NEW Story: Sunday Morning

The Atlantic Bulletin

From the Editor #

Welcome to the third issue of The Atlantic. This is the month of postcards, and feeling tired. There are fewer posts this month — and aside from Vekllei’s Race for Inefficiency, they’ve all been pretty tepid stuff. There’s good reason for that, and hopefully we’ll be back to regular production next month. And the postcards are currently making their way around the world — how exciting!

Where do we go from here? Am I just going to continue grinding out posts for the rest of this year? Well, possibly. But the theme of the last few editions, and of which July is no exception, is the “future” of this project — preparing to finally make Vekllei something “real". Worldbuilding is fine — but storytelling is a great human talent, and I would like to tell stories in Vekllei. I’m a bit boxed in, at times — distracted by nice things like postcards and university study, as well as regular posts and sketches — but I want to start something big. I want to start a comic.

Expect news next month.

In the meantime, the global pandemic has subsumed all of us into the surreal, and a lot of us lucky enough to be unaffected by Coronavirus are simply floating around, grasping for meaning and purpose in a world that seems as though a cosmic bit flipped somewhere after 2001. I’m sure I’m not the only one who, months into lockdown, is starting to find the abyss staring back at me. I think the way out of it is to draw more.

Thanks for reading, and I’d also like to thank the contributor to this edition, Mtirado, for their essay. If you would like to contribute to The Atlantic with writing, art or reviews relevant to the spirit of petticoat ideology, please contact Hobart at [email protected] before the 31st of August.

Thank you for supporting Vekllei, and best wishes.

Hobart Phillips Enjoy — 楽しんで

I. News & Announcements #

- Postcards have been sent! Finally — this was a mammoth task. Six illustrations back-to-back doesn’t sound like much, but I’m no good at doing the same thing over and over. Shipping may take up to four weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic, so hopefully everyone will have theirs by August. Let me know if you don’t.

- I have purchased some nice watercolour brushes for my digital workflow, and so you’ll see some rough edges in my work for a while as I learn how to use them.

- Absolutely no work has been done on the website. It’s a shame, but it’s a matter of time. It was always going to be a long-term, big-payoff project and when it’s done, it’ll be spectacular. Hopefully August treats it better.

- www.millmint.net and www.vekllei.com now redirect to www.millmint.studio! Makes it a bit easier to share.

II. Tzipora-watch #

It was in July that Tzipora first met Ayn’s parents, who would quickly assume a role in Tzipora’s life as her own grandparents. Ayn’s mother, Ana, is Soviet-Born, and her father, Tony, is a Hong-Konger. Despite her international heritage, Ayn is afraid of both the sea and the sky and has never left Vekllei’s shores. Tzipora looks forward to spending part of the summer in Yana with Ayn and her grandparents each year.

III. Vekllei Fact of the Month #

Vekllei’s heavy diet of lab-grown meat, called ‘factory steak’ or eoui demanufacturie is so widespread in cities that many children in the capital region have never eaten meat from a living creature. Its texture and taste, especially after processing, is identical to beef and comes in different forms to replicate different cuts of meat, including fat and gristle. Most ‘real’ meat in Vekllei cities consists of sweetbreads, offcuts and organs — the stuff left over from authentic rural consumption of the prime cuts. Chicken hearts, for example, are eaten by themselves or on a skewer.

IV. WordBook #

Iyadaisnesn — also called “Insta-skin” is a collagen scaffold that rapidly seals and then regenerates skin over wounds. It is used medicinally in Vekllei, where it is branded as Iyadaisnesn, and is usually aerosolised and applied to shallow scrapes and grazes to seal the wound and prevent infection. Within a few days, it’s good as new! A type of Insta-skin is also used by the military, where it is distributed in wet pouches and acts much faster on much more serious wounds.

