NEW Story: Cocktail

Life and Death in Vekllei Apartment Ideology, or “Newda”

This article is not part of Vekllei canon. It may be old, obsolete or just a bit of fun.

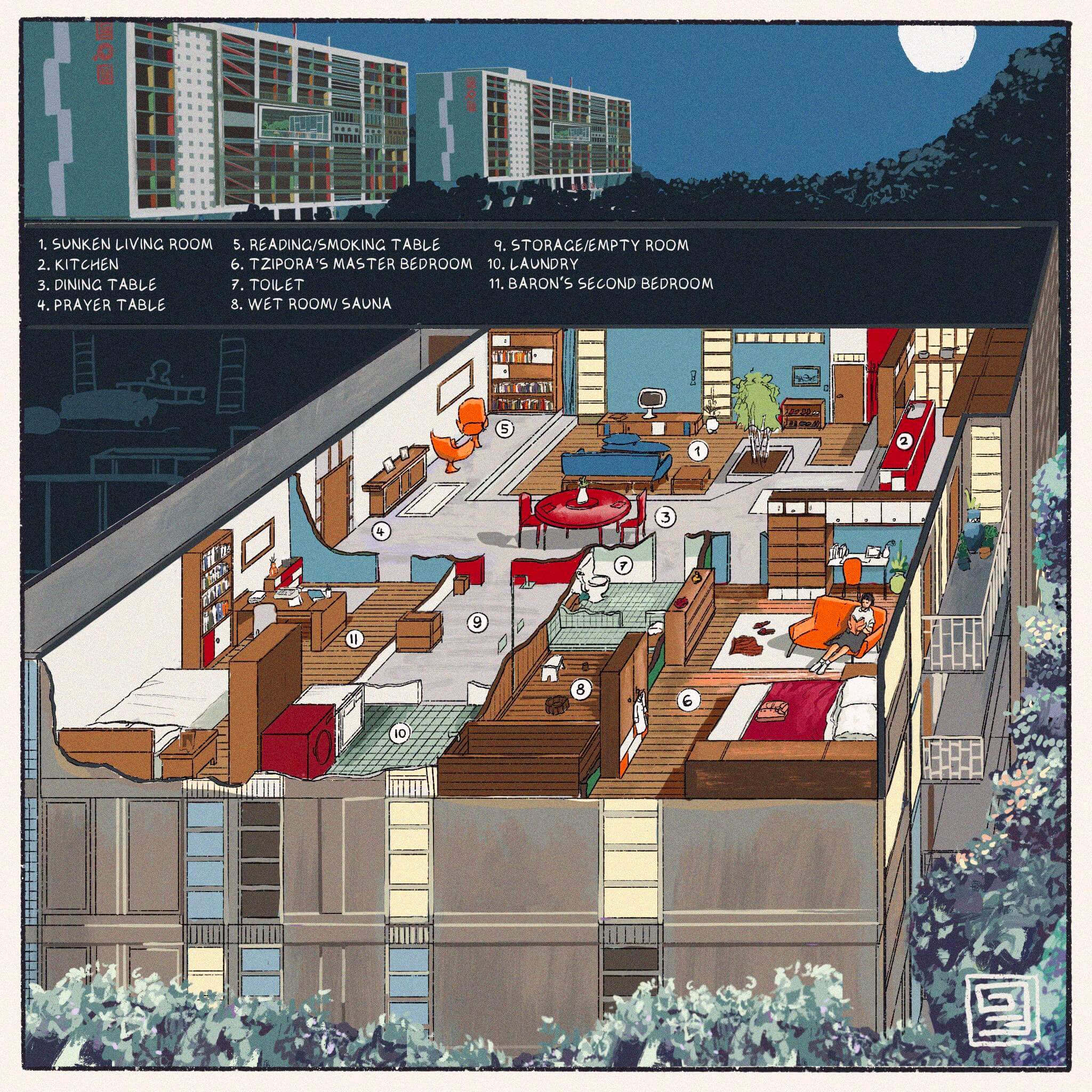

To substitute for my shocking (and deeply shameful) absence over the last two weeks, please accept a longer-form post concerning domestic Apartment Ideology in Vekllei, which they call Newda and is known internationally as The Vekllei Newda School. Pictured is the apartment of our very own Zelda. While the building itself deserves a feature, for now we’ll discuss Newda as a theory and her life in this building. If you get bogged down and pissed off at the jargon, skip to the “practice” section. I’m not sure how I feel about this post, I might have indulged too much, but either way, I’m BACK. – Hobart

Argument #

“A man of the eighteenth century, plunged suddenly into our civilisation, might well have the impression of something akin to a nightmare.”

