NEW Story: Sunday Morning

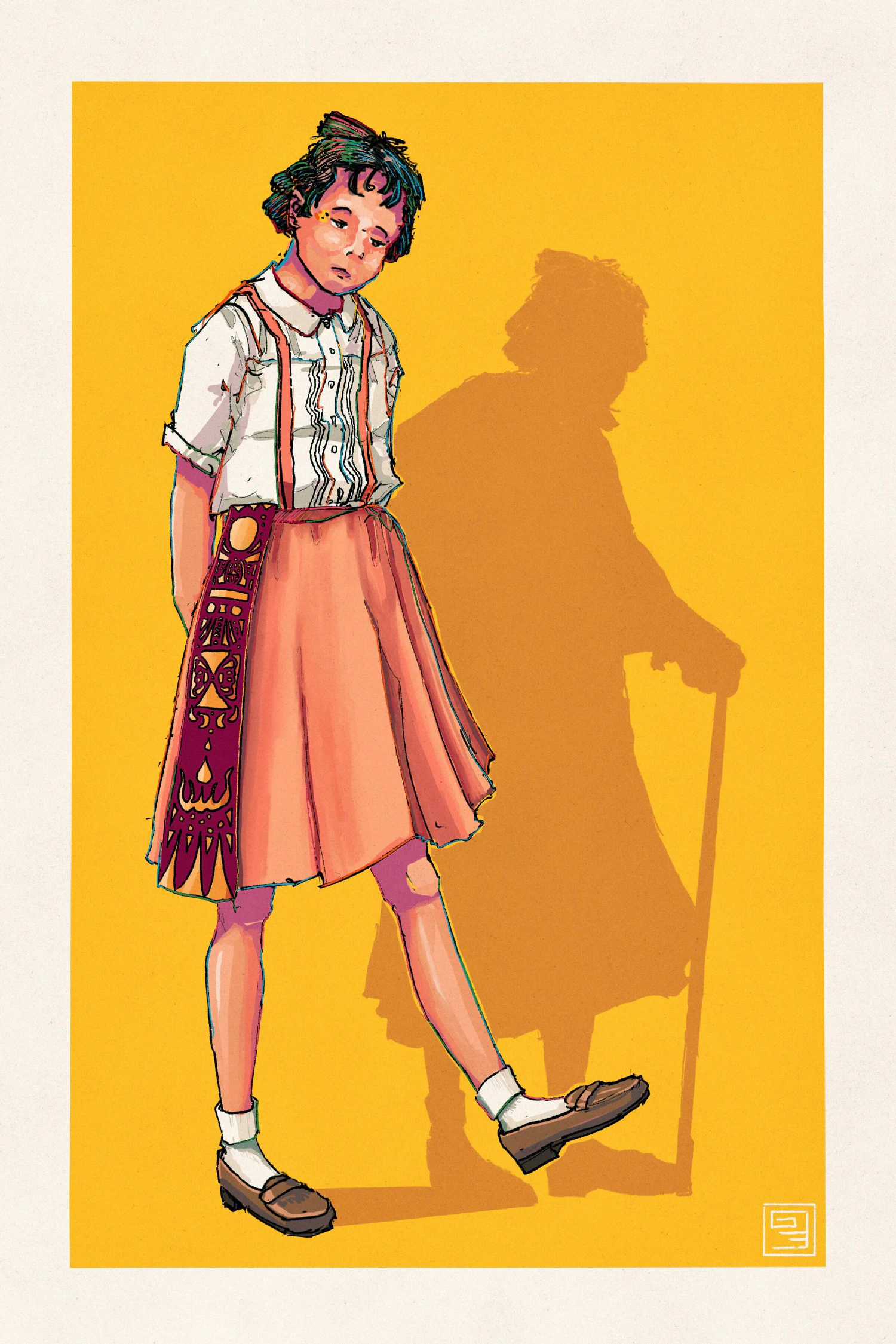

The Thousand-Year-Old Girl

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

✿ This article was featured in Issue #4 of the Atlantic Bulletin

The concept of living forever jumps out at people uncomfortable with their own existence. There is a contemplative instinct among educated people that — if they could simply will themselves into a state of self-actualisation — death would only be an obstacle to greatness.