V. The Bulletin #

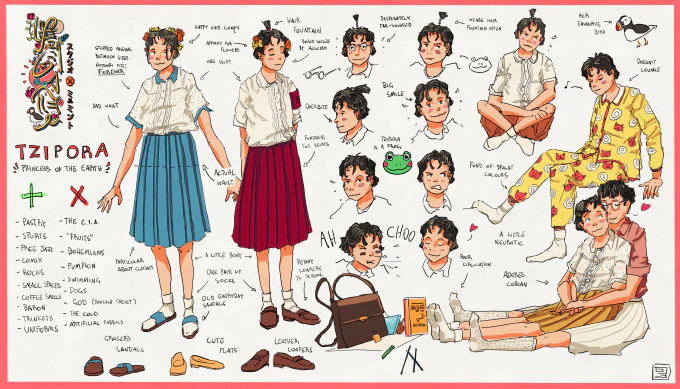

Meet Tzipora – concept panel for a Vekllei comic #

📖 Published 31st July 2020 | Read here.

There are a lot of things Tzipora does differently to everybody else, and they start to make a lot more sense when you realise Tzipora either does not realise she is unusual, or does not care.

She has a lot of endearing characteristics that give great character to her mannerisms and physicality. She has a small overbite that makes her look a little froggy, and ritually pulls on her shirt and wipes her nose in anxious conversation. She is round-headed and cuts her hair herself. She talks in a low, expressive voice. She has been poorly socialised in childhood, and is afraid of casual conversation with people she does not know. She is keenly socially attuned and feels awkwardness painfully.

She wears the same clothes two or three days in a row. The outfits themselves are variations of the same thing, and her tastes don’t change. Everything hangs off her — she likes baggy, airy clothing, and upsizes to accomodate. She doesn’t like fashionable or voguish people, whom she regards as decadent and offensive. To Tzipora, taste is timeless and bound to the soul. In her case, this fact has held true — she has dressed the same as childhood, and very little else has changed about her in that time.

She is paranoid and conservative, good-natured and austere, with a moral outlook bound by her deepest anxieties and obsessions. She is deeply spiritual and material, fascinated with objects and their history. She has many collections of many things she’s found. She’ll likely die a Catholic, but has a confrontational relationship with God and no longer attends mass, as a declaration of humanism. She does not know if this has pissed Him off, but it’s working out so far. Maybe that’s why He made her a homosexual — to get back at her. He must have a good sense of humour, if that’s the case.

Tzipora may be intense and inward-facing, but she can also be disarmingly charming and self-deprecating. She has a good sense of humour. There are not many girls that can so easily reconcile the contradictions between the peculiar and the healthy, the eccentric and the friendly, and the violent and the domestic. That’s part of her character — an essence of being that radiates decency, good taste and a respect for the spirit of all things.

Summer House in the Azores #

📖 Published 28th July 2020 | Read here.

The Azores had been a possession of Vekllei since 2002, when they were leased from Portugal indefinitely. The lease was defunct by the time of Vekllei’s independence from U.K. occupation in 2015, and the new state took formal ownership over the small Atlantic islands.

The Azores was Vekllei’s resort region, often called simply the “holiday isles”. Brief reprieves from the North Atlantic cold were granted to hundreds of thousands domestic tourists each year in resorts and holiday rentals alike. Tzipora spent the summer of 2079 there. Good memories were made in that summer. She did not much like the beach but she liked the ocean. If she could retire, it would be in the Azore

Base Camp #

📖 Published 21st July 2020 | Read here.

Just a paint-sketch.

The puffin scouts set up camp not far from the rest, just outside of Krafla in the Lava region. When they moved south tomorrow, thick native grasses and trees would give way to flower-tundras and bare hills, and by Tuesday they’d be in the heart of Lava — empty and extraterrestrial and volcanic.

The Krafla high-energy communications tower was visible from all over the region. It provided uninterrupted radio to most of North Lava, and could relay signals through satellites. In another country, it might have been considered a blight on a pristine view — but in Vekllei, there was no such thing as pristine. It was as much a part of the landscape as the trees.

