NEW Story: Cocktail

The Atlantic Bulletin

From the Editor #

Welcome to the inaugural issue of The Atlantic, a monthly bulletin for enthusiasts and fans of the Petticoat Project, Vekllei, Tzipora and its constellation of interests and affairs. For the benefit of compatibility, The Atlantic is published in websafe typography to keep this bulletin looking great on any screen.

If you would like to contribute to The Atlantic with writing, art or reviews relevant to the spirit of petticoat ideology, please contact Hobart at [email protected] before the 31st of June.

Thank you for supporting Vekllei, and I hope you find value in this bulletin.

Enjoy — 楽しんで

I. News & Announcements #

- To celebrate reaching $50 a month on Patreon, Hobart plans to illustrate, print and ship six full-colour postcards and ship them to Patrons whose total lifetime pledge comes to $20 or more. Contact [email protected] for inquiries and eligibility (or through any other available contact). Currently 2 out of 4 are completed, with several others in various states of completion. They will be done by the end of June and printed in July.

- The Studio MillMint site is undergoing major renovations thanks to the contributions of Ben_R_R#2574, a longtime patron and friend of the project. Changes to the site will be announced as they come in this bulletin, the #lounge and Patreon.

- The Atlantic bulletin is launched. There will be twelve issues a year. They will feature content of interest to fans of the Petticoat Project.

- Hobart has his final assessment task due on the 12th of June. Post schedule may suffer leading up to this period.

- The Patreon has hit $80 a month. That’s an incredibly amount of interest and I’d like to thank all patrons for their financial support — it helps keep the lights on and gives me hope that I can work full-time on the project some day.

II. Tzipora-watch #

May 5th is Tzipora’s birthday. She spends her birthday with Baron and Ayn; her friends are relegated to the day after.

III. Vekllei Fact of the Month #

You might be aware of venrouive and senrouive property, which mark ‘essential’ and ‘personal’ business respectively, but there is also a rarely-used third classification called uousinasenrouive. This means, roughly, “property-obligation”. These places require a physical obligation from their owners, usually a debt owed to the history of the place. For example, an apartment above a bakery would usually fall under such a category, since living there would require operation and maintenance of the business also. Uousinasenrouive are very common in Vekllei, and many older residences involve these work obligations.