As Tzipora found out quickly, the opposite was true — death and temporality were wells of meaning against which all great people, beauty, and human constructions were cast.

Tzipora Desmoisnes is what is known as a Gregori Baby, a catch-all term for a unique genetic condition that has seemingly produced a variety of miracle children appropriate for the frothing futurism of the atomic age — boys and girls who, suspended in the purity and good-naturedness of childhood — live forever.

There is no single “Gregori Baby” — each is unique, and Tzipora is the 13th to have been recognised overall. The phrase is a shortening of Gregori-Heitzfeld syndrome, a stand-in for medical information that isn’t there. The first, Gregori Hordiyenko, was born in 2024. He was healthy, and died of unrelated causes in his 20s. Tzipora, at 13th, continues to live to this day and is the oldest person on Earth.

There is a disturbing trend among the Gregori children, first heralded as miracles and symptoms of the space age, to deteriorate medically as more are born. The culprit is the malfunctioning of telomeres in their DNA — the source of their longevity — which regularly produce devastating chromosomal disorders, including Trisomy 13 & 18, killing most “ageless children” before their third birthday. Those that survive are often victims of a severe anaphylaxis caused by a hyperactive immune system — rendering many of them permanently sickly. Others find themselves unageing, but continue to grow — reaching as tall as 2.5m before their bodies give out from exhaustion and osteoporosis.

So what is Gregori syndrome? What does your average (healthy) Gregori baby look like? Their genetic miracle is linked to the structures of the body that activate at puberty, and so girls vary between 11-16 years of age at onset depending on many factors that affect their development. Boys tend to be a little younger, from 8-14. Between the two, girls tend to be more stable, and all but two of the supercentenarian Gregori children are female.

Among girls, they are prepubescent and generally stop ageing on the eve of menarche, or their first period. In Tzipora’s case, her body is estimated to be 13 years and 11 months old. Unlike many Gregori children, Tzipora lives in a wealthy country and has volunteered for extensive research into her genetic makeup, meaning that much of early medical documentation around Gregori-Heitzfeld syndrome was received directly from her case.

Most obvious is that, at a foundational level, her cells are similar in function to unipotent stem cells, and have been since hormones at the end of thelarche suspended her ageing. This change has occurred somewhere in her DNA — exactly where is unknown — but the end result is that, unlike regular progenitor cells that make up most adult bodies, the building blocks of her body are capable of cell-renewal. Her telomeres, the endcaps of chromosomal DNA in mammals, are undamaged. And so there is an amazing shift in her basic human structure — in which human cell lineage, which usually ends in a mature cell incapable of division, is caught and rearranged. With this considered, it is no wonder that Gregori children suffer from such catastrophic chromosomal instability, and why healthy ageless babies are a rarity. Her body is not exactly a “body of stem cells,” but for their function in a healthy Gregori child, they might as well be.

So it is that nothing about Tzipora is changing. She suffers from pains in her legs often — called growing pains, although they are not from growing — and her cells continue to replenish, albeit at a rate 1.25 times that of normal people. She is, in essence, “growing” as any other premenarchal girl would, but she is not getting bigger or becoming older.

Tzipora is blessed with an adult life in Vekllei, where the “Child” does not exist as it does in the West, and her individual freedoms are far-ranging. She may smoke, and drink, and has held many different jobs in her life. She holds two doctorates in English and Vekllei Literature. She is obviously sterile — even if she were to somehow “age out” of prepubescence into pubescence and receive the required hormones, she simply lacks the genetic code to reproduce — but raises many children through her active participation in village life and her roles as Montre-Lola’s municipal and school librarian.

In other countries, with coded roles for children, their problems are much greater. Unable to form adult relationships and often incapable of finding work, many work in entertainment or fall into poverty as they outlive their friends and parents. Socially ostracised and forever young, many are victims of superstition and fear. As the pattern of Gregori children indicates an increase in mortality, even as more are born, their appearance is both a miracle and a tragedy — ageing not through mitosis but through weathering the societies in which they live.