They started the fire first, figuring they’d have more enthusiasm for the tent when they were warm. Warm sunrays played on the field-grasses around them.

Tzipora’s ‘Every Day Carry’ #

📖 Published 20th July 2020 | Read here.

Like a lot of girls of poverty, Tzipora was very possessive of her things. No food was ever left on her plate. There was a deep anxiety that whatever wasn’t claimed would be lost. She was also naturally obsessive and material-oriented, keenly aware of the importance of objects measured by metrics in her own silly head. You can discover a lot about a person from their trinkets and toys — let’s discover a bit about Tzipora.

-

Her handbag is manufactured by Spaa S.p.A., a design firm in the capital. They’re a luxury item in the international market but readily available in Vekllei, since few other handbag makers operate on the scale of Spaa. Ayn picked it out shortly after Tzipora’s arrival for its colour, after Tzipora told her she did not own any red things.

-

Tzipora has a sweet tooth. Especially for soda, which she calls “fizzy drink”. On her person at any time, she carries a flavoured beverage from one of several brands capable of meeting her discerning tastes. She supplements them with a water bottle, since not even fizzy drink refreshes as well as water after phys-ed or a hot day. She also stocks her arsenal of snacks with good fruit picked off trees that overhang footpaths, as well as devastating salvos of Vekllei’s finest confectionary, including Fruit Tingles and chocolate pearls. Other girls in her class bemoan her childish metabolism as she drinks soda for lunch while they watch the scales.

-

The nostalgic whimsy of the sweets is tempered by two or three loose cigarettes that float around in her purse at any given time. She’s not a regular smoker, but she’s prone to attacks related to stress, and nothing helps as much as a drag. She carries matches, for not much reason other than that’s what Baron uses, and Tzipora is notoriously sentimental.

-

Tzipora has a rock collection that sits on her bedroom sill, and her recent additions sit at the bottom of her purse. She’s not a rock elitist; quartz from footpaths catches her attention as easily as igneous treasures like palagonite. Her favourite is obsidian.

-

She carries a small collection of useful books, including a contemporary paperback and a notebook. The paperback is for recess and lunch; the notebook is for language notes and phone numbers. Her Vekllei I.D. papers, which are both a passport and a reference booklet of key information and services, are carried on her at all times. It’s not really necessary in day-to-day life — but who knows when it might be, and Tzipora won’t be the one patting her pockets at the airport gate.

-

Finally, there are a few accessories sitting in the bag. Tzipora made a ring for Cobian in metalworking class, but Cobian is on a school trip to France at the moment and Tzipora is waiting for her return. She has a wristwatch given to her by Baron, which she wears sometimes depending on the occasion. Other items are more precautionary — a scarf for the wind, a handkerchief for sneezing, and a spare pair of socks for when she visits Cobian’s house or if she needs to double up in cold weather. As summer turns to autumn, she also carries gloves and a beanie.

With everything in its place, her handbag is her anchor in the world outside her small second-floor apartment. The decommodification of society has only intensified the social value of objects, and they remain as important as ever in the life of the ordinary Vekllei person.

The Race for Inefficiency: Vekllei’s advocation of austerity, apathy, and playfulness as economic principles #

📖 Published 13th July 2020 | Read here.

Overview of the Bureau System #

There are many thousands of companies busy with work in Vekllei. The vast majority of these companies are single-person shops (S.p.A., or senrouiva pettetie anaproiouya). Also common are wobbly shops, or co-operative businesses (S.q.A., or senrouiva qualitie anaproiouya). The largest of the non-bureau companies are village factories (S.p.M., or senrouiva persimonaya manufacturie).

The bureau-level world is full of company mastheads that emphasise modernity, dynamism and progress. Vekllei’s “private businesses”, however, tend to be local in taste. The vast majority of S.p.A. and S.q.A. businesses bear the family names of their founders — Desmesyo S.p.A., Risyiouisnesn Home Machines S.q.A., etc. Their legal denominations are almost always affixed to the end of their nameplates.