IV. The Bulletin #

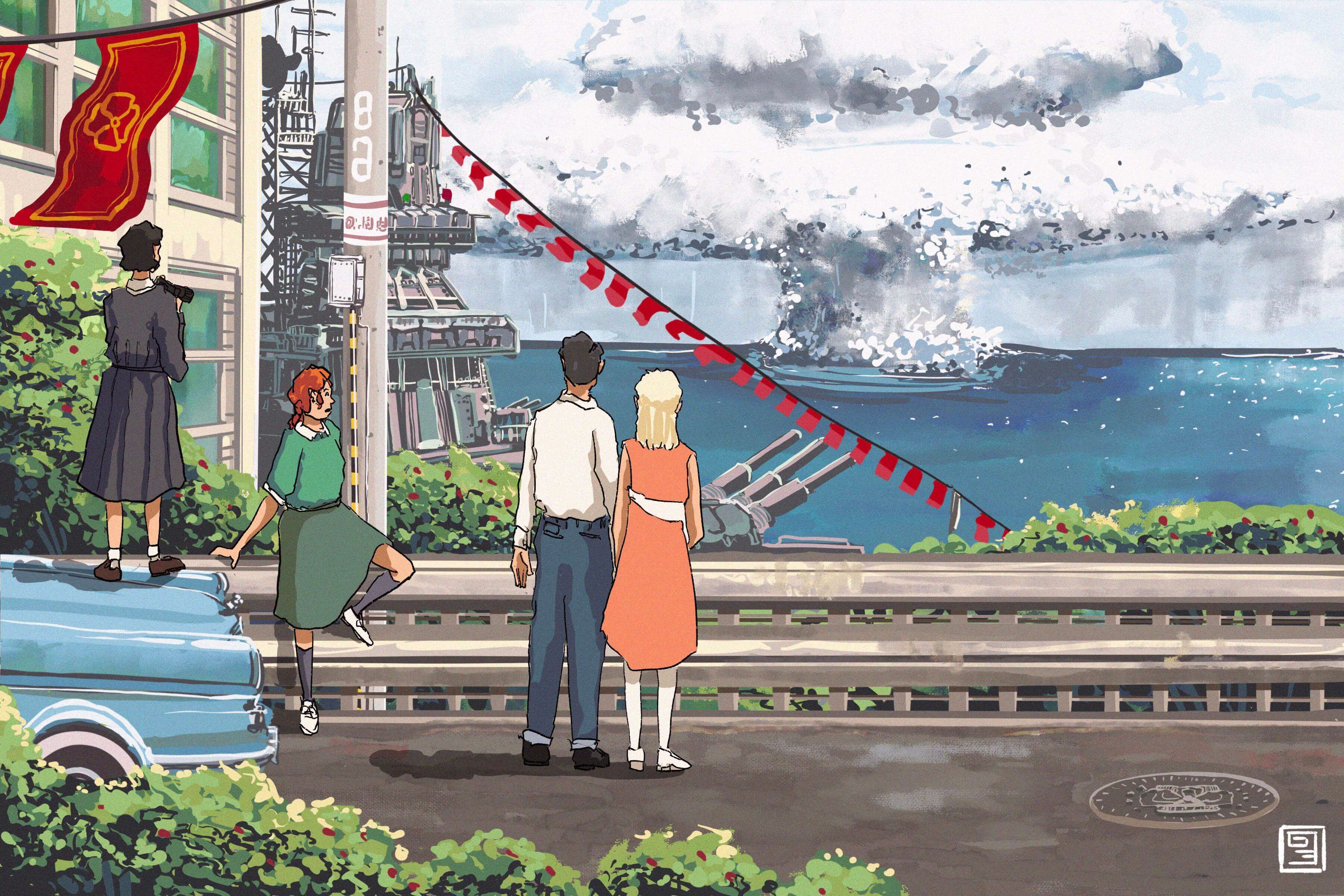

Fission Cloud at Vekllei’s 50th Anniversary #

📖 Published 31st May 2020 | Read here.

In an unprecedented event, during Vekllei’s 50th Sea Festival since Independence in 2065, an 8 kiloton fission bomb was sunk to a depth of 150 meters and detonated at midday. It was an incredible sight on a day so clear you could see the gentle curve of the earth where it met the horizon. A flash of light and a spray dome surged outwards into the quiet Atlantic, which was broken apart by plumes that formed a column of water that climbed high into the sky. The lateral plumes, the “mushroom”, reached far across the horizon, forming thick clouds that would begin to rain into the sea. From the coast, fifteen kilometres away, a warm light bathed observers and was followed a moment later by a bang that deeply shook you and those around you. In this instance it seemed that the whole universe was their domain.

The plume would rise nearly 1,500 metres into the sky before falling away. It stayed that way for a while. Almost nobody moved for a long time after — people stood on cars and tables. You could only recognise the scale and the feeling of the fission bomb by seeing it in person. It seemed incomprehensible, in the face of such a device, that wars could still be fought at all. What use is a battleship in the face of a cloud like that?

Tzipora and Elise, covering the detonation for Lola 7th School’s student newspaper, found themselves not quite sure what to say. Elise wrote, captioning Tziproa’s photograph, “The Independence bomb filled our sky with our sea for a half-hour on Sunday, and with it rose the thoughts of every person in attendance, who considered the awesome power now shouldered by each of us.”

There was indeed some sense that they had contributed to the bomb, and that they had more at their disposal. Few would fly the planes to deliver them, and fewer still had the brains to develop them, but participating in a nuclear century contributed to, in some effect, a nuclear horizon.

Hot Rain in the Arctic Circle #

📖 Published 27th May 2020 | Read here.

Tzipora had been ejected from the operations room once the guys arrived. She knew what was going down, anyway. No specifics. But you didn’t bring in uniformed soldiers for regular business. National Intelligence liked to work with their own people.

Five days prior, Baron hailed an EB/NI company car and it pulled up beside him. The electric passenger window slid down. Baron nodded at the passenger.

“Everything’s in here. There’s more if you need it. I’d appreciate a call, I’m in my office all next week, okay?” He passed over a white postage envelope. “Take care.” The British man opened the letter and read it twice as the car approached the Vekllei World Jetport.

JULES WYNN IS YOUR 3RD MAN. “JEREMY” APPEARS IN ARCHIVES 2046 — ALMOST CERTAINLY WYNN. NEARLY 20 YEARS. NOTES TO USSR THRU CYPHER CLERK (UNKNOWN). RECALLED TO MOSCOW — GREAT SUSPICION OF HIM FROM CONTROLLER DOWSETT-CLARK (OXFORD). THIS IS GOOD INFO FROM PARIS ASSET. WYNN WILL DIE IN RUSSIA. GET HIM AND ANOTHER RING SURFACES. CIA KNOWS WHERE BUT NOT WHO. DO US BOTH A FAVOUR.

Tzipora went for a walk to clear her head. She had a lot going on in her life — though she was sure it seemed small compared to whatever was going on in the operations room. It began to rain an hour into the walk. She’d left her umbrella with the rest of her things in Baron’s office. That was okay. She didn’t mind the shower, anyway — it was mid-summer, and the rain was warm. What a novelty that was, at 60 degrees north. This was weather from the sunny Azores, pulled north by the wind currents over the Atlantic. Within minutes her skirt was heavy and her camisole was showing at the shoulders. She blinked heavy streams of water out of her eyes. She passed the soldiers on their way out as she returned to AB/NI reception. A friendly receptionist had cloaked her in a towel by the time Baron had found her.

“Did you have a good meeting?” She asked. “Sure,” and characteristically, he considered that a satisfactory answer. He pulled the towel off her head. “You’re completely soaked.” “It doesn’t matter. Are you with those guys? About that other guy?” “Watch it,” he said. “Keep that talk past security. But I’m going to fly out tomorrow. I’ll be back in the evening.” “No cooking for me, then. Where are you going? Or can’t you say?” “England.” “Oh,” Tzipora said, forming a gun with her fingers. “Like James Bond.”

Her life was a nexus of various global ambitions, it seemed — imagined only through the dreamy lens of a teen-ager too small for the world’s problems.

