NEW Story: Cocktail

Absolute Grotesque

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

✿ This article was featured in Issue #4 of the Atlantic Bulletin

On the morning of the second day, I watched a fly crawl across the cheek of the middle-aged woman, probably an office worker, lying next to me. It moved up her cheekbone to her temple, stopping now and then to rub its front legs as though performing a ritual. A jagged tear ran down the leg of her dark blue work trousers, but the white calf it revealed was miraculously unscathed. The woman lay still. Probably dead, I assumed. After a while, the fly got on to her eyelid. Suddenly, she reached up and brushed it away, opening the eye. There was still a moist light inside.

From Insects, by Seirai Yūichi

By chance, the glass paperweight had survived. When her in-laws’ house had burnt down in Yokohama, the paperweight was among those things that she’d frantically stuffed into an emergency bag, and now it was her only souvenir of life in her girlhood home.

From evening on, in the alley, she could hear the strange cries of the neighbourhood girls. Rumour had it that they could make a thousand yen in a single night. Now and then she would find herself holding the forty-sen paperweight she had bought after ten days of indecision when she was these girls’ age, and as she studied the sweet little dog in relief, she would realise with a shock that there was not a single dog left in the whole burnt-out neighbourhood.

From The Silver Fifty-Sen Pieces, by Kawabata Yasunari

On the 14th of August 2111, the Atomic War began in a Chinese submarine in the South Pacific, and ended six hours later. The war marks the single greatest loss of life in human history and would disrupt human life on Earth in previously unimaginable ways — consumer society bottomed out, the world became small, the Earth grew cold, and a new chapter in human history was opened.

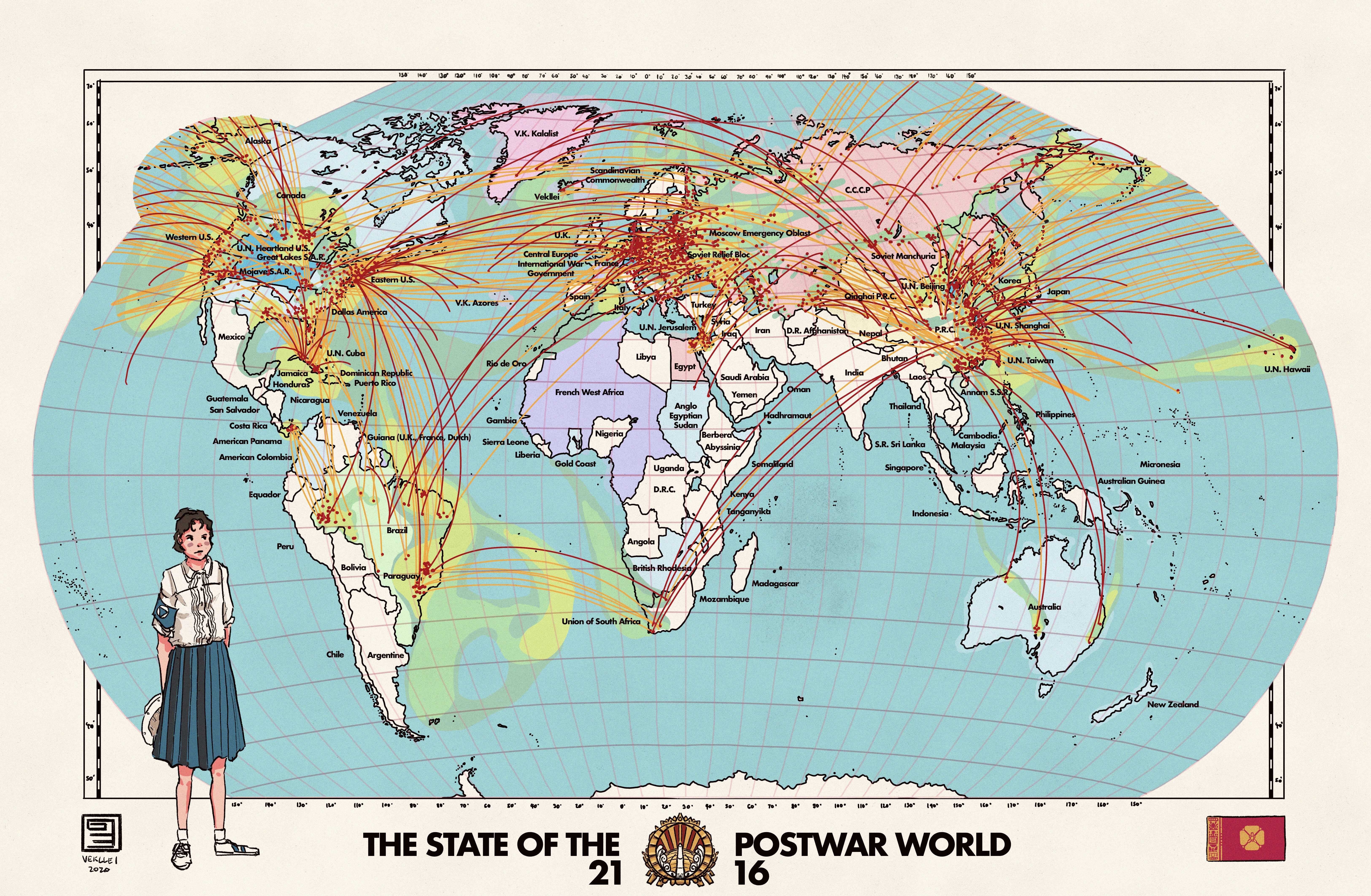

This political map marks the territories of Earth as they stand five years on, in 2116. There are fewer countries in the world today than in any other point in human history, in part because the catastrophic reduction in human population — some 520-600 millions in the first year — has emptied out countries and rendered others uninhabitable. Many of these territories here are disputed and, in some cases, autonomous — for simplicity, they are presented as they are recognised by the U.N. The map also presents a long-exposure view of the war as it happened, and its remaining fallout currents today. Red dots mark significant nuclear detonations on August 14th. Yellow dots mark surface warfare in some capacity. Red trails mark missile flight, reduced in number here by strict denuclearisation treaties of the decades previous. Yellow trails mark the flight paths of atomic bombers, both supersonic and subsonic. This map does not record failed launches, intercepted missiles or downed aircraft.

