NEW Story: Sunday Morning

The participatory economy of Vekllei

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

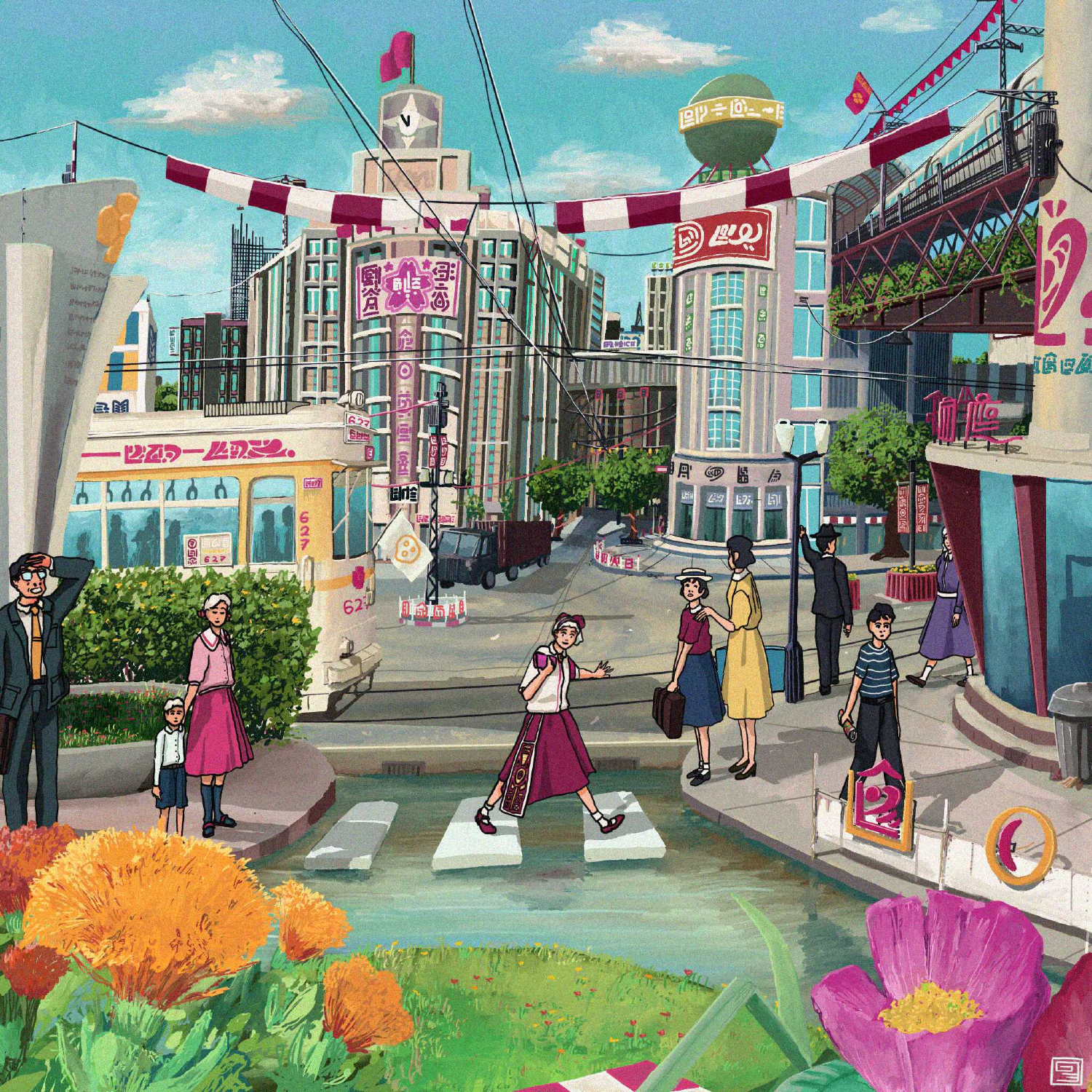

Nestled between the regional tram offices and the pre-war Ferouistet Department Store, the Lola district is not known for much but her department store and good schools. It sits on the slope of the wide Vekllei capital basin, where the Atlantic can be seen from the street. It was Tzipora’s first home in Vekllei, and it was where she lived with her father. The schools were good, the kids were all right, and the trams were a gift from Christ.

Most of Vekllei looks like Lola, marked by her mid-rise streets and public thermal ponds and geyser baths (named after the Vekllei village of Geyser, as it happens). Vekllei people do not generally own cars, and mostly commute via the metro, the exhaustive tram network or on occasion in a loan car from the autopool. The streets are narrow and empty of traffic save for service vehicles, and in the summers they are invaded by neighbourhood children playing baseball or seeking shade under the street trees.

Lola is one of hundreds of neighbourhoods in the vast, densely-populated capital of the country from which it aquires its namesake. It is a city facing its past, now that there is plenty to eat and little to do – and as a sprawling urban utopia with a fierce nostalgia for preindustrial life, there is no other place like it on Earth. Caught at once between the future of space and helijets, and her collective memories of agriculture and simple labour, Vekllei’s petticoat society marks a departure from futurism and a turn to its history, as though the violence and suffering and chaos of the past three centuries were but a chore obstructing utopia.

