NEW Story: Sunday Morning

Winter Clothing (and Womanhood in Vekllei)

Welcome to Vekllei. It is a strange country with a complex culture that is quite distinct (and sometimes outrageous) to Western countries. This will be a long post. I’ve tried to keep it clear.

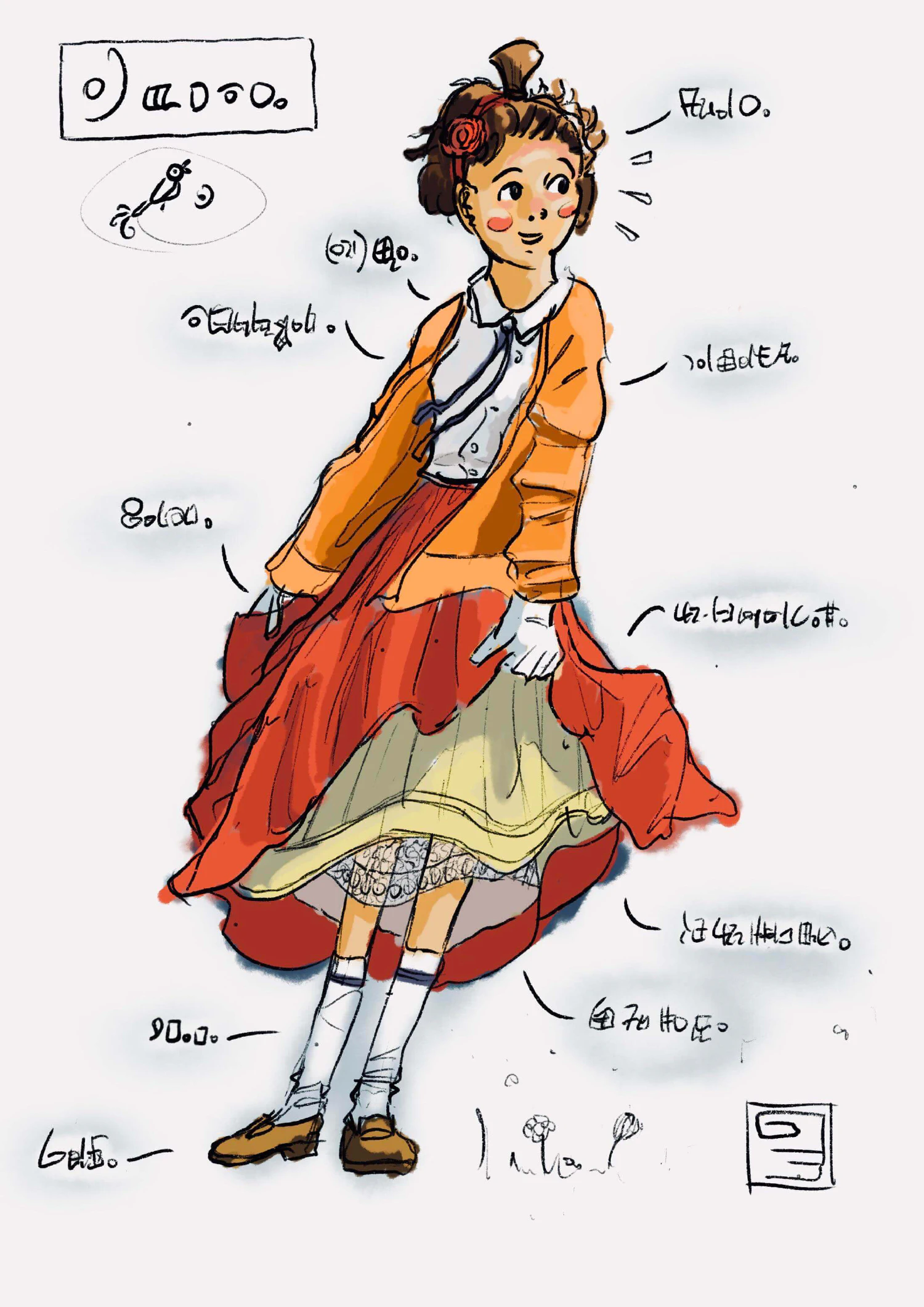

Women in Vekllei usually wear skirts in winter. There are cultural and historical reasons for this, explained below. Pictured here is Tzipora in a winter Vekllei outfit so typical it works well enough here to give a show-and-tell. The outfit consists of underwear (vest, stockings/socks, etc.), an inner lace petticoat, a cotton thermal pettiskirt, and a wool outer skirt. They reach about the mid-shin. She wears a thick cotton shirt over her vest and a rayon cardigan on top, with cotton gloves. Although not pictured here, when heading out a long wool overcoat would protect from the fierce Vekllei wind.

The colours are not wintery, but that requires context. The history of language and gender are not everyone’s cup of tea, but if you want to know more, let’s get started.

Winters in Vekllei are long and dark. In the depths of it the sun rises only for about an hour. Temperatures range between 5 and -15 centigrade. By all accounts it is not a place for skirts.

But many women don’t consider thick or multilayered trousers. This is because womanhood is tied very clearly to physical appearance. Vekllei lacks gender pronouns entirely, but has very clear feminine and masculine words. Vekllei written language is logographic, and so you ‘construct’ concepts out of images. So certain gender concepts, like femininity, are constructed out of feminine associations that ‘build’ a sensation and understanding of what it means to be female. Skirts are a part of that. To feel like a woman in Vekllei, there are explicit images that build femininity.

That is not to say Vekllei is necessarily misogynist, at least as we understand it through a Western lens — the political and cultural understanding of the country (usually called ‘petticoat socialism’) strongly suggests that our fundamental ‘human’ traits are inherently female.

It emphasises the overall ‘femininity’ of humanity and shifts the human core to female, and then distinguishes masculine traits as radical and far from the centre of the human condition. Petticoat feminism takes on economic qualities and a radical reading of gender to describe its main point of function and praxis — that masculine qualities are inherently economic, and that they will cease to be masculine as petticoat socialism achieves its aim of rendering labour unnecessary for all reasons except self-satisfaction. In petticoat feminism, the final form of the human race is female — not in a biological sense, but in a cultural attitude that has essentially ceased to distinguish between masculine and feminine qualities, while retaining what it views as inherently female virtues.

Fragility, grace, beauty, leisure, and reproduction are placed upon the shoulders of men, rendering them ‘female’ in the lexicon of petticoat feminism, and thus relieving them of the economic burden of masculinity.

Knowing all that, it still basically means that skirts are for women, and women wear skirts to feel like women. Vekllei clothing has thus become multilayered and insulated to adapt to the shift from summer to winter.

As far as colours go, Vekllei is volcanic and geographically active. Fire and ice are synonymous here. This means that red and blues are associated with keeping warm and ice, and yellows and greens are for the lush foliage in the warmer seasons. It is uncommon to wear reds in the summer — it’s too hot to need colours associated with fire.

This post is long enough, I think. Tzipora is in the wind but looks happy enough. If you have questions about the language itself, or what the annotations say, just ask.