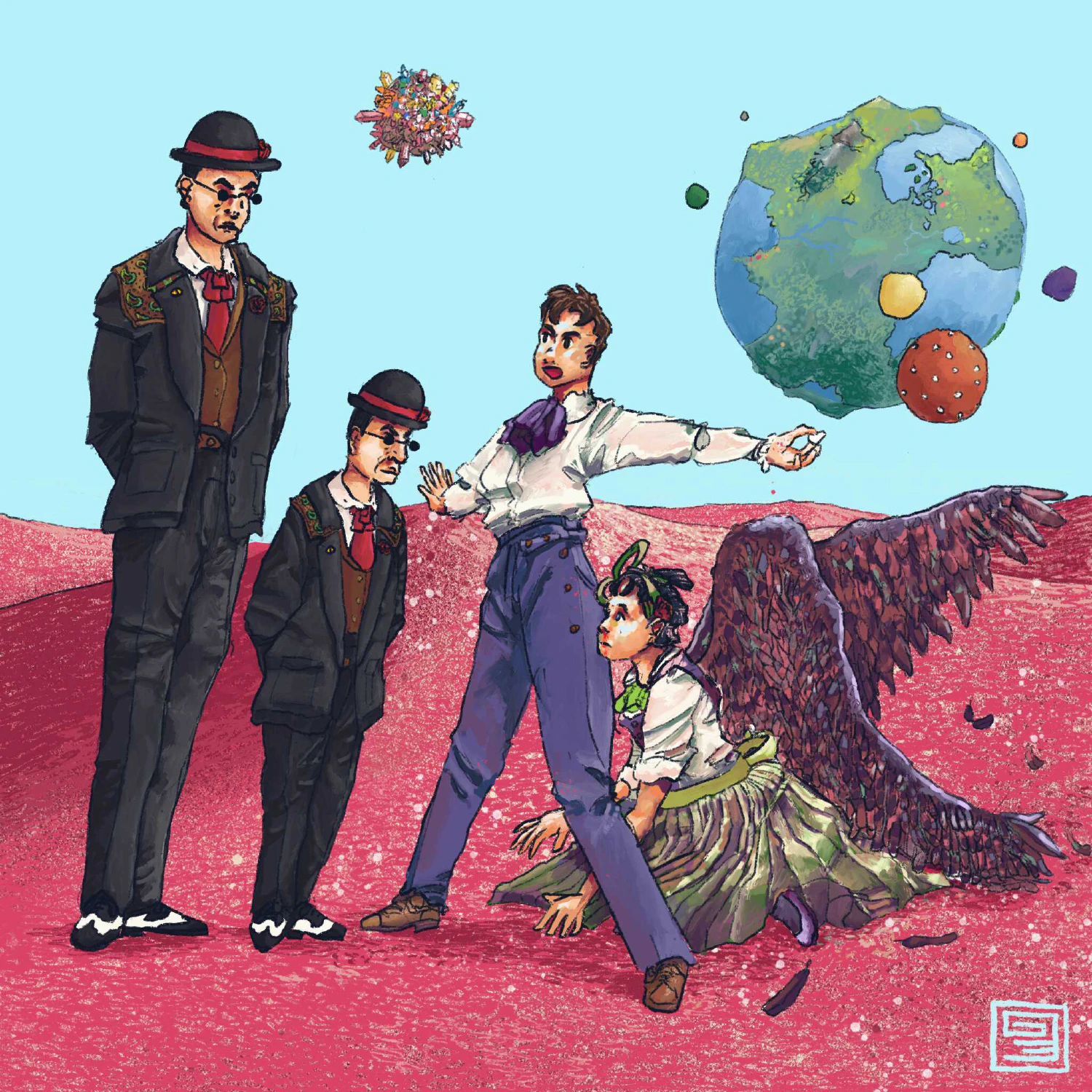

NEW Story: Sunday Morning

The Palace Gods attempt to retrieve their runaway child

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

She could feel the wind rising. The horizon beyond was warped, caught in the distortion of a forested planetoid before them. The morning sun cast a honeyed warmth on her wings of black sugar, which sang like wind chimes as she soared high above the gem deserts below. Hyssop, her new and only friend, followed her ungracefully under the spell of his flystone.

A chill caught her skull and traced her veins to her stomach, where it seized up. She felt the strength go from her wings and the world tilt out of focus. Her body plummeted, her figure limp, and Hyssop yelled out at her, “Princess! Tora! What’s wrong?”

