NEW Story: Sunday Morning

The Commons System

Read more: A Social Economy

The commons is Vekllei’s domestic moneyless economy. It is perhaps Vekllei’s most enigmatic and celebrated national feature, and distinguishes the country from all others. Vekllei people are generally very aware of their unique circumstances and are not uncritical or completely satisfied – nonetheless, the commons could not work without their effort and enthusiasm, and its ongoing success testifies to the comfort and dignity it has brought Vekllei people across the Atlantic.

The Vekllei economy exists in two pieces: as a services market, dominated by wandering interest and cooperation, and as an industrial market, which comprises the bulk of manufacturing and planned production.

While a social economy has social forms, and the economic psychology of the commons is discussed elsewhere on this site, it has tangible, conventional and straightforward economic logic. This article illustrates the commons as an economic engine.

Economic Structure #

The basic logic of the commons separates goods from services – goods flow continuously through automated production and retail distribution. Services requiring human effort flow through participatory access gates that distinguish employed from non-employed residents.

The commons operates as an industrial economy with rigorous accounting, conducted without wages touching workers or prices touching consumers. Understanding how this functions requires examining the productive machinery itself.

Industrial Production & Pricing #

Vekllei produces approximately ⟁2.8 trillion in accounted annual output across its bureau system and private corporations. This represents real calculations used for planning, trade and capital allocation rather than fictional value. Accounted Revenue is established through a financial calculation known as Accounted Value.

Accounted value ($\text{A.V.}$) derives from several inputs. For automated bureau production, the formula represents:

$$\text{A.V.} = \left(L_h \times S_f\right) + C_r + \left(M_r \times \lambda\right) - \left(E_g \times \alpha_e\right)$$

Where:

- $L_h$ = Labour hours (tracked regardless of payment)

- $S_f$ = Skill factor (1.0 to 5.0 based on expertise), calculated as: $$ S_f = 1.0 + \left(\frac{I_t}{I_{\text{base}}}\right)^{0.7} + \left(\frac{Q_t}{Q_{\text{ref}}}\right)^{0.5} $$

- $I_t$ = Total investment in training (education, apprenticeship, certification)

- $I_{\text{base}}$ = Baseline training investment (⟁120,000)

- $Q_t$ = Average queue time for this skill across all republics

- $Q_{\text{ref}}$ = Reference queue time (48 hours)

- $C_r$ = Replacement reserve contribution

- $M_r$ = Raw material extraction/refining cost before scarcity adjustment

- $\lambda$ = Scarcity multiplier, determined by: $$ \lambda = 1.0 + \left(\frac{R_g}{R_{\text{avg}}}\right) + \left(\frac{D_s}{S_a}\right) $$

- $R_g$ = Geological rarity index (0-2.0)

- $R_{\text{avg}}$ = Average rarity for common materials (1.0)

- $D_s$ = Sector demand competing for this material

- $S_a$ = Available supply

- $E_g$ = Efficiency gains from automation (labour hours saved, defect reduction)

- $\alpha_e$ = Efficiency penalty multiplier (starts at 1.0, increases with poor performance): $$ \alpha_e = 1.0 + \left(\frac{M_h}{M_{\text{expected}}}\right) + \left(\frac{F_r}{F_{\text{target}}}\right) $$

- $M_h$ = Actual maintenance hours required

- $M_{\text{expected}}$ = Expected maintenance hours for this equipment

- $F_r$ = Failure rate (defects per thousand units)

- $F_{\text{target}}$ = Target failure rate

External commodities are useful as a price anchor because Vekllei exists in a competitive international market, and subsequently a global market can be a tool for rational planning. Using this formula, the country acts as a sovereign economic agent engaging in its own economic behaviour as an individual would.

Example:

| Component | Calculation | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Contribution | $L_h$ × $S_f$ = 100 × 3.849 | 384.9 |

| Capital Depreciation | $C_d$ | 500 |

| Scarcity-Adjusted Material Cost | $M_r$ × $\lambda$ = 2000 × 4.5 | 9000 |

| Efficiency Penalty | $E_g$ × $\alpha_e$ = 20 × 4.75 | 95 |

| Accounted Value (A.V.) | Sum above: 384.9 + 500 + 9000 - 95 | 9789.9 |

The Vekllei industrial crown (⟁) maintains a managed float against major foreign currencies, primarily anchored to the British pound and US dollar through Commonwealth foreign exchange reserves. This exchange rate provides the reference point for calculating accounted value of imported materials and export revenues.