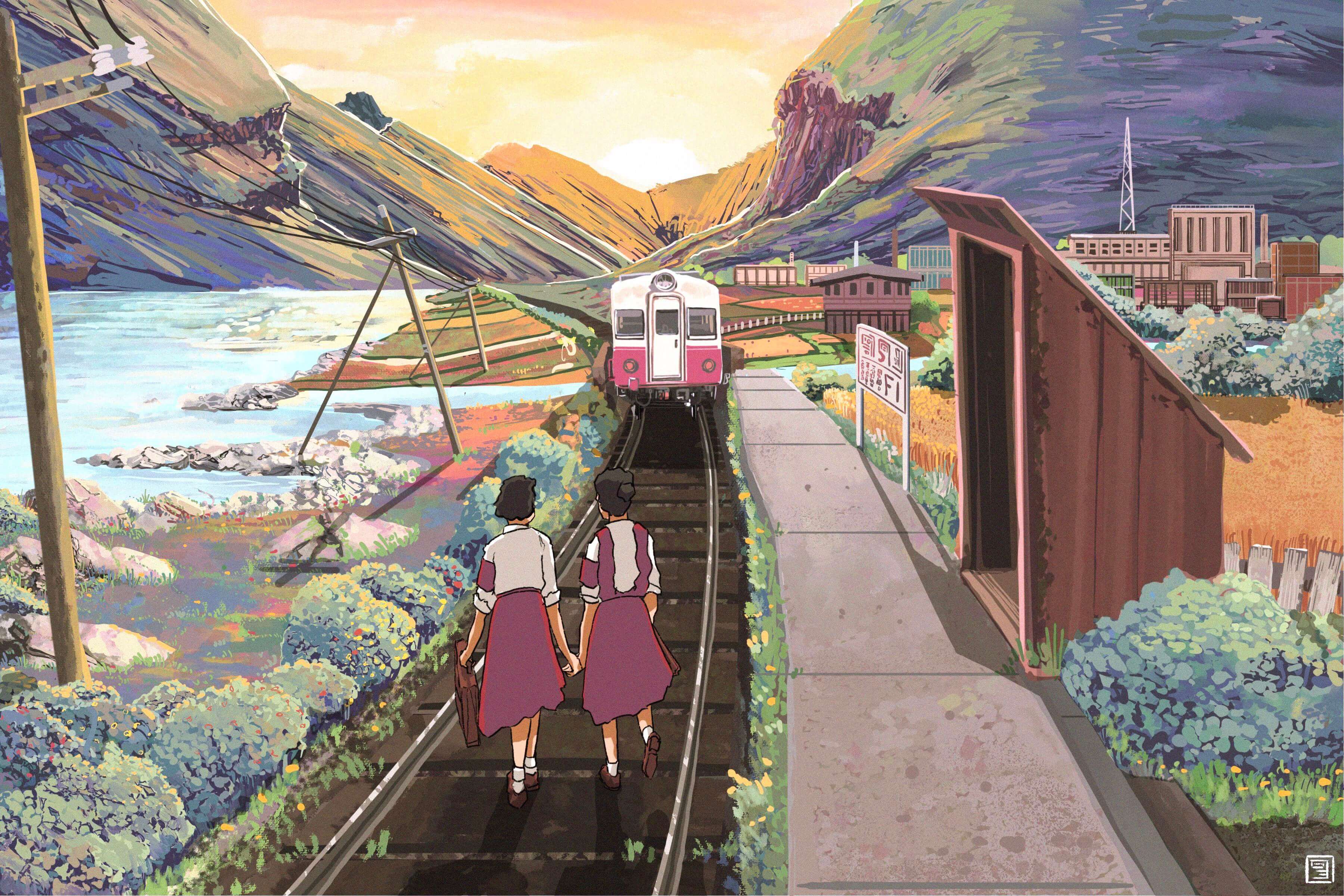

The Last Train Out of Ada #

📖 Published 20th May 2020 | Read here.

They both watched as train 416 pulled away from the platform. And that was that — there would be no school in the morning. That was how it worked in rural Vekllei, a million miles from the automatic trains on endless timetables. Out here, you paced life around the station.

There was not much to say about this, between the two of them. Tzipora looked at Cobian and pulled a froggy smile that tried to express that it was nobody’s fault. Sure — it was Tzipora who had misplaced her purse, and it was also true that it was Tzipora who’d stopped by the orchard to steal a peach, but as to how they’d missed the train? It was simply impossible to say.

“You’re a complete idiot,” Cobian said matter-of-factly, and Tzipora wilted. They watched 416 trundle into the sunset. A picturesque vision of rural utopia — if only they were a part of it.

Winter Uniforms in Vekllei #

📖 Published 16th May 2020 | Read here.

When I paint Vekllei, I usually depict the warmer months. Hems are shorter, days are longer, and the destabilisation of the world’s climate has only benefited these arctic people. At the gift end of the Vekllei low pressure system, Scandinavian misery has become Mediterranean pleasure, with warm summers and a mild Autumn and Spring.

Still, by late October, the the earth is hard with cold and the days are short. The world may be warmer, but Vekllei’s polar latitude is unchanged, and in the depths of winter the sun only rises for an hour a day. These are Vekllei’s “moon months”, and they announce some of the most important spiritual festivals in Upen.

Although school hours are reduced in winter, life carries on and Vekllei fashion becomes traditionally utilitarian. Tzipora has poor circulation and cold hands even in the warm months, and by November she’s traded the skirt and gi for traditional rouisha trousers and a cloak. Rouisha, like a lot of traditional clothing, have origins in agriculture and are characterised by a loose, baggy fit and insulated lining. Cobian is wearing a heavy wool sack-type dress, which is worn like an apron over other clothing. Winter brings forth “petticoat society” literally. Note the leather plate on her shoulder, to which her christmas aiguillette is attached.

