NEW Story: Sunday Morning

Face to Face with Immortality

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

Tzipora had never been taller than anyone in Vekllei at a meagre 5’2, but she was taller than Shizuku Kobayashi. Like Tzipora, Shizuku had not physically aged a day since she was a child.

It was summer, and six days after Tzipora had arrived in Japan as a Gregori ambassador from Vekllei. Although she would not be the oldest victim of Gregori-Heitzfeld syndrome until Quentin Cook’s (USA) infamous murder-suicide ten years later, she was one of the so-called “First Thirteen” publicised patients, and so was somewhat known to the international community. By the time of their meeting in 2071, there had been an estimated 250 Gregori baby births, and around 130 living across the world. Kobayashi was the 122nd ageless child, and Japan’s first.

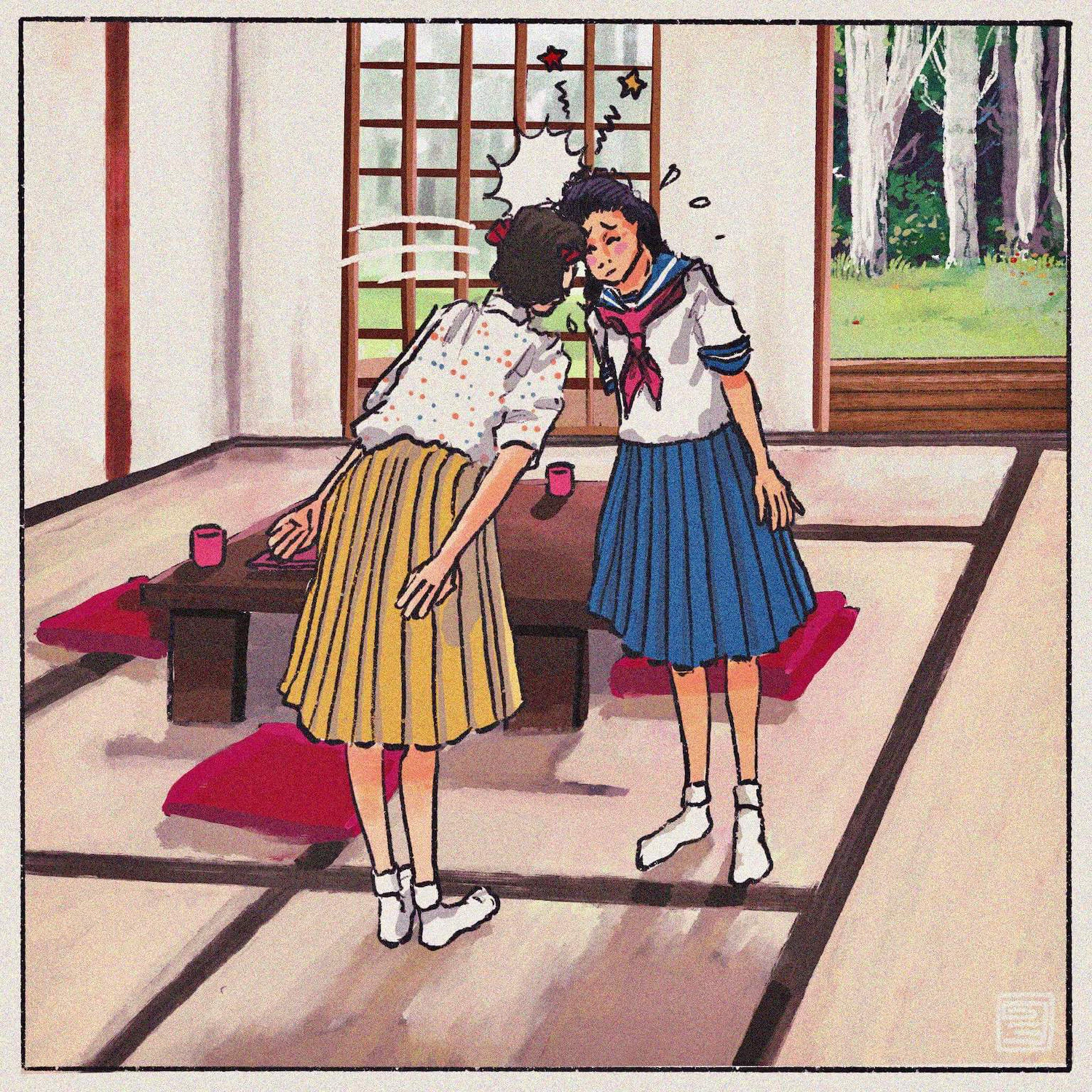

Tzipora met Kobayashi in the Ozake Ryokan outside Kamigōri, Kobayashi’s birthplace and home. It was not far from Aioi. Tzipora was 24 at the time, and Shizuku was 18, and still in school. Poor Zelda was so nervous about meeting another Gregori baby that she became overwhelmed by Japanese manners. So it was that Shizuku’s first introduction to Tzipora was via a clonk on the head.

Shizuku was sweet and even-tempered, and they talked for nearly five hours before she was retrieved by her mother in the late evening. She spoke okay English, because she’d dropped out of school for a year to pursue acting with an American film company based in Yokohama that operated through the NGHQ. Acting was a common profession for Gregori babies — it seemed that the miracle children of the world were quickly relegated to freaks of entertainment. Tzipora did not have the stomach for it, but she knew of several others around the world who made good money playing children in film.

Tzipora excitedly relayed the awkwardness of life in Vekllei as an unageing child, from her problems at university to her dreams of the future. She had no metric for how it might differ in Japanese society, because in many ways she was still fourteen — the problems of a young teen-age girl seemed universal, even then.

“No one takes you seriously at first,” Tzipora said, but she acknowledged that once people got to know her she’d had no problem being treated with respect.