Their senrouiva designation marks them as non-bureau businesses. A bureau, as a reminder, is simply the top-level organisation of a trade union that organises business in the country. In practice, it means that a company is responsible to the political organs of the country. Although independent from the government, bureau business is inextricably entwined in government concern and runs parallel to it.

Senrouvia businesses are also part of the bureau structure, but are in practice not managed directly by them. They are usually united in local concern by so-called petty bureaus; small cooperative organs that safeguard local interest and business. These petty bureaus are often at odds with the bureau organs proper, and so even though they are part of the same structure, they are fundamentally political opposed.

So what is sort of business goes on in a bureau proper?

There are two common categories of so-called “bureau firms”. You have state industries (S.A., or societie indastrie), which deal with manufacturing and exploitation of resources that require direct management by a public organ. You’ll already be familiar with several — General Reactor, Comen Aeroyards S.A., Farmer’s Syndicate S.A. to name a few.

You also have state requisites (A.r., or requoisesiasn amourisocietie), which refer to the vast government-operated organs made up six categories primarily.

- Utilities (A.r.Un.)

- Transport (A.r.R.)

- Education (A.r.E.)

- Local healthcare (A.r.F.)

- Construction (A.r.Lo.)

- Automation (A.r.M.)

Yes — education is not organised as a government department, but a bureau business. Other state responsibilities are folded directly into government departments — war, intelligence, healthcare, police, fire, and the mint are all managed directly by the government.

Argument #

With the legal division of enterprise laid out, let us examine again the four precepts of the Vekllei economic ideology.

- Self-management and self-interest through Sundress Municipalism.

- Classification of property as an independent social organ, like nature.

- Abolishment of currency and currency-substitutes. Participatory employment.

- Economic feminisation.

These four principles reveal a great deal about the character of the country, and stand largely at face value. There is an interest in chasing the promises of modernity while deconstructing its metaphysical constructions, through the abolishment of exchange-value, property and the overhaul of gender-economics. There are anarchist gestures in each principle, yet it is obvious that the product of these values complexify the conventional anarchist imagination. This is part of a series of contradictions — between free and planned markets, between internationalism and provinciality, between man and woman, between freedom and security.

Austerity #

The bureau system is plagued by inefficiencies, arising from logistic systems premised on warehousing, poor Coasean bargaining between petty bureaus and proper bureaus, a political emphasis on macroeconomic outcomes, a decoupling of aggregate demand and national economic output, cultural intolerance for Pareto inefficiencies, etc.

Luxury goods often vary in both supply and access, and economies are often severely localised to the point of provincialism, meaning that Vekllei has failed to transition reliably to a modern consumer society. The inhabitants of the Montre borough most often eat seafood because speciality meats, especially authentic red meat, are scarce. The opposite is true in Yana. Clothes are repaired and regifted, appliances are available only from regional outlets usually located in the same city as the factory, and culture and diet are fiercely regional.

This is, in part, a result of unflinching national austerity and the sublimation of artificial markets prompted by Vekllei’s gold-based auxiliary currency, which necessitates meeting debt obligations for its strength internationally. There is a belief in Vekllei that the wealth of the country allowed the abolition of the currency — in fact, the opposite is true. The abolition of currency allows a permanent wealth that compensates for the inefficiencies of the bureau system. The bureau firms do not pay their workers — on paper, there are no expenses for anything beyond raw commodity exchange. This is how Vekllei’s largest companies — and, per the bureau system, its government — remain solvent.

Austerity is a cultural force, too — the scarcity of luxury goods inflates their social value, where comforts and necessities are largely abundant in automation. It creates an unimportant hardship that keeps Vekllei people forward-facing, lean, and ambitious. To acquire Picco S.p.A.’s iconic lounge chairs, you have to travel to their outlet in Horn, hundreds of kilometres from the capital area. There is no motivation for a craftsman to meet demand — there is no petty consumption, either. To own a Picco chair means you have understood its cultural value, utility and craftsmanship, and have made the effort to find and transport one to your home. Inconvenience, and by extension, austerity, is celebrated as a “trial of ownership.” Objects are very important in Vekllei, and craftsmanship is highly valued, and so people like to surround themselves with hand-made, sublime things wrought not just by the labour of the artisan, but their own effort to acquire it.

