NEW Story: Sunday Morning

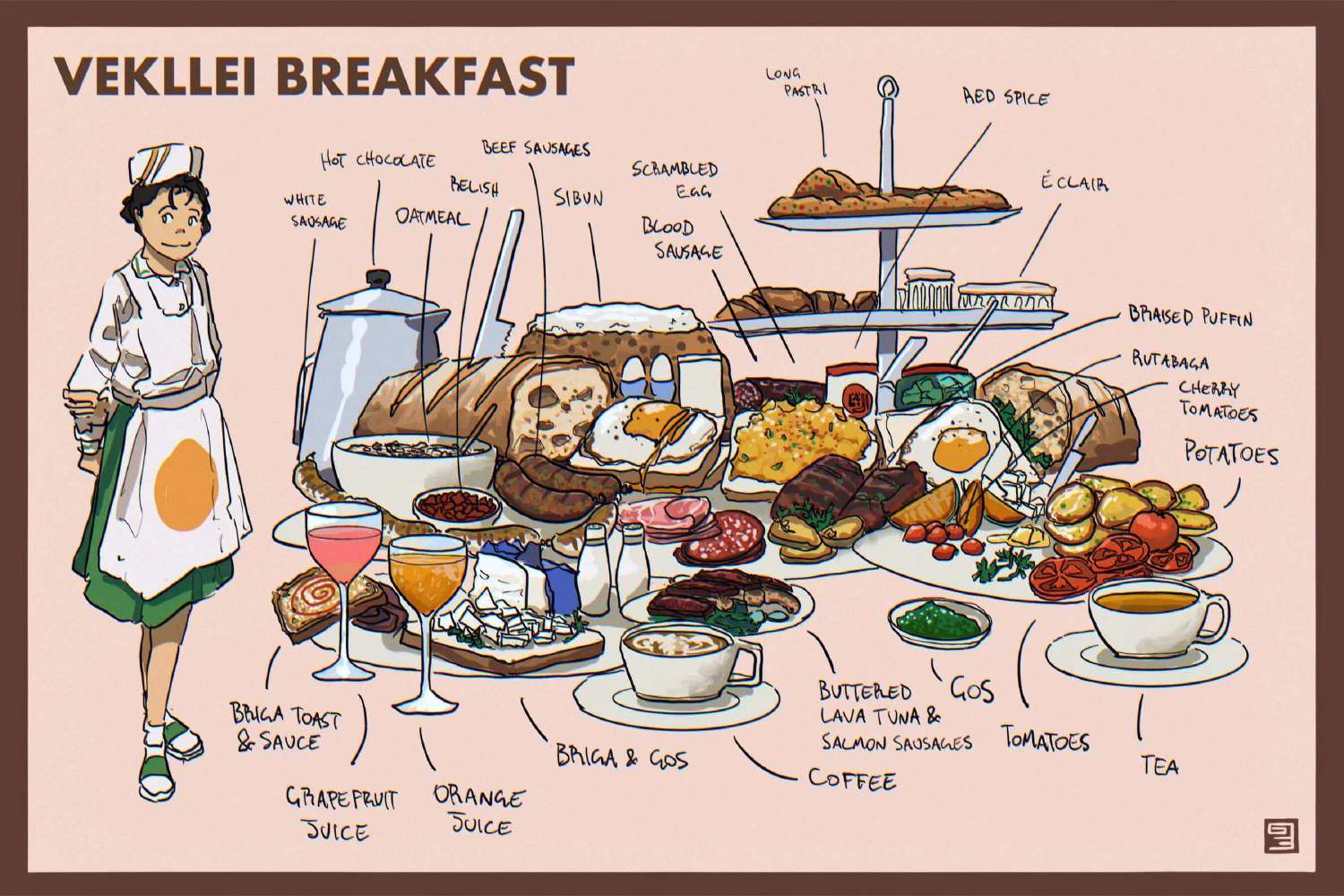

A Vekllei Breakfast

Postwar Vekllei has a problem. In the old days, many hundreds of years ago, Vekllei’s long, dark winters forced subsistence farmers to preserve their dishes for six or seven months of the year. This changed under the Junta, which opened trade with the Scandinavian powers, and Vekllei soon saw its growing population dependent on fresh imports of oats and grain from Europe. These Atlantic people, whose diets were previously gamey and nomadic, were now a rough storm away from famine.