— Frederick Etchells, Towards a New Architecture.

Some critics of architecture (and adjacent slugs) deride Newda as decadent. It is as incestuous and plastic as most other modernist constructions, they say. It mistakes austerity for utility, and le blanc for cleanliness. This is not an unreasonable criticism, especially since foundational Vekllei cultural principles of natural immersion and human decay seem irreconcilable with the white, shining concrete of her modern cityscape. How does a style like Newda claim to be anything other than a reckless adoption of continental urbanism for its own sake; a symptom of the social decay we call postwar austerity?

For these people, Newda represents a grotesque squandering of a rare, virgin landscape which had been wiped clean in the atomic war. It is impossible to imagine any other means by which the opportunity to rebuild today’s modern cities might arise. She could have been Paris, critics say — entirely unaware that they are discussing a city more beautiful than Paris. “Oh, to see Rome reduced to urbanist tower-blocks”; “a garden city of concrete and asbestos”; “a cauldron of plastic and rebar”; and so on go the tears. “Never had tacky decadence looked so plain.”

“There exists a new spirit,” Le Corbusier wrote in Towards a New Architecture. “Our own epoch is determining, day by day, its own style. Our eyes, unhappily, are unable yet to discern it.”

What a tantalising phrase that was, when it finally reached Vekllei’s shores from his native France. Not just for its celebration of a young era, which appeals to Vekllei’s fluid and agnostic antihistoricism, but for its appeal to “spirit”, which gestures towards the intimate and gentle Vekllei nature. Hence the critics’ fundamental mischaracterisation of Vekllei’s great modernist project — namely that the country understands nature as an organ alienated from their “civilisation,” or that they recognise their æsthetics as a progression of history. Neither is true, as is plain to anyone who has been to any part of Vekllei. Landscape is suppressed in Vekllei, even in an industrial age, and so there is no schism between the human and the natural worlds despite the fact that they live in tower-blocks and wear clothes of rayon and gingham. And “History” in Vekllei is gutted as easily as they might a tuna for which their cuisine is known; their collective story as a state is one of movements and gestures, laterally and lineally at times, and “backwards” at others (although to apply such a word to Vekllei is to criminally misunderstand her project).

It is the application of sickly sentimentalist instincts to Vekllei that betray the reactionary criticism of Newda as a “superficial, austere school of architecture” for what it is; a deeply historicist suspicion ingrained in the same modernist instincts it claims to critique; at once fucking and wagging a finger at the pig. It is also a brash rejection of Vekllei sociology as a foundation of petticoat ideology, and mistakes Vekllei’s “material culture” (her buildings, her clothes, her toys) as something somehow disconnected from so-called “petticoat intuition”, which is just a phrase for the social unconscious that forms consensus in the country on everything from television soaps to her beloved tower-blocks. This is aesthetics in action, what Hegel praised in The Philosophy of Right as “philosophising, which could well have continued to spin itself into its own web of scholastic wisdom, [coming] into closer contact with actuality.” Newda is real, and it is alive in the instincts of the ordinary Vekllei person.

Paris can burn. Newda will survive a thousand atomic strikes, through that cockroach known as ideology.

Do not let Vekllei architecture, which might be assaulted by promiscuous subjectivity or the bores of American objectivity, be discussed in anything but a sociological arena. When talking about Vekllei things, it is a mistake to rely on uniquely Western (or otherwise) constructs. As Adorno noted in Aesthetics, taste is preprogrammed — the “sublime,” so it is invoked, is spiritual phenomenology, dependent on so-called objectivity only insofar as objectivity relates to your postcode and personal wealth. Tell a man he is listening to a Stradivarius and replace it with any other violin, and watch the sublime grow mold.

Theory #

Decoration has nothing to do with sophistication, nor spirituality. Vekllei is characterised by honesty as a premise in itself — not in how they talk or how they do business, but in the frankness and clarity of Vekllei culture in ideology and its cities. “Honesty” is to make plain the exact functioning and beneficiaries of the economy; the production and movement of commercial goods; the labour and value of “commodities”; and the material and operation of machines and structures.