In this sense, Winter’s revival of traditional clothing and customs further evidences its practice as the most traditional season of the year. Although the warm calendar flourishes with the futurist sympathies of a modernist Vekllei, not even the atomic age has been able to dispense with its hard-worked pragmatism developed in a millennia of bitter cold.

2031 Apartment Diagram #

📖 Published 15th May 2020 | Read here.

Baron had inherited the apartment from his uncle, who passed in the year following his parents. It was in a mixed residential-industrial neighbourhood, adjacent to a canvas factory. Out back was a rivulet, which roared in the long rainstorms of early April.

Each January, the Colour Bureau of the Architecture Assembly announces the year’s colours, and tradition in mainstream architecture and interior design is to incorporate the announced palettes, which usually contain a hundred or so colours. His uncle’s apartment had been built and furnished in 2031, and so it had a #2031 Colour Profile.

In some ways, it was a very conventional apartment in the Vekllei tradition. It had a sauna and bath in the wetroom, a bidet, a sunken living room and a bread oven. In others, it was more peculiar. The apartment was bizarrely allocated across three levels. You alighted the entrance light well into a sunken living space, then climbed back up into the kitchen. The main living room and master bedroom were another step above the kitchen. Adjacent to the main living area was a closet and study, which overlooked the entrance from a half-meter mezzanine.

It was in this study that Tzipora set up shop when she arrived in March 2063. Baron had been reluctant to take her even provisionally, not least because it would mean searching for a new apartment in his busy return period after being abroad for ten years. Tzipora, however, had lived in a dormitory for much of her life and had settled in the alcove once she acquired a dresser screen. She refused outright the master bedroom, which sparked a sleepy agoraphobia. By the time Baron had made other accomodations, Tzipora had entrenched herself in the neighbourhood and had developed a severe sentimentality about the apartment and its rivulet, and so that was where he lived for the rest of his life.

In this sense, Tzipora had a strange kinship with the apartment. Baron sealed himself off in the master bedroom each night, but she never left the main living space. It was warm in there, especially in the flickering light of the enormous oven and fireplace, and when she moved the screen aside in the morning her little corner became part of the living area.

She had a lot of good memories of that apartment.