Petty austerity instills a national sentiment that tells the ordinary Vekllei person they are hardier than the ordinary American or European, even if the wealth of the ordinary Vekllei person is much greater than that of the ordinary American or European.

Apathy #

Despite a vast, loosely organised private market in the senrouiva categorisation, Vekllei does not reward entrepreneurial ambition. Ambitious people are funnelled into positions of power in bureau firms and political office, but the founding of S.p.As and S.q.As is rarely motivated by a desire for influence or power. Indeed, artisanal S.p.As are often incapable of the sort of economies of scale needed for expansion. Vekllei instead relies on a sort of economic apathy, in which aggregate demand and productivity are spurned for immediate interest and pleasure.

This ensures that

- luxury products remain creative, personal works per Upen’s insistence on the symbiosis of labour and product

- the private senrouiva market is not capable of threatening the provincialism of Sundress Municipalism, which might make a commodity universally accessible and threaten to introduce generic consumer society into Vekllei life

- the private senrouiva market under petty bureau organisation does not threaten the organised de facto monopolies of the bureau companies

If Vekllei has replaced the commodity with the object, then it is through economic apathy that they have ensured objects will never again become commodities. Just as the ordinary Vekllei person is apolitical, so too are they apathetic towards change in their purchasing habits, favouring small, inconvenient and personal brands over those exploiting aggregate demand. In a sense, this also contributed to the popular Vekllei term product atheism, in which the metaphysics of products are dismantled and rearranged into social forms.

In this sense, the apathy is found on both ends — within the senrouiva business owner, who is provided little upward mobility to satisfy ambition beyond local and regional expansion, and within the consumer, who recognises products only within cultural and social dimensions. Neither is conducive to a functioning, fair market on an interregional scale.

Play #

Play is the foundational motivation of most work in Vekllei. There are existential motivators, too — a desire to wield power, or professional legacy — but in many professions it is play by which a Vekllei person justifies labour. It is also why work is fiercely protected by petty bureaus and other labour organisations — work is their connection to wider society, and that connection is held sacred in Upen.

It is through work as play that Vekllei is able to justify the employment of children. Financial motivations for work have all but disappeared — in its place, the workplace has to convince people to work. There are few state protections for businesses unable to maintain a workforce, either — it is one of the most common reasons for the shuttering of a company. The boss must convince his workers to stay, and so a total inversion of power has occurred.

In place of money, there is prestige, and in prestige there is myth. Few people have genuine interest in Fordism. Many more are attracted to the hand-crafted furniture of Picco S.p.A., and becoming recognised as a builder of great things. In a sense, a person “acts out” the role of a craftsman, in the same way a person “acts out” the role of a police officer, or “acts out” life as a pilot.

In this system, the childish spirit of recreation, duty and “the adult world” is acted out by millions of Vekllei people each day. Seeds planted by a child play-acting as a farmer continue to grow, and so too does the Vekllei economy feed its population through the intersection of fantasy and labour. At this point it is obvious that play is not fantasy at all, but in fact a motivation for labour as genuine as profit. Where it falls short, in hard, disempowering jobs, it is automated and conscripted through the mandatory service system. As it is often described:

“The Bureau System is labour-intensive where wanted, alleviated by industrial machinery where preferred, and automated where necessary.”

In its wake are states of play, and through play comes a decent framework for living, obvious in the basic satisfaction of the Vekllei people.

Police in Vekllei #

📖 Published 8th July 2020 | Read here.

There are two regular police organs in Vekllei.

