NEW Story: Sunday Morning

A Map of Vekllei — 100 Boroughs; 100 Hearts

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

✿ This article was featured in Issue #2 of the Atlantic Bulletin

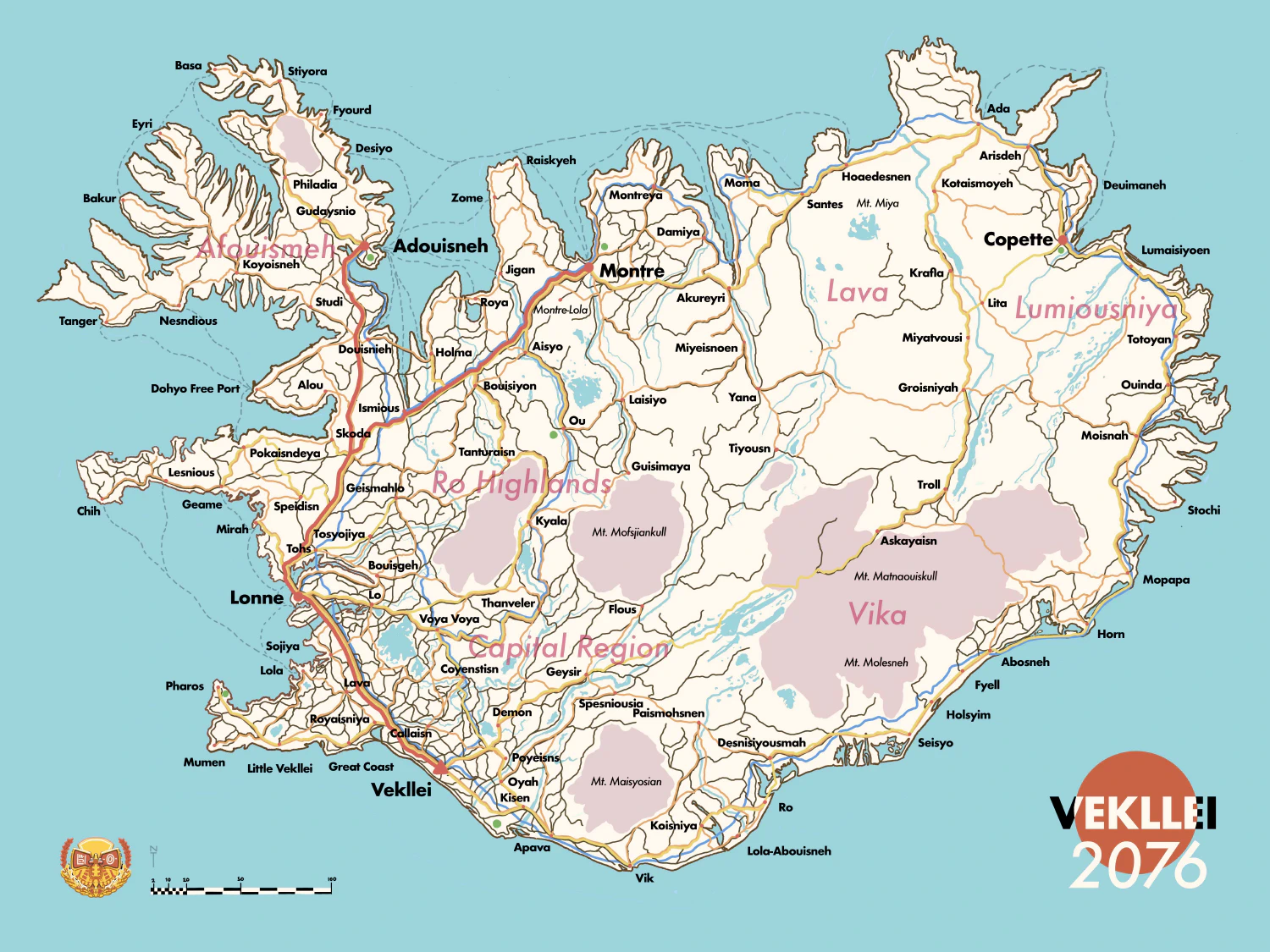

Map Key

Red: Magjet trains, 750km/h

Yellow: Bullet trains, 300-400km/h

Orange: Regional trains, <150km/h

Brown: Local trains, including limited express, <100km/h

Blue: National highway

Dashed: Ferry line

Green: tarmacadamed airport

The largest division of any portion of Vekllei land is the borough; a region of varying size and population with common culture, food dependency and economic interest. Anything larger than that is simply Vekllei — they are “one city”, after all, and consider themselves a city-state.

There have been exactly 100 boroughs since 2015. Each is named after the largest city in its region.

- The smallest borough is Bakur, in Afouismeh, with a population of 7,500 people.

- The largest is Vekllei proper, in the Capital Region, of 2.4 millions.

This transit map illustrates all 100 boroughs, Vekllei’s five tallest mountains, its permafrost glaciers and Tzipora’s home in Montre-Lola. Her five largest boroughs — namely Vekllei, Lonne, Adouisneh, Montre and Copette, are highlighted.

Even in this simple transit map we can see several truths about the country, like its population bias on the West Coast and the emptiness of the Lava volcanic region. You might recognise a few names there, like Lola in the West (Tzipora’s home with Baron) and Yana in Vekllei’s Ro Highlands (Ayn’s birthplace).

Trains are clean, reliable, fast, efficient and safe. They are incorporated under Vekllei Rail, owned by the Transport Group Bureau. Using this map, designed for domestic tourists and foreigners, the adequacy of Vekllei’s rail transport is easy to plan around — you can eat breakfast in a cafe in the seaside town of Mumen, and hike before midday on the glacial slopes of Askayoisn. Since there are no tickets or costs, there are no excuses for not visiting relatives in the country, now that transport is now a trivial inconvenience.

Each borough is represented in Vekllei’s parliament by an elected representative. These representatives wield extraordinarily disproportionate power — the representative for Callaisn, for example, represents hundreds of times more people than the representative for Tanger, but both have the same vote. This is because boroughs are not just representative of their populations, but also their environments, industry and other social organs otherwise unable to vote. It is important to keep in mind that Upen (and consequently, policy) recognises the landscape itself as the sovereign organ of the country, and so in this sense it has its own interests and projections.

In practice, representatives act in an advisory, nonpartisan role in government, voting rarely in an auxiliary role to the professionalised, elected legislature. Vekllei has a strictly constitutional parliament, and the economy largely prohibits interference. In this sense, the parliament is both partially undemocratic in its inefficiency and apolitical in its orientation as a sort of civil service bureau, managing state affairs and reacting to pressures and the long-term aims outlined in the 2015 constitution. In the Vekllei mindset, the “government” is more or less another bureau, no different or particularly more interesting than the Transport Group Bureau. The trains, at least, have a tangible impact on their daily lives.

How appropriate, then, that this transit map produced in the summer months of 2076 combines both monuments of society. It also offers a glimpse of a larger, documented country not necessarily revealed in piecemeal story posts.