“I suppose,” replied Shizuku.

Tzipora could not help but notice that Shizuku looked different from her Japanese peers. It was only later that she would learn that Shizuku’s father was a GI from Okinawa, shamefully rendering her eternally “hafu” despite the miracle of her existence. She could sympathise, in her own privileged way — Tzipora, too, was a girl of many ethnicities and cultures. But even with her television understanding of the land of the rising sun, Tzipora grasped that things might be more difficult here, where old-world memory collided with new-world growth.

Tzipora quieted her obnoxious enthusiasm and asked Shizuku what pictures she was in. Shizuku said she wasn’t in pictures, just television, and Tzipora wouldn’t have seen them anyway. Tzipora asked what she wanted to do. She said she didn’t know. As for Tzipora?

“I want to work in a library,” Tzipora said. “I love stories, and I like the idea of being in charge of the books.”

“I love stories too,” Shizuku said. “I’d like to write them, really. But we’ll have to see. It’s difficult…”

She trailed off, perhaps lost in her foreign vocabulary. She didn’t have to finish the point. It was difficult: it was difficult to make money, it was difficult to find love, and it was difficult to picture a future where the only constant was yourself. It was no wonder that Gregori children, whose personalities were often developed by the projections of those around them, ended up killing themselves when the uselessness and meaninglessness of their existence revealed itself.

Although Shizuku’s mother received money from the estranged father, and Shizuku herself had made good money through acting, a fugue settled on Tzipora in the days after their meeting. Previously she had not considered herself a “Gregori baby;” she had considered herself merely “Tzipora”. In Vekllei, that was an identity she could afford. But despite Shizuku’s outward satisfaction with her present state of affairs, Tzipora couldn’t help but feel ill thinking about the anxious, isolating existence that almost certainly awaited any girl whose childhood stretched into the decades. All at once it seemed very unfair in its quiet cruelty — the hafu girl who would never grow up to be a beautiful actress.

Although she’d kept in contact with Shizuku Kobayashi, Tzipora would not visit another Gregori baby for many decades.