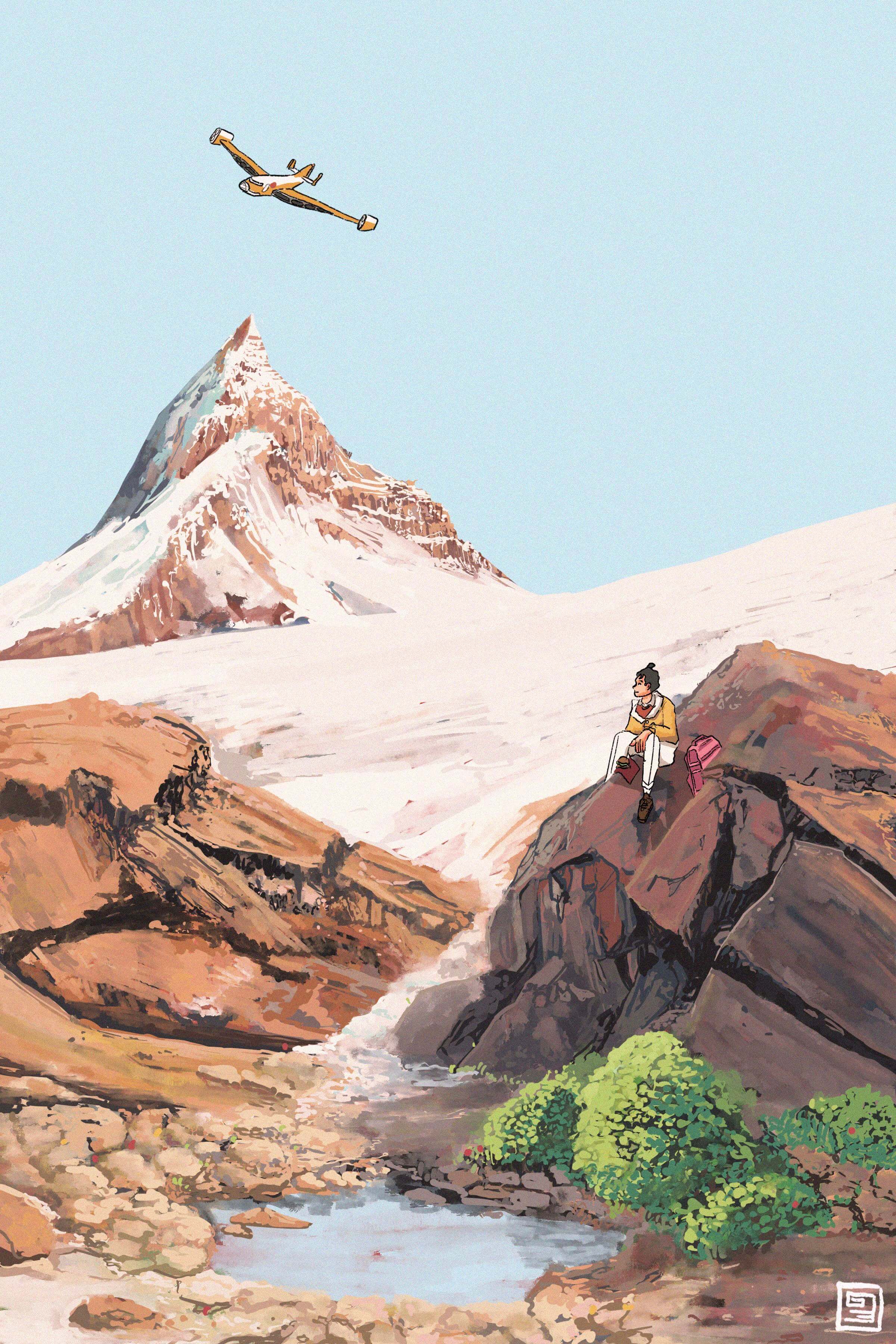

Fiery Peaks #

📖 Published 7th May 2020 | Read here.

After three days in Ada, Tzipora set off towards Mt Miya. She made good time, and after three hours had happened upon the shoulders of the bright Volouisnesnkull Glacier. It was about here that she heard a morbid industrial siren, echoing up the valleys from far away.

At first she thought it might have come from Ada, since Boya Chemical had a large plant there, but as she lay out her things for lunch she heard the distinct whine of a turbojet. It grew louder, and deeper, until a National Fire VTOL tanker roared across the sky, swirling powdered snow on nearby peaks as it arced across the glacier. It was close enough to catch the sun ablaze in the reflection of its glass nosecone.

She later learned that lava streams had opened up not far from where she’d hiked, and had been making their way towards a geothermal power plant nestled in the highlands. In the evening, on her way back, she saw a long line of fire supertankers and pumpers spraying water in beautiful arcs, where it caught hisses from bright streams of melted rock. It was a common enough sight in Vekllei — hoses were the only defence you could reasonably make against the the fracturing earth.

Still, it was not often you saw jets flying so low. It was funny to her that even the barren glaciers were tamed in this age.

The Chemical Feast #

📖 Published 6th May 2020 | Read here.

East of Montre, West of Tjornes, waits a rare sight among Vekllei’s hard igneous slopes — a crown of gentle sedimentary cliffs packed with ruddy sandstone, which melt glacially into the sea chasing blue-sky bergs.

Tzipora was, at the time, making her way on foot from Montre-Lola to Ada, which was a coastal town in the North-East known for its luxurious health spas. Tzipora was not much interested in health, but she was interested in walking, and she made a pilgrimage along the coast every few years to make sense of the world. She was going whichaway and destined for nowhere in particular. Tzipora was very much Baron’s daughter, in the end.

She had stopped to see the Red Cliffs forty kilometres out from Tjornes when she saw a cruiser of the constabulary parked unusually by the shore. The constabulary were not local police — they were a national outfit tasked with policing government and “bureau business”. You found them at power plants, outside universities, guarding the prime minister and providing bodies for HO/NI (Home Office at National Intelligence) when they needed doors kicked.

Tzipora was not the sort of girl to be intimidated by a badge, and she wandered innocently to the shore where she found the cruiser empty. She looked across a beach of black sand and saw some sort of operation playing out — there was a gun boat not too far from the shore, and a police hydrofoil beached on the sand. She counted maybe a dozen officers. She wondered if they’d arrest her if she walked down to see what was happening. She climbed onto the hood of the cruiser to get a better look. Perhaps it was immigrants — or smugglers.

It only took another moment to spot the smashed crates broken across the rocks before she knew what was going on. She was witnessing the dying days of the countercultural decade, and its chemical fuel was now smashed open before her.

The 2070s were a wild time for the so-called “pink years” in Vekllei, and for the first time in Tzipora’s memory she started seeing “pleasure drugs” on the streets. There had always been plenty of sin carrying on in Vekllei, even in her early days — hallucinogenics, alcohol, and synthesised highs were legal and easy. But you didn’t see much of the exotic stuff, which grew in a better climate. Hash, coke, H — it was all underground stuff for personal use. These drugs were listed among many others in the class-A import prohibition orders, which made them hard to find and illegal to import. These were “pleasure drugs” — the Vekllei phrase for overseas narcotics that didn’t have a place in Upen or a preexisting cultural history. Comparatively, they were just ‘for pleasure’.

H for heroin was a big news item for a long time, and with it you had one the largest moral panics in modern Vekllei cultural memory. Crackdowns came soon after. Tzipora found it difficult to describe the feeling of the time. It was a new generation — one she didn’t belong to, despite her appearance — and she didn’t have much sympathy for hedonists. They might tell her different, but she never thought the pink years were about much more than feeling good all of the time. She wondered if she was growing old and grumpy inside.

She wondered how the crates had got there. Had the coast guard sunk another smugger? You heard about the navy firing shots in the news sometimes.

Ruined with seawater and picked over by constables, the chemical feast of Vekllei’s pink years died with the times. Tzipora wouldn’t miss it.

She stepped off the hood and set off back towards the road, where a warm inn and hot food awaited her.

The Trials of Cobian #

📖 Published 2nd May 2020 | Read here.