So too should it inform the foundations of life. Housing is one of the greatest urgencies in the mind — and so architecture should respond to urgency with the solidity and reliability required of it. That essence, or “form,” is the premise of a structure, and it requires the reestablishment of architecture not as “style” but as an ideology built upon a place of living defined by form, purpose, and purity. Newda is characterised by large light wells, common areas, the integration of civic essentials (like food-production, hydroponics, gardens, shallow pools for washing and bathing), and expression through shape. In form, Newda is defined by strong vertical geometry, the baring of utility including pipes and water tanks, and strong colour. Newda structures are constructed in béton brut, even in smaller villages, abiding by the principles of dumousiantopet, or ‘beautiful and seperate’. A Newda structure is large enough to house a community but appears gentle and lightweight, since it perches majestically on large columns.

There are many types of Newda buildings designed in many different languages and principles of architecture, but I’m approaching the character limit here so we’ll pursue them another time.

Practice #

Let’s take a tour with Zelda on her journey inside her building.

Facing the street is a conservatory atrium of ten stories, which is filled with trees. It opens out into the air at its base, since the entire structure is raised on elegant columns that encourage the ground floor as a place of public living. The path to the central elevator towers are lined on each side by a wading pool with a depth of one meter — the pool tiles are bright-coloured and contrast each other. They make a good place to cool your feet in summer. Since the load of the structure is vested in columns in the interior, glass encircles the atrium façade like a ribbon, serving as a natural lightwell and growing space for produce-bearing plants which supplement the Vekllei diet.

Zelda calls an elevator at the free-standing tower, since she lives on the eighth floor. The elevator is glass-lined and she soars up through the canopy of the indoor forest as it moves. The apartments of the eighth floor open into lome a’ pasænet or an ‘internal street’. These are found in most Vekllei apartment buildings. The street is a long balcony, decadently wide, that runs the length of the interior and connects the five apartments of that floor. Large glass windows in the apartments look out into the internal street, or are hidden with curtains in times of privacy. The street is a popular place to read or meet friends and neighbours, since the yawning interior multiplies the sense of space tenfold, and it received direct sunlight throughout most of the day. At sunset, the glass façade of the public interior casts a warm, fantastical light on the ten streets of the ten-story building, transforming the space into a prismatic cathedral of light.

Stepping in to the footwell of the apartment, Zelda removes her shoes. There’s some rumour about the custom dating back to the Viking days as a sign of peaceful intention, but today it’s for cleanliness. The living room is sunken, and is lighted by the windows looking out into the interior street, which receive sun about the time she comes home. The kitchen overlooks the living space and indoor fig, and includes a large partition/cupboard that can roll on rails across the width of the apartment. There are many small examples of similar modularity throughout the apartment, balanced carefully with Newda’s affection for permanence. Pipes run beneath the concrete for underfloor heating, providing toasty floors in Vekllei’s dark, brutal winters. The apartment is divided between a semi-public half, which includes the living, dining and cooking areas, and a ‘private half’ which contains the two bedrooms, bathroom and laundry.

Zelda took the larger bedroom despite her initial protestations — Baron insisted, and so that’s where she spends all her time when he’s not home. It’s by far the biggest space she’s ever had to herself. In fact, thinking back, this is the first room she hasn’t had to share since she was ten. In other buildings it would be large enough to house a cramped studio apartment.

Next door is the bathroom. There, you’ll find a French bidet, which is separated by a wall from what looks like, at first glance, a modest oriental wet room and bath. The precise opposite is true. It is a Vekllei (that is to say, Scandinavian) wet room. Instead of cleaning your body with a shower and bucket and then soaking in a hot bath, a Vekllei person scalds their skin until it glows and then plunges into a tub of cold water. The contrast of temperature encourages vasodilation and then constriction of the circulatory system, which, in addition to the hydrostatic pressure supplied by the bath, invigorates the skin and can help with muscle fatigue. Some experts believe it may aid the immune system. Vekllei bathers generally do not spend luxurious amounts of time in the bath or shower — cleaning is a utilitarian process, which, while shocking and stressful in its temperature contrast, leaves the bather refreshed and with sensitive skin that lends to a feeling of sterility. Public baths work much the same way, through the scalding and cooling principle.

An empty storage room, indicative of Baron and Tzipora’s spartan minimalism, conceals a small personal laundry. A private laundry is considered luxurious in Vekllei, especially in urban areas where such things are easily communalised, but these apartment towers are new and these are among its benefits. Finally, there is Baron’s bedroom and study. Like his daughter, he is a creature of routine, perfectly acclimatised to a home of any size. There is enough space here for a full-size electrotype and the books he needs to work from home on the occasions that permit it. Just beyond his door, in the living area, is a prayer table for their respective friends and family who have passed on.