Fighting was arranged along political axes — namely Western (U.S., U.K., West Germany & N.A.T.O. members), Warsaw Pact (U.S.S.R., Cuba, Egypt), East Asian (China & Korea), and non-aligned (Vekllei, France, Brazil). The war experience was unique to each country — Vekllei exchanged warheads and bombs with China but not Warsaw countries, the U.S.S.R. exchanged with both Western and East Asian members, and Brazil fought a catastrophic war against both Soviet and American territories. The immediate aftermath saw a quiet Earth, much of it scorched. Temperatures dropped by 10 degrees centigrade for the first six months, and slowly warmed as debris cleared in the following years. Wide-scale firestorms were tempered by rains that followed the war shortly.

Some 274 millions of the dead are accounted for in China, where in 2116 the cities still lie in rot, swollen with corpses; heavy with miasma; concrete dams bleached and cracked; the wood all burned up; the rivers warped and quiet; dead fish along them; a surfaced water main weeping blood; harsh asbestine whistling; railcars in a ditch; sloughing skin; tremors; smoke with no fires; confused wandering; bleeding from the inside; families-as-sand; sand-as-trinitite.

Exchanges were confused, helter-skelter, and the combatants rattle off like a death snare. The U.S.S.R., the U.S., France, and Vekllei all exchanged death with China.

It would take more than mere annihilation to extinguish the P.R.C., but the toll was nauseating. Beijing and Shanghai were simply disappeared; there was nothing where there once was. The fistfuls of rebar and concrete amidst glassy, ossified landscape were heaped into direct administration of the U.N. The following year, 40-120 million more Chinese would succumb to the greatest famine in the history of the world. Of course, in the U.N., there was good argument for the nuclear retaliation — China launched first; why should money and food go to the perpetrator of the vastest disaster in human history? One can’t help but wonder if the life of an Oriental coolie wells fewer tears than his equivalent in Paris. There are not enough flowers in the world to pay tribute to the dead of China, who were simply dispensed with in European memory and subsumed in part by the United Nations. The communist party would continue to control the vast interior, divided into two states by ethnography, where 1949 seemed closer than ever. Necrotic politics are legitimised in the land of the dead. Soon, we saw the consolidation of nation-states into geographic regions with a disregard for ethnography not seen since the colonial years. This was met with violent resistance in some places — in others, locals capitulated to the extraordinary hyperreality of the postwar world.

The United Nations was quickly catapulted into the status of a de facto administrative world government in a last-ditch attempt to ‘freeze time’ as it were, in order to provide the superpowers time to recover from the scope of immediate devastation and prevent humanity from entering a long period of decline. This involved the moving of soldiers on a scale unseen since the World Wars, as U.N. international brigades propped up vulnerable, scorched territories in Central/Western Europe and Asia. The immediate peace of the first days after the war was ruthlessly enforced — and strategic opportunism was threatened to meet indiscriminate violence and U.N.-sanctioned nuclear retaliation. There was some belief that the status quo could carry on. So troops of non-combatant countries were supplied, and in some cases press-ganged, into this global mission.

The battered United States, acknowledging its ‘century of decline’, found itself consolidating control over its urban, though devastated, coasts. The awkward appellation “Dallas America” was used as a colloquial shorthand for a disputed territory that insisted on referring to itself as the legitimate United States. The name was only superseded by the ridiculous “United Nations Heartlands of the United States,” the Aid Region of the U.S. interior that had collapsed in the days after the war. This was buffered by the Mojave and Great Lakes Special Administrative Regions, federal territories that contained war industry and nuclear infrastructure that propped up the precarious coasts. Despite efforts to revive agriculture in the scorched U.N. Heartlands U.S., starvation was met with martial law along the coasts the following year.

The U.N. was granted temporary, direct control over several collapsed territories that had either succumbed to nuclear fire or had caved to anarchy in the weeks and months after. In some cases, like the U.N. regions in Hawaii, Jerusalem and the Central Europe International War Government, these behaved as states in themselves, administrated directly by the United Nations Mission for War Recovery. In others, they were merely named as such with the vague promise of future aid. U.N. Cuba and U.N. Taiwan were such examples, in which devastation had been so catastrophic that little remained to govern, and the local population was mostly left to anarchy. In general, there were great inequalities in how the U.N. chose to dedicate resources, largely informed by its largest nation-states and political interests.

There are thousands of stories from communities and territories across the world directly impacted by the war — from the atomic bombing of Sydney to the catastrophic reactor meltdowns of Brazil’s south. The war was unprecedented in scale and devastation. This map reveals little of the profoundly human tragedy that was brought about, nor does it invoke the difficult existential artefacts that are still being reckoned with. Perhaps humans are just animals after all — destined to die out the way so many have in this age. Most tragic was not the colossal scale of death, or the collapse and pain that followed, but the upending of domestic society into violence, in which people of consumer society — the middle class — found themselves with not much at all, thrust into a world of chaos and suffering in which all prior epistemologies evaporated. Like the flash of blue light that preceded the roar, it was the stuff in supermarkets and department stores that marked the absolute grotesqueing of life in the new age.