According to her friends, Tzipora’s contemporary afflictions were tragic. Her medical problems; her violent childhood; her sensitivity and melancholy — you could feel sorry for her, because a lot of her problems were not her fault. She invoked sympathy. Tzipora never considered herself particularly tragic. It seemed straightforward, if difficult; she continued to live — and so she lived. Tzipora’s sympathy was instead reserved for her first and closest friend: Cobian.

Cobian was not well-liked at school, and it did not take long for Tzipora to find out why. She had a childish edge for a sixteen-year-old, and bitterly hated losing. She was not good at school or sports, was not particularly charming, and came across as desperately lonely. She was a quiet misandrist, which would have been fine if she could play the part of a self-assured social matriarch, but her mother’s despotic conservatism struck out that possibility early on. Such is life.

And because her world was predicated on being liked and living a normal life, her psyche prohibited self-reflection. That was the great difference between Cobian and Tzipora. They may both have been young and neurotic, but Tzipora’s relentless self-interrogation left great space for personal growth. Cobian was instead trapped in a domestic play-fantasy, in which she could live out a mythical high-school life, and shattering that illusion would collapse her whole reason for being.

Tzipora recalled visiting Cobian’s home for the first time. Cobian’s mother asked Tzipora to remove her shoes and socks and wash her feet before going to play inside. By the time Tzipora found Cobian in her room, the girl had already changed and handed over her uniform to be laundered. Tzipora, in her tomboyish indigence, had never encountered such a brutally hygienic regime.

Cobian was a different girl at home. Her anxiety and neurosis washed out a little, and her confidence was propped up by the routines her mother had set out for her since she was a child. There was a friendly, curious girl buried under a decade of loneliness.

Tzipora wondered what Cobian thought about lying in bed at night, and why the girl worried so much about things that didn’t matter. And it was precisely in the smallness of those things and the tremendous anxiety Cobian owed toward them that made Tzipora want to hug her. To be so worked up over something so pathetic was startlingly moving. The idea that the girl had deluded herself into a corner of hopelessness seemed sad — and the fact that no one would reasonably care about such a feeble, meaningless, self-inflicted state of affairs made it tragic.

Through Tzipora’s friendship and the world it opened up for her, some of Cobian’s edges were sanded down. Some of it was a late maturity — some of it was Tzipora’s dismantling of the scaffolding the girl’s mother had shoved in there. With that effort, and obvious love, Cobian’s reason for being changed too. One day, in Tzipora’s presence, it didn’t seem so important to be liked by everybody anymore.

V. The Book Club #

A Cashless Tokyo #

📖 Published 28th December 2018

✿ Note from the Editor This essay was published on the original Vekllei site in February 2019. Since it will not be coming back, it is being reprinted here in a desperate attempt to fill out this issue. Yes, it’s painfully self-concerned and a little painful to read back, but for newcomers to the project you might find some “obvious truths” about Vekllei you have not yet encountered.

I did not come to Tokyo to find a reference for the Petticoat Project, because utopia does not exist there for me. In fact, by nearly every Vekllei metric, Tokyo is positively dystopian — a consumer paradise of the crushing, isolating modernity Vekllei is supposed to escape. And yet, marks of this city (and this country) are prevalent through Vekllei as a constructed country and my aesthetic as a writer and an artist. I can’t bring myself to love all of Japanese society, but I do love the country and its people. This intersection between traditional utopian world-building (along the lines of News from Nowhere or even the original Utopia) and the emotional, linear fragments of utopian storytelling which realise the cold encyclopaedia of a utopian world were the focus of my expedition to Japan. The premise of Vekllei society is at odds with so much of Japanese society — yet the emotional, aesthetic culture of the country (what I call the ‘character’ of utopianism) has influenced my media creation tremendously.

As a supplementary preface, I would like to note that it would be terrible of me to dismiss Japan as an oriental wonder of salarymen and neo-Zaibatsu. That approach has more in common with Frank Capra’s wartime propaganda piece Know Your Enemy: Japan than it does with real structural criticism. It is all too easy to dismiss the social and economic conditions of the country today as the natural inclination of a Japanese caricature — a homogenous hive-mind of enormously productive and obedient people. This is of course a terrible attack on the proud and long-standing tradition of dissent and progressiveness in the country — which is also home to one of the world’s largest opposition communist parties. It is a country of student mobilisation, protests and intense factionalism between the left and right-wing radicals (Andrews, W., 2016). It is important not to conflate the impersonal structures of a society with the orientalist idea of cultural predisposition.

A love of Studio Ghibli films and a desire for material and emotional escapism is what drives my utopian world-building. Where co-founder Isao Takahata had a penchant for artful emotional realism and domestic drama, Hayao Miyazaki has found tremendous success in Japan and abroad with his fantastical stories rich with nostalgia and warmth. They have obvious recurring themes — childhood, environmentalism, aircraft, etc., but it is no real secret (at least to media critics and Ghibli superfans) that these overt recurrences are symptomatic of more serious and grounded beliefs. In a fantastic analysis of My Neighbour Totoro, Phillip E. Wegner makes use of Kojin Karatani’s works (another great influence of mine) to illustrate Miyazaki’s uniquely Japanese pre-Meiji cross-generational nostalgia evident in the film.

What Miyazaki presents us with in My Neighbor Totoro is a vision in which the classic “what if” question of the genre has been proposed: that is, what if the Meiji revolution did not happen? Moreover, since it is the dramatic and rapid modernization of the Meiji period that gives rise to the virulent imperialist nationalism and militarism that ultimately results in the Second World War, Miyazaki also offers in his film us a glimpse of a Japan in which the catastrophe of World War II did not occur (Wegner, P.E., 2010).

