllei’s Feminist Natureculture [NEW] #

BY MILKY#0144

All direct quotes are from Melon’s Reddit posts or saved from his previous website.

Think about nature. Picture it in your mind. What do you see? Are there any buildings? Do you see your friends, or any people at all? What adjectives might you use to describe it? How do you interact with nature in your mind?

There is a divide between human society and what is considered ‘nature’ – landscapes, national parks or forests, beaches, mountain trails, campgrounds… Nature is often seen as a place you visit and a place you come home from. A temporary escape from societal woes. A vacation spot; perhaps someplace nostalgic. A special area, with boundaries and signs and info centers, that should be protected. It has also been seen as something owed to humans – wilderness to be tamed and dominated, or land to be cleared, excavated, drilled, and paved for capitalist human use.

Traditional environmental ethics heavily involves romantic, heroic, and nurturing narratives in regard to the relationship among humans, nonhuman animals, and this ‘nature.’ Empathy, care, and connection have been key in ecofeminist discourse on environmentalism and nonhuman animal rights. These values are traditionally feminine, and environmentalism is often seen as feminine as a result. Terms like treehugger exemplify the feminine care given by environmentalists. Another term, ‘soy boy,’ does not necessarily point to environmentalists, but ‘soy’ being a feminine quality implies alternatives to animal products being something only for women.

Parallel to environmentalism being a feminine work, nature is often coded as female. Mother Nature nurtures living beings, feeding plants and animals alike. Western romantic authors wrote comparisons between women and nature and were inspired by both alike. They are something beautiful to look at and something to find inspiration in. They are pure and untouched until man/humans tame and mold them.

“Vekllei is a fundamentally female country. This is what petticoat society means.” This does not mean that the feminised, pure, idealised nature persists. Take our protagonist Tzipora for example. She is female, yet not an idealised maternal woman that could possibly be confused for a Mother Nature figure. She is an eternal child, neither pure or innocent, nor in need of care and protection. If we consider the following quote, however, we can see how Tzipora’s situation reflects or is reflected in Vekllei’s unique environmentalist situation: “Vekllei is not alienated from its landscape but exists very much within it. Vekllei people do not consider themselves different from nature – they exist alongside everything else in the landscape. Their environment is not exploited, and so its protection is not necessitated through its abstraction and alienation, of which environmentalism is a symptom (as a reaction to exploitation).” Though Tzipora is very different from the rest of her community, she is not alienated from those around her. She is enmeshed in Vekllei’s culture and society and dutifully participates in school and work. She is inseparable from her environment.

In fact, “Vekllei has abolished landscape, deconstructing its vicious abstractionism.” In Vekllei, nature is not seen as ‘other’ or as romantically female, and this binary of human/nature has been removed. Of course, it is impossible to abolish landscape and our artist would not paint and describe such rich landscapes if they no longer existed. Paintings of Vekllei often depict Zelda and co., concrete buildings, and railways contrasted with the country’s rolling hills, grassy plains, and volcanic rock. The combination of humans and both their built and ‘natural’ environs is what makes up the Vekllei landscape, as there is no separation in Vekllei between nature and society. Everything in each painting is the natural landscape of Vekllei.

So, what has been abolished is the idea that nature is another place, something separate than the culture of Vekllei. In the 2020 Vekllei Handbook, MelonKony writes: “We are not a particularly environmentalist bunch, since we’re not alienated from our land, and we’re certainly not sentimental, but we do understand the relationship our lives have with our surrounds, and the utility and protection of nature is important to us as a lifestyle and a spiritual tenant of Upen.”

If the respectful utility and protection of nature is important, wouldn’t such a way of living with nature, being human as part of the natural world, lead to environmentalism? Not necessarily. “Nature is a fellow social organ, like society or family, and so Vekllei is not ‘environmentalist’ in the Western idea of the word but instead makes use of and protects its natural environment for the benefit of both themselves and the land.”

Think now about what surrounds you. The air, your room, your home, your town, and beyond. When you think about what is important to you about the natural world, imagine what your Ghibli/Tintin landscape would look like. Don’t forget to include the buildings and people in your orbit. There is no real boundary between you and the community you live and work in and the larger “natural world.” It is all part of the natural world. No need to call yourself particularly environmentalist even if you care about the world around you. You are still just as enmeshed with nature as our Vekllei friends are.

VII. Gallery #

Warning: this gallery includes the postcards distributed to patrons. If you’re a patron and have not yet received your postcards, you might want to wait until they’ve arrived.

This month’s sketches, presented without context or or standards of quality. Contact Hobart at [email protected] for full-res versions of any images received in this bulletin.