- Fedecenoayan porits (national police, or venopor)

- Comoisniyan denporitsa (local police, or cosmopor)

A young venopor officer stands on the left, in the full street regalia they’re renowned for. Unlike cosmopor they often carry machine guns while on patrol and are stationed outside of government buildings, hospitals, train stations, ports, schools and any company managed directly by a bureau, which is a trade organ of national importance. They are special units of special purpose, and supplement the deficiencies of local policing through their training and tactical deployment.

They are police insofar as they protect and respond to their community, including through special tactics situations, but are paramilitary in their wider function as a defence force for critical infrastructure. This is reflected in their history, traced cleanly back past independence and the Atomic War to the royal guards and junta federal police of old society, which continue to be reflected in their uniforms and several other ceremonial artefacts, like swords and knee boots. Venopor is a complex organisation with many different purposes. There are street patrols, pictured here, but there are also intelligence units associated with HO/NI and by extension the military, as well as tactical response teams, bomb squads, search and rescue and most other specialised emergency units outside of the capabilities of any given local police station.

This is contrast to the cosmopor, a more conventional police outfit. A cosmopor officer stands on the right, in standard summer uniform. He carries a radio, revolver and rubber baton for the worst of his duties, and is embedded deep into his local community. Cosmopor officers traditionally visit and introduce themselves to each house in their beat, and spend far more of their time mediating, counselling and organising than they do making arrests. The autonomy of most Vekllei communities largely spurns petty legal proceedings, and so the cosmopor are a critical aspect of sundress municipalism, resolving disputes personally and taking custody of a person only when it’s needed. Most crime in Vekllei tends to be emotionally motivated — so it is in this domain that cosmopor navigate.

This makes the cosmopor especially powerful figures in a Vekllei village or township, but their duties are closely watched. While the Vekllei village may be autonomous, all officers in Vekllei are responsible to a division of venopor called “officer welfare,” or picosec, which operates autonomously to seek out incompetent or misbehaving police officers, no matter their jurisdiction or status. Where most business in Vekllei has very little in the way of professional behaviour or “work culture”, policing in Vekllei is held to high standards, and they are severely bound by traditions that have become codified as the country has grown. This is a time and place where the children of police often inherit the jobs of their parents, and the constables of a village often have roots that go back centuries. This often makes cosmopor very respected figures, and their successors and recruits are expected to work for that respect.

In a country that has done away with money as a measure of success, professional legacy is profoundly important in Vekllei. In this inversion of priority, teachers, doctors, pilots, constables and librarians are celebrated. This is not founded in a general egalitarianism, but in fact the precise opposite — a celebration of success and influence, touching the lives of those around them. The glamour, and paycheque, has largely been stripped away. Only the work remains, and so that work has become more important than ever.

VI. The Post Office #

Why you should love your computer: Independence and control through free software [NEW] #

BY MTIRADO#2460

Do you feel proud when you turn on your computer? Do you feel satisfied with your favourite software’s user experience? Nowadays technology, specially I.T., is getting more and more intertwined with our daily lives. Each year we rely more and more on it and at the same time, layers upon layers of abstraction are being placed to simplify its usage and impede our understanding of its inner workings. Social media, web services, software and devices that we use daily offer us an intuitive and simple experience at the cost of giving up any sort of control or fine-tuning. Take a look at computers for example — your average desktop or laptop. For many people, their computer is just another tool; a complicated, scary, cumbersome tool. Plagued with viruses, weird pop-ups, and painful slowness. If you dare to turn on your slow, noisy computer, it’s because you had to print some documents or fill out an online form. So you just open MS Office Word, and/or Google Chrome, and forget everything else, because clicking on any other icon will render your computer useless. Even if it’s fast and sleek, computers are still a mystery. Then, outside of our comfort zone, there lies the stuff of tech specialists, hackers, and hobbyists. Even if you’re a tech enthusiast that keeps up with the latest gadgets and updates, your user experience is still dependent on the decisions of a single organisation or company that does not usually tolerate decentralisation. We do not have enough control over the products we own.