Participatory Economics & Property #

In Vekllei’s feminised parpolity, the revitalisation of Upen brought about an ancient understanding of property reborn in the widespread poverty of Vekllei society following the first Atomic War. Widespead social regression and cross-generational nostalgia for preindustrial life took hold in urban Vekllei society almost immediately after the atomic fire, as the ruins of colonial and imperial society lay around the Vekllei people. The monarchy, a tokenistic and fashionable invention of the gilded Mercantile age just three centuries before, evaporated nearly overnight with the death of the king. So, too, did the military junta salivating over the charred remains of the capital find it nearly impossible to consolidate power in a city now without infrastructure. In the ashes of modern industrialisation grew tempered, atomised communities of streets and villages — the common council as we see it today. Food production returned to the city in the ruins of vast factories, wide canals were dug for unmotorised barges, and councils of working people organised self-interest in these communities, which would be understood a century later as Sundress Municipalism. So too did the common understanding of property evaporate.

The old libertarian bugbear of the origins of property was revived — the population had been decimated, Vekllei people were surrounded by vast swaths of useless land of deceased ownership, and the institutions of old society had failed to retake power following the war. The question of ownership was pertinent, as it would clarify the sovereigns of future society. The sovereignty of Vekllei, as it would later be determined, is decentralised and portioned between any land-operating individual, local organisations, municiple councils, and syndicates. This tradition carries on today. In any one apartment building or row-house, you will find the inhabitants, building administrators, local councils and tenant unions exercising types of ownership over a space. In other words; residents of a home will have implied ownership over a home, but a community has implied ownership over the community itself. The intersection of different kinds of ownership result in complex and partially uncoded laws that, although vulnerable to beaurocratic and exhaustive legal disputes, are mostly discarded in place of local opinion.

The foundation of the Vekllei political and economic system is the community; a population larger than a single family and small enough to have valuable social bonds; a group of people bound by common living, work, and recreation. An unruly or criminal tenant is more likely to be run out of town by his neighbours than by the courts. This is not to misrepresent the daily conflicts of Vekllei domestic society — disputes are common and meaningless. But abuse of common ownership is tempered by the fact that it is quite impossible to evict any individual from his home without overwhelming agreement of his neighbours, essentially relegating formal council ownership to irrelevency; the true owners of any single home are, in practice, the community in which it is situated, supervised by protections offered under the local judicial councils.

The ownership of a factory is a lot more straightforward — the old mantra of the democratic workplace is more or less true here. Principally, unautomated (manned) factories recieve production requests from one of the hundreds of different economic bureaus keeping stock of production in the country, which otherwise do not directly supervise production except in circumstance of scarcity. Production requests are voluntary, and usually formalities in the production of items for local consumption. Heavily centralised industries, particularly heavy industries like raw product extraction and refining, usually operate under direct supervision of a bureau. Unions exist independently of the bureau system and usually hold membership from every worker of a factory, including managers. Mirroring nested councils, there are also larger industry unions that generally involve themselves only in general strikes and legal cases without precedent.

The ownership of a grocery store is clear and implied, if not codified. The person who manages and works the shop, either through implied property bonding (so-called ‘folk morality’; a phenomena largely dependent on the person’s social value and local consent) or familial tradition, owns the shop. These are not lawful protections of ownership — indeed, Vekllei common law says very little about senrouive business ownership — but in almost every case, they are validated by a community intuitively. Even antisocial or hostile shop-owners are rarely challenged on their right to the property they manage — the shop is, technically speaking, seen as an extension of the natural landscape (as no more than fired clay and timber), and the live-and-let-live culture in Vekllei is sympathetic to leaving people to their business and shop elsewhere. Legal disputes on the right to live above and manage a store are relatively rare, and usually resolved through ‘blood rights’ ( similar to ‘folk morality’) in the case of an individual or in a more democratic fashion involving multiple relevant complainants, like employees. In both of these examples, the disputed property is considered an entity itself with its own rights and interests extrapolated from its history and surrounding landscape.

Herein remains the distinction between venrouiva/senrouive property, and their implied ownership. Venrouiva usually operate in cooperation with the product bureaus in the case of manufacturing, or other national organisations as their industry requires in education, medicine, power, water, etc. They are ultimately beholden to the direction of the country, as organised by the seats of power and politics. Senrouive exists somewhat independent of the economy entirely, recieving mostly what it asks for and immersing their respective economies in the communities around them. Although all physical material in Vekllei is ultimately property of the country (a vague, naturalistic construct seen as distinct from the government, at least in a Western understanding), senrouivewill almost never be managed directly by larger unions or administrative bodies. This distinction does little to articulate public and private ownership, as the very concept of property remains formally unacknowledged in the economy in the country. Instead, all business today is conducted in cooperation with the ideas of community, implied ownership, self-interest and some sort of idea of supply and demand largely usurped by post-scarcity and widespread automation.

Because of this, Vekllei does not actually consider itself classless — Indeed, venrouiva are fundamentally a coordinating class of workers that are atomised from senrouive work through their power and decision-making. They are a class of power in law, education, science, medicine, and politics, and consequently, guide the direction of the country. Although even senrouive business is still fundamentally worker-owned and managed (as part of Sundress Municipalism), this hierarchy remains in principle, even if the quality of life of venrouiva and senrouive workers is in practice identical. This fact is rarely acknowledged outside of technical circles in the country, because it matters very little to the common Vekllei person. Vekllei is not outwardly egalitarian, despite practice, and the problems of power are mitigated by a mess of democratic structures ultimately enslaved to self-interested, independent communities of people. For one of the most centralised countries in the world, with a homogenous ethnic people and culture, Vekllei is better described as hundreds of thousands of hamlets than a single city.

this section is continued on my website: www.vekllei.city. It’s too long for reddit, and so I’ll continue work there.

you can check my reddit profile (and there’s a follow button there now, because reddit is Facebook) for more posts about Vekllei and Tzipora.

www.vekllei.city or insta fer more. I love questions. tahnk