Today, the diets are the same but the pressures on food production are even more intense. This island has nearly 22 million people on it. The postwar Vekllei Government is terrified of the vulnerability of its indigenous, isolated ecosystems, and heavily restricts raw food imports. Meanwhile, Vekllei cuisine values freshness, localism and sustainability. These are facts that cannot coexist in a place that cannot reliably grow food outside for half the year.

The simple answer, then, is that Vekllei cuts corners on its food production. It does not attempt to reliably produce meat, which effectively banishes traditional cuisine to rural areas and those willing to hunt puffins themselves. For what animals are slaughtered, all parts of their body are used, and quite often all you’ll find at a butcher is sweetbreads and black pudding. Quality meat is synthetic, grown as isolated cells in massive liquid solutions. Even blood and organs are synthesised in industrial quantities for human consumption. Vegetables, which only entered the mainstream diet of Vekllei in the 20th Century, are grown in huge quantities under sun lamps, powered by limitless fission. The factory process of synthesising foods is called sincrestiprosmaious (lit. Grown/Made Produce, or similar).

With these unusual facts in mind, let’s take a look at a breakfast feast prepared by Commis Chef Tzipora, which features a selection of indigenous Vekllei breakfast foods.

The basic composition of a Vekllei breakfast is its proteins (egg, meats, and cheese), drinks (coffee, citrus juice, or light breakfast tea), fried or raw vegetables (potato and rutabaga) and sweet items (usually a bun, pastry, or breakfast roll and honey).

The humble egg is a staple rarely in short supply in Vekllei, and one or two are scrambled or fried most mornings, often assembled on rye with briga (a soft Vekllei cheese with a taste similar to feta) and gos (bitter Vekllei moss). Scrambled eggs are especially popular due to their availability, a result of their ease of synthesis, and flavoured with red spice (factory chilli) or herbs.

Genuine meat is scarce in Vekllei and eaten only occasionally, most commonly in rural areas close to livestock. Most genuine breakfast meats consist of cold, sliced ham or sausages, which are packed with breadcrumbs due to meat scarcity. Vekllei has a type of blood sausage made of genuine pork blood or synthetic substitutes grown in stem cell hematopoietic vats, which are packed with oatmeal, groats and mint, making a black pudding called rue bouismesn (lit. Blood Sausage). Lamb sausages, called blanc oa bouismesn (lit. White Sausage) are also common.

Vekllei people drink a lot of tea and coffee — about 7 pounds a year of each. They eat a lot of bread and pastry — about 200 pounds a year. They like their butter and lamb, but don’t go in much for pork. Game, like puffins, are eaten regularly, though less than seafood or lamb. All of these items are eaten with breakfast in various ways, most famously agne loh lebeau (lit. Lamb Butter) which is a delicious buttery meat spread for toast, or lava oa agnetunfisk (lit. Buttered Lava Tuna), which is cooked until it falls apart and assembled with potatoes and eggs.

Vekllei people like rich, sweet foods, and we can see that here at breakfast. Coffee is sweetened with condensed milk or raw sugar and stirred thoroughly with milk. Tea is much the same. We have here a long pastri, a “long pastry” filled with fruit, which is eaten with (and often dipped in) your hot drink. A large spiced bun with coconut icing, called a sibun (lit. Pale Bun) is a native favourite.

Vekllei people love food. In a way, it has satisfied the vacuum of moneyless society. It is bargained for help, traded for goods, and gifted for favour. It is also one of the largest compromises of Vekllei’s way of doing things. Upen has a very clear materials hierarchy — things made by you, from things around you, which you understand and respect are best. Below that, there are high quality local things made by others. At the very bottom are synthetic, man-made, factory-produced materials churned out to meet demand. Food in Vekllei undeniably exists in this last category for the vast majority of city-dwelling people.

You can reclaim the spiritual purity of foods somewhat by simply loving the ingredients you obtain — the black pudding might be grown in vats, but why not transform it by crumbling it over a salad with a nice vinaigrette you’ve made yourself? To alleviate some of this metaphysical tension, most Vekllei neighbourhoods are filled with greenhouses and local shared gardens, which ensures most meals have some produce in which you have participated. That’s very important. Some people think that, because Vekllei has abolished money, it has abolished the fetishism of products. The opposite is true — Vekllei life is about the love and respect of materials, a feature built into the animism of Upen. You cannot buy the best food in Vekllei — you have to find it, in a trial of ownership.

Sitting down and enjoying food is a cornerstone of life in Vekllei. You cannot participate in society without it. For immigrants, the privacy of a quiet breakfast is good practice for the palettes and conventions of eating in Vekllei — so load up your plates.