Were computers always meant to be used like this? Like a black box that’s hard to open and understand — hard to make it ours? Mainstream operating systems and software give us the promise of an experience that just works — if we go all in on their ecosystems. Their software and utilities are easy to use and intuitive, but hard to understand and control. If you want to customize how your favorite program renders a different type of file, good luck with that. If you want to do something that’s slightly outside the program’s intended purpose, no one can help you. Future updates are controlled by a small, concentrated group. You can never know what goes on under the hood if you can’t open the hood. You can never know how something works if there’s no need to read the manual. These days, privacy concerns are greater than ever, and smartphones are getting harder and harder to tamper with, using proprietary software and assembly techniques that make repair difficult. We learn to accept and embrace the software that comes bundled with our computer and we shudder when we realise we need to fix a problem ourselves.

So what’s the alternative?, How are we supposed to strengthen the relationship between the user and the tool when we are told to accept that computers are hard to understand and control, and that abstraction is necessary? This is where free (‘free’ as in ‘freedom’), open source software becomes relevant. Open source software gives the user privacy, flexibility, control, and choice. A wide variety of open source software caters to the nerdiest of power users and the casual users that only needs to browse the web and print some documents alike. It doesn’t matter if you don’t know how to read the code. You don’t have to learn a programming language to be able to regain independence and control of your computer. Free software like Linux has come a long way, and is now more user friendly than ever. You shouldn’t have to choose between ease-of-use and open source software — and with Linux, it’s no longer a trade-off. Installing a new OS, tinkering with your machine, following tutorials to customise the UI, and making a website not only gives you have a deeper understanding of how your computer and technology works, it helps change your perception of computing and your relationship with technology in general. Using software that encourages you to modify and customise gives you control and independence that no proprietary software can.

I can’t promise you that you won’t face problems using open source software, because that’s simply not true. Sometimes we can’t leave proprietary software altogether. No software is perfect, just as no tool is perfect. But at least free software gives you the opportunity to make a better tool, if you’re willing to sharpen it, willing to read through the documentation, willing to work and get your hands dirty with configuration files to solve a problem, and of course, willing to fail. The reward goes beyond having your computer work just as you want it: you end up with a tool, a product that is truly yours — something you can feel proud of, tangible and meaningful.

Does that mean that we should struggle every time we use our computer? Absolutely not. But we shouldn’t always strive to make technology easy to use, but instead try and make it easy to understand. Because if you’re able to make sense of things and truly know what’s going on, ease of use will come naturally.

P.S. If you’re thinking about switching to Linux, my personal recommendation is Linux Mint. I recently installed it on a laptop and automatically detected Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and all network printers. No driver download required. It’s ready to use out of the box and highly customisable. And remember, you can keep Linux and your current operating system in the same computer if you want.

VII. Gallery #

This month’s sketches, presented without context or or standards of quality. The postcards will be included in the August edition. Contact Hobart at [email protected] for full-res versions of any images received in this bulletin.