Japan’s spectre of modernity is a recurring character in many of Miyazaki’s films, just as the villain of war revives itself time and time again — from the steel production of Iron Town in Princess Mononoke to the death of the golden age of aviation in The Wind Rises. Karatani’s landmark work, Origins of Japanese Literature, makes clear that basic premises of modern society — from children to history to nature — are not immutable items atomised by scientific fact, but instead products of modern society that have not always existed (Karatani, K., 1993. pp. 12-44, 113-135). Vekllei reflects this concept, at least superficially — children are represented as independent agents desegregated from modern age-based schooling, nature is regarded as a fellow social organ, and work is largely self-satisfying and decommodified. These are things that are important to me and it makes sense enough that Vekllei reflects that.

Similarly, even supposedly less political Ghibli films like Kiki’s Delivery Service carry powerful images of the ‘spectre of modernity’. Regarding the climax of the film in which a zeppelin soars hopelessly out of control over a city, A.J. Rocca hauntingly writes:

[We] find that this is not truly a witch’s story, but a ghost story. The ghost died in a fire on 6 May 1937, foreshadowing the fires of a war that would change the world forever. The ghost is called the Spirit of Freedom in the film, but its true name is LZ 129 Hindenburg, and it’s not the spirit of freedom but the ghost of modernity (Rocca, 2017).

So the material manifestation of Japanese society for me— despite all the glory of her bright packaging and dense infrastructure — is an aesthetic and satirical media culture that saturates the Petticoat Project. Vekllei is a ‘poor man’s Utopia’, inspired in part by my superficial understanding of a ‘poor man’s Japan’. Vekllei, like media representations of postwar Shōwa Japan, has a shadow of pacifism and shame about it (that idea that ‘all politics is sexual pathology’ occurs to me). These are deliberate aesthetic choices that reflect not landscape utopianism but character utopianism — the real colour of a constructed world that acts out the structure of mean ideology and culture-constructs. These ill-defined images of utopian society, and a rejection of landscape world-building, are excellent vehicles for utopian writing. After all, it is sustained engagement with utopia that betrays the totality of it (Wegner, P.E., 1998). What fascinates me particularly about Miyazaki’s unique utopian instincts is his recurring premise is essentially nostalgic and escapist — the aesthetic of a Miyazaki film is almost always midcentury or earlier, illustrating a time before Japan’s ‘modern century’. This is in stark contrast to the saccharine optimism of utopian socialists like Morris, Chernyshevsky, and Bellemy, telling stories of a future yet to come.

And that is to say nothing of the aesthetic qualities of a Japanese city! Tokyo is a wonderful glimpse of a retro-future as imagined by the 1980s — as though the economic crisis of the 1990s has since suspended time. Japan is clean and modern, but also retrofuturistic. The lifeblood of the city is in rebar and concrete as infrastructure. The people on the street are dressed in conservative items that go without the prudish connotations of similar Western fashion. Working men and women are suited traditionally, many with waistcoats. Such is the visual language of modern Japan. Young men sport tech-wear or innovative types of street-wear dominated by colour and comfort. General women’s fashion leans heavily on items popularly discarded in Western markets, at least until recently. Pleat or patterned skirts, blouses, cardigans, hosiery and socks, loafers and brogues, etc. are very common and provide a wonderful anecdotal rebuff to the outrageous images of ‘Harajuku girls’ and Lolita style that epitomise some ideas of Japanese fashion. The famous ‘sailor uniform’ has been largely phased out of junior and senior high schooling, replaced with Western-style blazers and ties. Tokyo is not ‘behind’ the rest of the world; that is not what it means to be retrofuturistic. In my eyes, it has disembarked from Western technological and fashion attitudes some time ago and has since progressed on its own collective cultural intuition, and has subsequently spent the last few decades exporting media, fashion and culture into the West. It’s a great thing to see in person, at the heart of it all.

Despite my qualms with modern Japanese consumer society, Vekllei is perched on a romanticised and fictitious Japanese aesthetic, and the country is enormously influential on the way I go about world-construction. With one sentence I will denounce the complexity of Japanese honorific language systems and in the other fawn over the mixed agricultural-residential suburbs that make up so much of the land outside of Tokyo’s city limits. Koka parks were inspired by these displays of community food production. The Vekllei Constabulary were created after research and experience with the Japanese Police Box system. Vekllei’s knotted network of trains and streetcars are reminiscent of Tokyo and Hiroshima. For all my public rejection of modern consumer society, and my begrudging participation in it, the Japanese qualities of Vekllei are valuable and are utopian in their own right — and so Tokyo remains one of the most important inspirations of Petticoat Society in the world.

So what of that dichotomy? Of deep ideological incongruities with Japanese consumer society, but an embarrassing affection for the mythological post-war aesthetic and Japanese culture? The truth of it is that Vekllei is first and foremost a collection of stories, and stories are the domain of the emotional. Wonderful, vague images of utopia — like washing corn in My Neighbour Totoro or an all-night writing session in Whisper of the Heart. My time in Tokyo introduced me to a wealth of these nostalgic feelings — of curiosity in a cauldron of social atomisation. Life in Tokyo is not without problems, and it is certainly not my perfect idea of utopia, but the intersection of the culture and promise of Japanese society, either in the past as alt-history or in the future as science fiction, has me coming back time and time again to better realise my own projects of utopia.