Her wings trailed her as she fell from the sky, and he dived after her. The sparkle of the sand blinded them as the gems rose into view. They hit the dune in a plume of rubies.

She awoke and emerged from his arms. He was beneath her, dazed in the crash.

“Hyssop!” She screamed. “Hyssop, I’m sorry! Wake up—!”

She cried out again when she noticed two men in fine suits watching over them, like kites and carrion. Hyssop was wrenched from his dreams by her scream and scrambled to his feet. He turned to her seriously.

“Don’t move,” he told her calmly. “Don’t talk to them. Don’t even look at them. Just watch the flystone in my hand, Tora. Look at my hand and the sky. Look, the planetoids are out in their brilliance. Look at their oceans, Tora.”

She looked over the shoulder of the dune and faced the planetoids, but her thoughts were with him. She could admire nothing in her fear. Her knees and palms were pitted with gems and wept blood.

“Hyssop,” she whispered from the corner of her mouth, her face in the sun. A whimper caught in her throat and it coloured her voice. “What are those men?”

“Henchmen of the Palace Gods. They’re looking for you.”

“I’ll kill myself, before I go back. I belong among the living.”

“No-one will do anything,” he said. He sounded undisturbed. He reached behind himself and felt out for her hand, and she seized it and held it tight to her.

“Don’t acknowledge them,” he said, staring the henchmen down. “They are not among the living. Do not speak to them, or you’ll bring them here.”

“Okay. What do you want me to do?”

“Look at the sky. Think of us in Rose, by the sea. That’s where we’re going, when we leave this dune.”

“I’ve never been to the sea,” she said. “That’s where you said you were from, isn’t it? Rose?”

“Sure, Rose.”

“I’ve only seen it from the heavens. I want to see it as a girl.”

“You’ll see it. We’ll just have to wait for the henchmen to be recalled, first.”

Princess Tora, Part II, Pachinki Codex

-– The following is an excerpt from the book Outside Looking In, as prefaced by media analyst and outsider art historian Roy Tesmein.

The author herself, Tzipora Desmoines, would usually describe the henchmen of the Palace Gods as ‘Pinkerton’ — a sort of brutal thug for hire that dealt with asset retrieval and strikebreaking. Of course, the henchmen come from the heavens and are summoned for singular purposes, usually surveillance or sabotage. Tzipora was always very clear on the limitations of the Palace Gods, and their struggles to enter the mortal world, a weakness that inhibited the successful recapture of their runaway princess, Tora. In fact, Tora’s ability to enter the mortal world without the collapse of her mind, as dictated by the schism between planes, was more shocking in itself than her youthful betrayal. In many ways, Tora is a self-insert that witnesses much of the tragedy Tzipora had to come to terms with and rationalise in her early years in the American South. In this context, the Pinkerton moniker makes sense in Tzipora’s mind — just as Tora later attempts to organise Pachinki into a revolt against the Gods (with brutal suppression on the part of the henchmen), Tzipora herself witnessed bloody strikebreaking several times as she rode freight trains on Southern Pacific, a freight company that experienced violent industrial action shortly before its bankruptcy.

And further;

So Pachinki occasionally lurches into horror otherwise incongruous with the sweet fantasy Tzipora shows such affection for. Pachinki may be a world of peace and wonder, but just like Tzipora’s own present utopian surrounds, it belies a historical context of starvation, mass graves and political violence. Part of the wonder of Pachinki, looking back, is that Tzipora seemed keenly aware of the prohibitively dark nature of this kind of violence in her otherwise escapist whimsy, and this maternal turbulence with her own work is so obvious that even the most casual reader will be conscious of its inconsistency. A page about the pleasure of tasting fruit gems will pirouette into musings on the use of slavery in their procurement and the sabotaging of their production to justify conquest and war. The surreal dissonance of her own motivations for creating Pachinki reflect a girl who was herself living a surreal, contradictory existence — at her time of writing, she was living in a land of plenty and peace, where just a year before she was nearly killed after grocers in Cherry started poisoning their food waste to drive away homeless and vagrants. Her own existence was one of startling contrast — a rapid transition to petticoat society from the misery of the American South, where she witnessed indiscriminate slaughter, sexual violence and crippling poverty. Whatever hurts is real, and so Vekllei did not feel real to her — and consequently, Pachinki is suspended in the same internal turmoil.