Scrapped postcard [15.7.2020] #

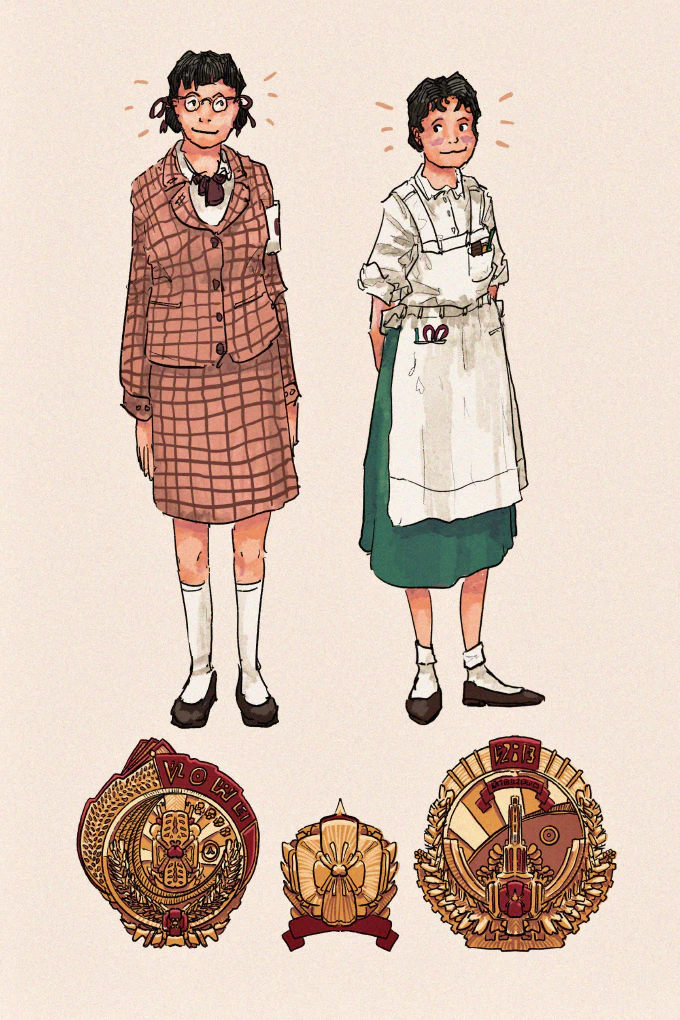

Tzipora and Baron [9.7.2020] #

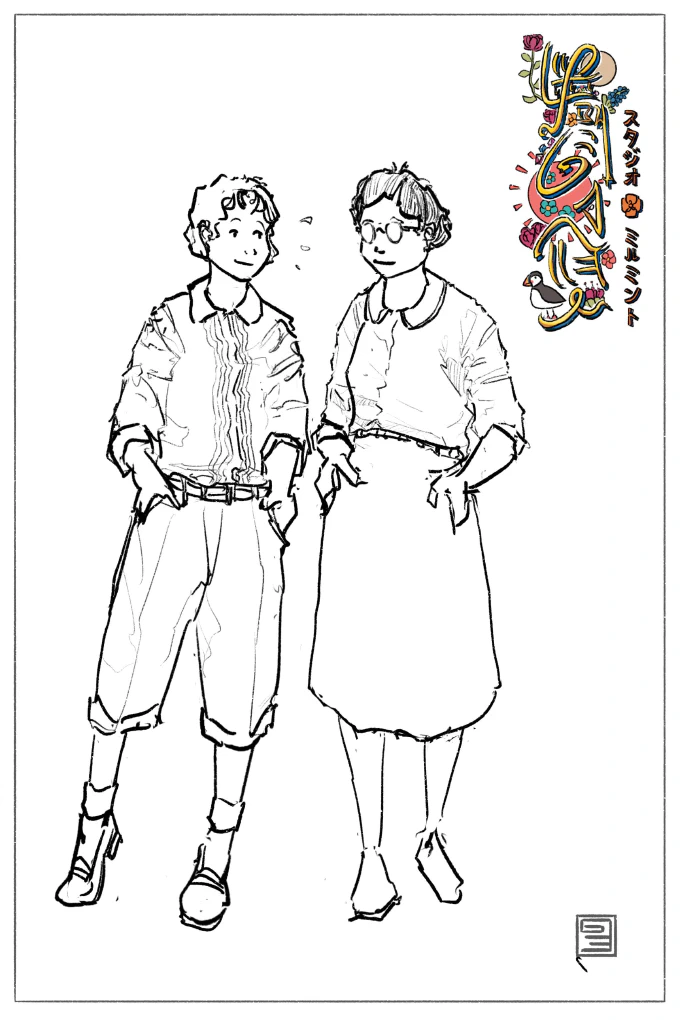

Untitled [9.7.2020] #

POSTS THIS MONTH: 6 #

POSTS LAST MONTH: 7 #

Published by MillMint Press. Copyright 2020. To stop receiving these emails send UNSUBSCRIBE to [email protected].