Works cited above:

Andrews, W., 2016. Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture from 1945 to Fukushima. Oxford University Press.

Karatani, K., 1993. Origins of modern Japanese literature. Duke University Press.

Rocca, A. (2017). Miyazaki’s Haunted Utopia: The Ghost of Modernity in 'Kiki’s Delivery Service'. [online] PopMatters. Available at: https://www.popmatters.com/miyazakis-haunted-utopia-ghost-modernity-kikis-delivery-service-2495410503.html [Accessed 24 Dec. 2018].

Wegner, P.E., 2010. " An Unfinished Project that was Also a Missed Opportunity": Utopia and Alternate History in Hayao Miyazaki's My Neighbor Totoro. ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, 5(2).

Wegner, P.E., 1998. Horizons, Figures, and Machines: The Dialectic of Utopia in the Work of Fredric Jameson [with Comments]. Utopian Studies, 9(2), pp.58-77.

VI. Gallery #

This month’s sketches, presented without context or or standards of quality. Contact Hobart at [email protected] for full-res versions of any images received in this bulletin.

Cat [28.5.2020] #

Redhead [24.5.2020] #

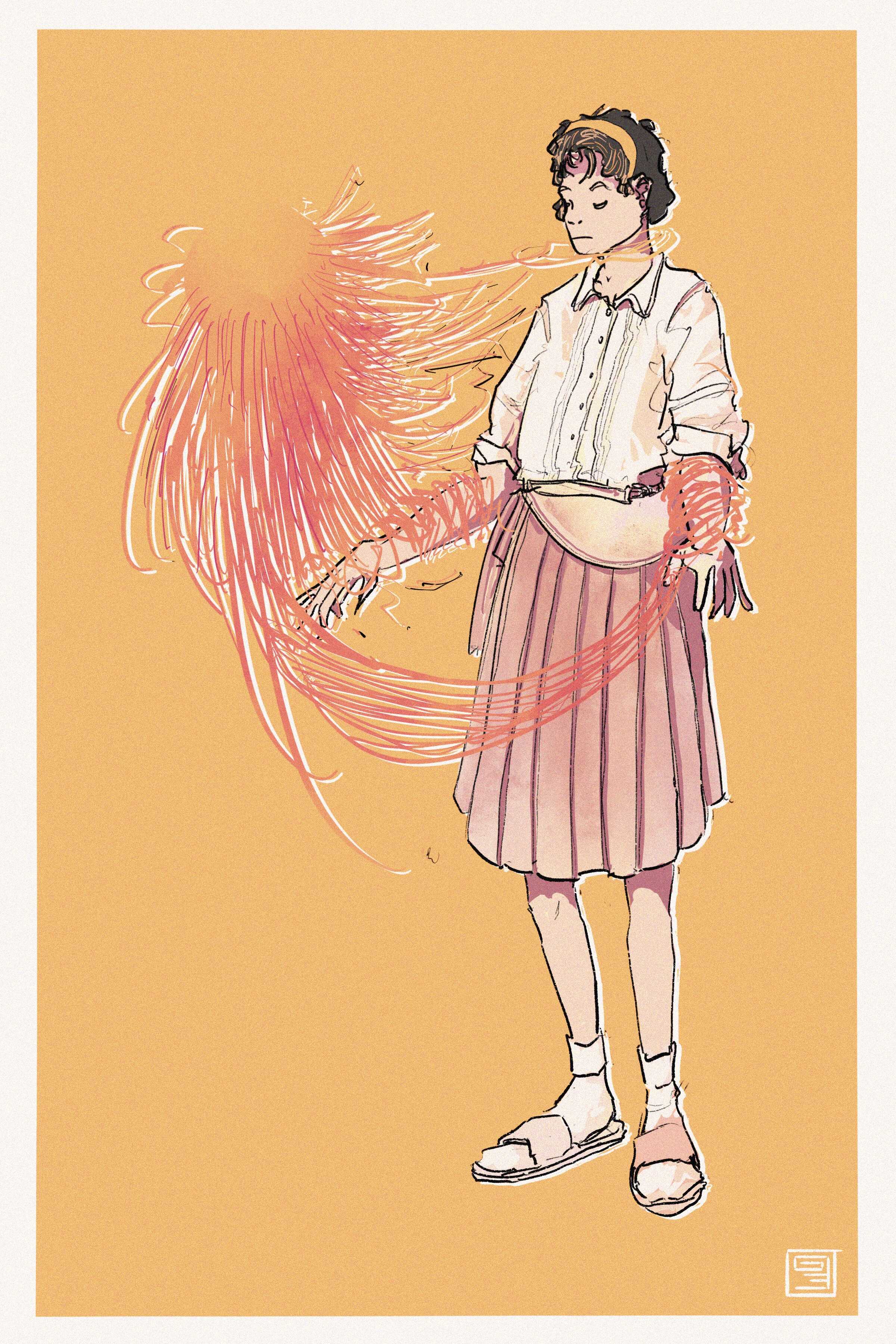

Spirit [18.5.2020] #

Salt Nip [7.5.2020] #

Published by MillMint Press. Copyright 2020. To stop receiving these emails send UNSUBSCRIBE to [email protected].