Postcard 1 — Tzipora in Vekllei National Dress #

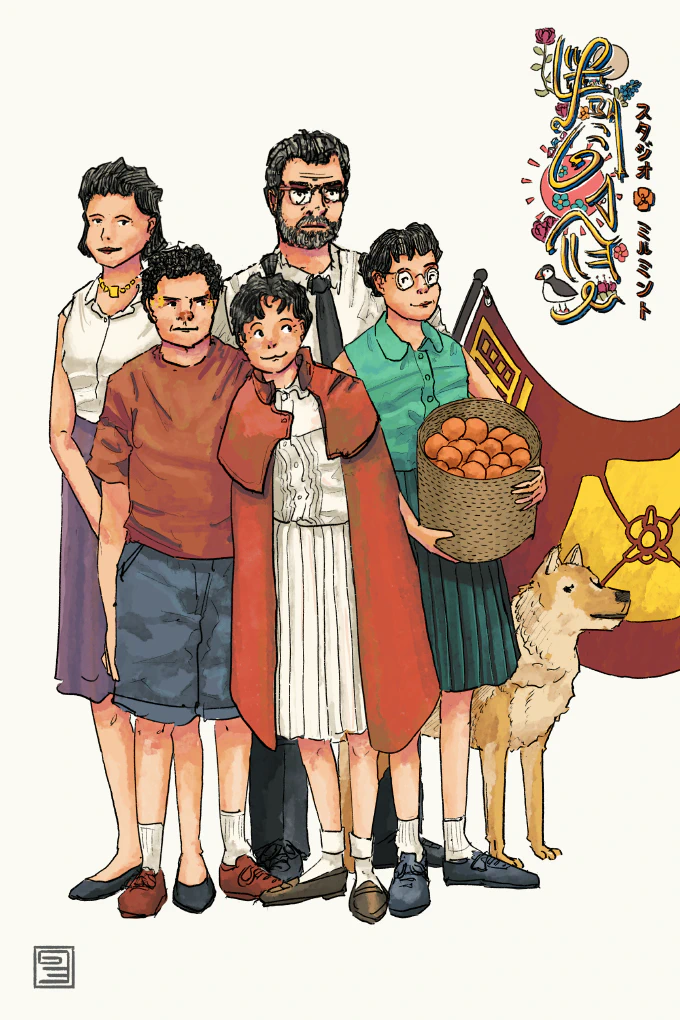

Postcard 2 — Baron, Ayn, Moise, Cobian and Tzipora #

Postcard 3 — Tzipora the School Librarian #

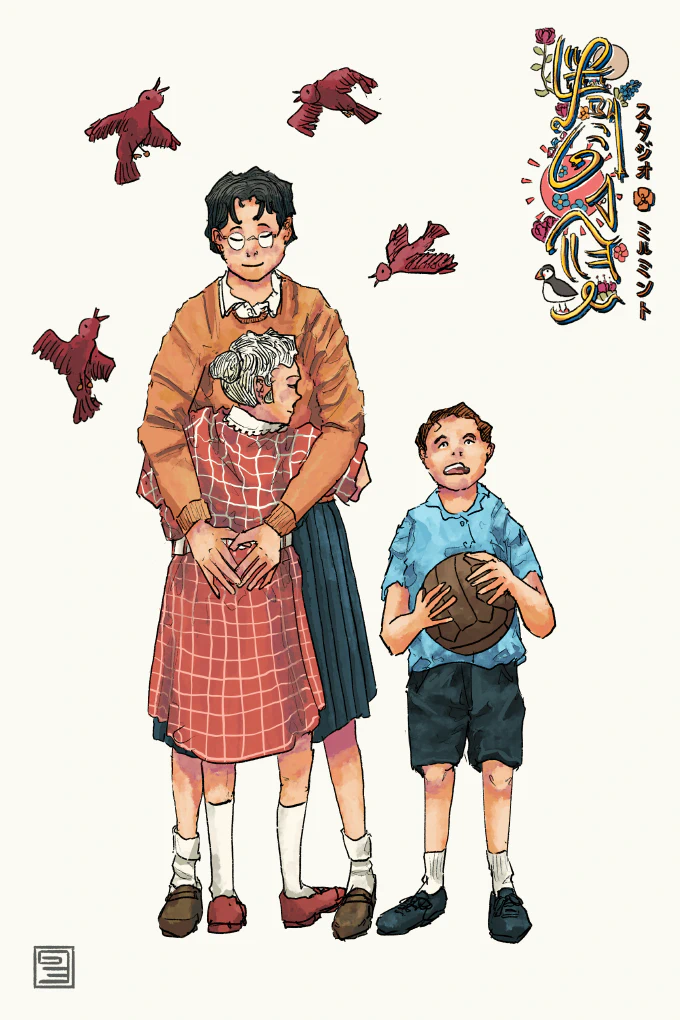

Postcard 4 — Cobian Sleeps Over #

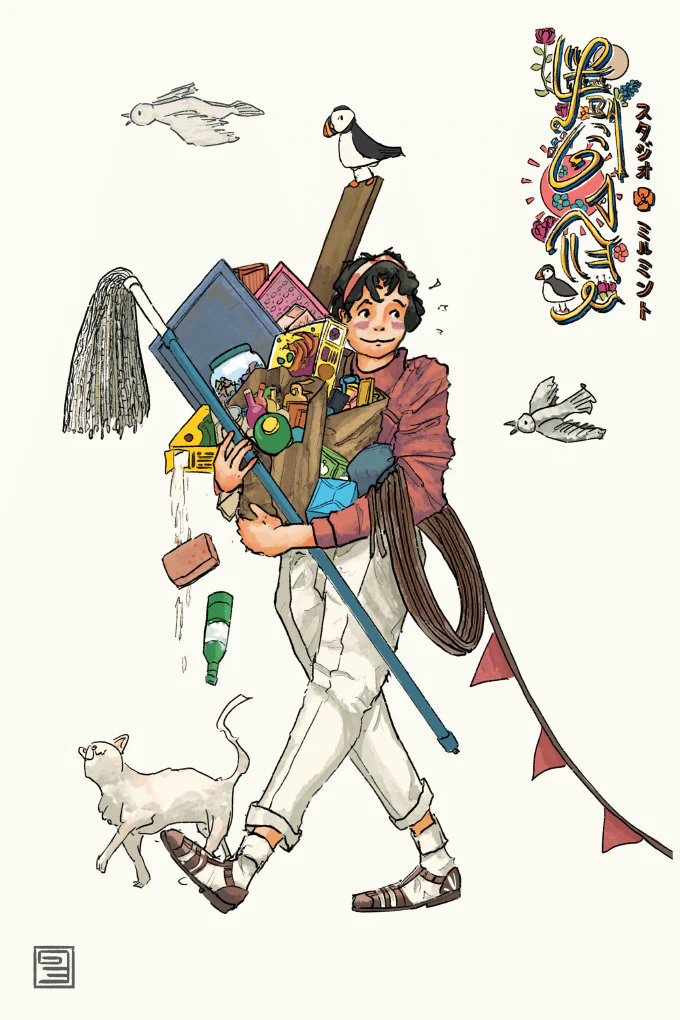

