NEW Story: Sunday Morning

Making Trouble

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

Tzipora never lost her youthful curiosity. She would swish about the apartment, chasing an idea or plan that had occurred to her. Baron would look over and say “What are you doing, Zelda? Making trouble?” He said that a lot. He would come home in the afternoon and she would be writing lists, or organising her paperbacks, or moving furniture and he’d say, “What are you up to, Zelda? Making trouble?” She would say “No, I’m sending out invites for Christmas/learning the Dewey Decimal/going to have a nap in the sun.”

Zelda had a way of attracting trouble.

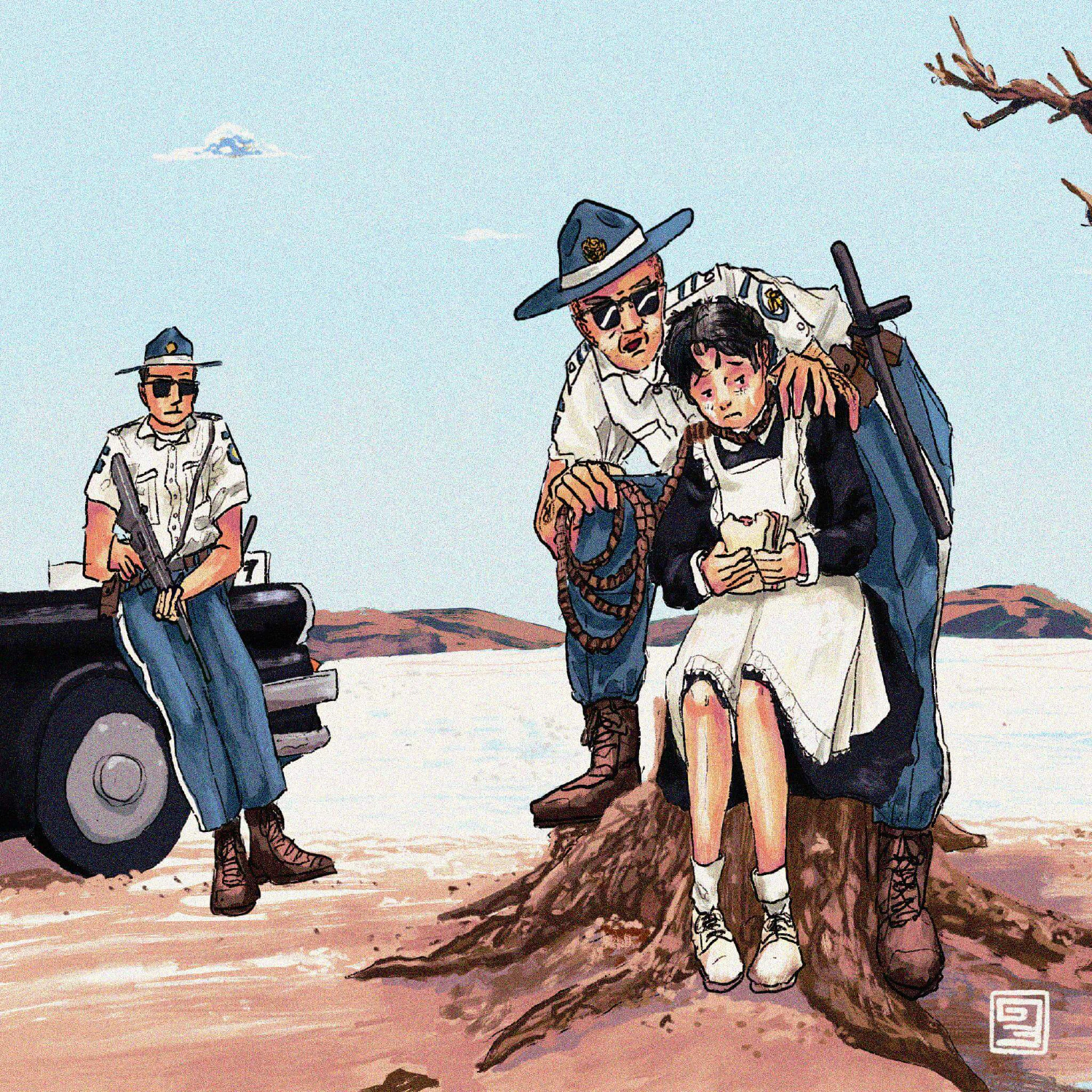

Two deputies dragged the maid who worked at Motel Grande off Route 70 to a tree beyond the Kennecott salt flats. She was crying the whole time. She was very young for a maid, but girls needed money like anyone else. She was starving. It wasn’t the kind of hunger you saw in the National Geographic; it was a long, slow year of starvation, where most of her muscle had wasted away and she’d been left with a bit of youthful fat around her belly and cheeks. That’s just how people looked in Utah in 2063. Atomic power collided with indigence across most of the Southwest.

This girl did not have a last name, because she was some immigrant worker with a fake visa worth less than her shitty hand-me-down rayon uniform. She knew what was coming in the back of the police cruiser and started to tremble uncontrollably as they left the highway. An immigrant expects what happens to immigrants. They pulled up by a stump and a small patch of dead ashes that were visible from the highway that crossed the flats. Would they take a picture of her for a postcard? She didn’t want that. Who would cut her down? Would they bury her? Suddenly the finality of it hit her — who, at all, would remember her?

She was not sure if she was being made an example or an excuse, but could not recall for her life what she’d done to deserve either. The car engine ticked over as the bigger of the cops slung a thin noose around her neck and yanked on it until it hurt her throat. She pleaded with them in good English, trying to suppress her Latina vocalisations, and cried desperately.

“I am American,” she whined, “I’m from California. Do I look Latina? Look, I’m white. My mother is from Germany. Please, you have the wrong person.”

“How old are you?” The big cop asked.

“Eighteen.”

“If you start fuckin lying I’ll string you up now. Tell me how old you are.”

“I’m sixteen. Sixteen,” she coughed. “I’m just a late grower. My father’s from Salt Lake. Please, I’m not an immigrant. I was born here. I’m American.”

“Shut up; I don’t give a shit. You live with some girls in town, right? In that house?”

“In downtown Cherry, yes. Yes, I’ll tell you about it.”

“And you work for Mr Parker at the motel?”

“Yes, I do. He’s nice.”

“Do you pay union dues?”

“Dues? No, I don’t think so.”

“Do you pay any tax?”

“It’s all cash,” she blinked tears out of her eyes. “I don’t know much about taxes.”

“All right, Griselda. We’re going to talk about some of the girls in that house.”

They asked her some questions and took some notes. What she was doing only occurred to her after the third name. They gave her a sandwich to eat. It wasn’t out of kindness — it was to bask in the absolute violence of their authority. You could find as much pleasure in pardoning a girl as you could beating her. For a moment, on their command, her poverty and fear was excused. She chewed through bologna as she listed out her neighbours, and after a while her tears were for them.

When she was almost done she began to wonder again if they’d kill her. She’d finished the sandwich and was unconsciously picking crumbs off her uniform, squishing her fingers pathetically against her lips as her eyes darted nervously between them. They left her there, with the noose around her neck, beneath the dead ash.