Postcard 5 — Cobian Catches a Ride Home #

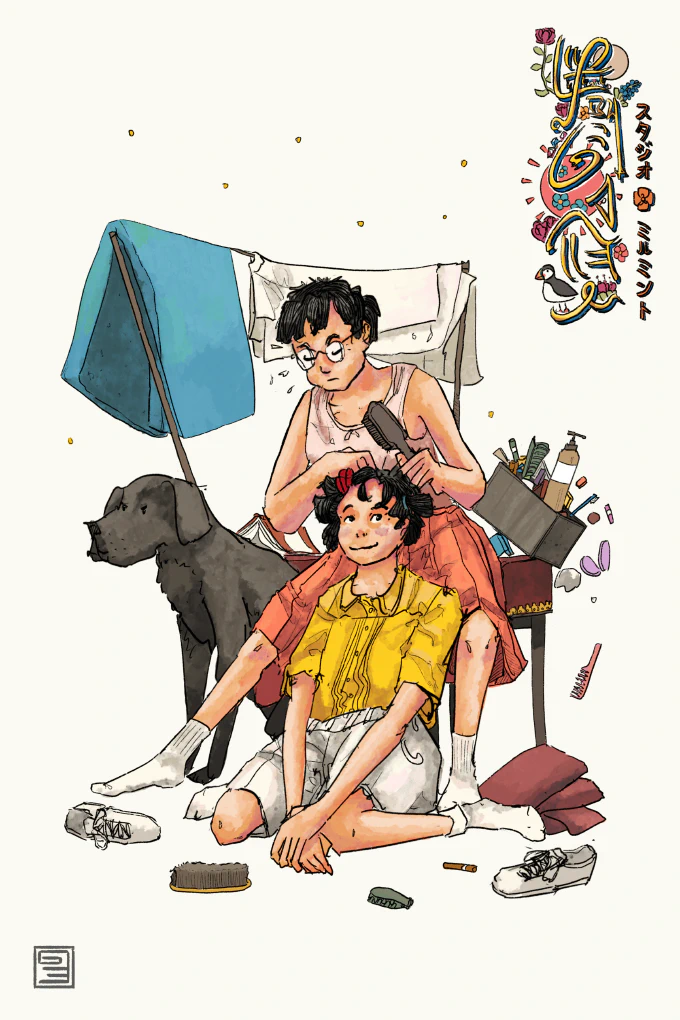

Postcard 6 — Spring Cleaning at the Desmoisnes Household #

POSTS THIS MONTH: 6 #

POSTS LAST MONTH: 6 #

Published by MillMint Press. Copyright 2020. To stop receiving these emails send UNSUBSCRIBE to [email protected].