When Vekllei imports raw materials or finished goods, the purchase price in foreign currency converts to accounted value at the prevailing exchange rate. A tonne of copper purchased for $8,400 USD converts to approximately ⟁12,600 at typical exchange rates (⟁1.50 per USD). This accounted cost then flows through domestic production calculations, creating coherent value chains from imported inputs through to finished products.

For domestically produced goods with no international trade comparisons, planners use constructed reference prices based on comparable traded goods, labour content and material composition. A uniquely Vekllei cultural product like traditional Oslolan textiles might be valued by comparing labour hours and material costs to similar artisan textiles that do trade internationally, adjusted for skill differentials and material scarcity.

The value of $S_f$ is set by companies and municipal corporations participating in the industrial market rather than a central planner, which determines the support provided by the relevant accounting system. Overestimating, or ‘overpricing’ the skill factor in a company will make its products more expensive and less competitive in this formula, and affect investment. Companies in the industrial economy are forced to rationally price their abilities ($S_f$) or face ruin.1

The Commonwealth National Economic Register maintains a reference catalogue of over 400,000 product categories with constructed valuations. When a new product emerges – say, a novel electronic device produced only in Vekllei – accountants decompose it into constituent elements (labour hours by skill level, material inputs, capital equipment used) and aggregate these into initial accounted value. As the product enters use and consumption patterns emerge, the valuation adjusts based on observed demand signals and resource allocation decisions.

A textile company producing 2 million shirts annually might calculate:

| Input | Quantity | Unit Value | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour (automated) | 2,400 hrs | ⟁45/hr | ⟁108,000 |

| Labour (human oversight) | 800 hrs | ⟁120/hr | ⟁96,000 |

| Capital depreciation | Annual | — | ⟁340,000 |

| Cotton (imported) | 450 tonnes | ⟁800/tonne | ⟁360,000 |

| Dyes and chemicals | Various | — | ⟁45,000 |

| Total Accounted Cost | ⟁949,000 | ||

| Output Value | 2M shirts | ⟁0.62/shirt | ⟁1,240,000 |

| Accounted Surplus | ⟁291,000 |

This surplus is used in a variety of ways:

| Use | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Reinvestment | 40% |

| Federal redistribution | 25% |

| Export currency | 20% |

| Reserve accumulation | 15% |

This surplus does not become profit extracted as wages. The accounting remains real even whilst money never circulates to individuals. This allows sophisticated planning, international trade and capital allocation whilst maintaining domestic moneylessness.

Demand Signal Processing #

The commons processes demand through continuous inventory tracking rather than price signals. Retail distribution centres across all republics report stock levels and depletion rates to regional accounting bureaus, which aggregate into the Commonwealth National Economic Register.

In the industrial economy, inventory velocity generally determines production adjustments. Products depleting within 48 hours signal underproduction. Items remaining on shelves beyond two weeks signal overproduction. The system tracks consumption patterns anonymously through aggregate flows rather than individual surveillance, respecting privacy whilst gathering necessary planning data.

Production targets adjust quarterly using the formula:

$$P_{t+1} = P_t \times \left(1 + \alpha \times \frac{D_a - S_a}{S_a}\right)$$

Where:

- $P_{t+1}$ = Next quarter production target

- $P_t$ = Current quarter production

- $\alpha$ = Adjustment sensitivity (0.15 for staples, 0.30 for consumer goods)

- $D_a$ = Actual consumption (units distributed)

- $S_a$ = Available supply (units produced)

A textile company producing 2 million shirts quarterly with consumption at 2.3 million would calculate:

$$P_{t+1} = 2{,}000{,}000 \times \left(1 + 0.20 \times \frac{2{,}300{,}000 - 2{,}000{,}000}{2{,}000{,}000}\right) = 2{,}060{,}000$$

This increases next quarter production by 3%, responding to demonstrated demand without requiring price increases or shortages. The system operates continuously across all product categories, with regional variations tracked separately to prevent urban demand patterns from starving rural areas.

Seasonal adjustments and trend detection modify base calculations. Winter clothing production increases in autumn, swimming equipment in spring. Multi-year trend analysis identifies shifting preferences – declining demand for certain textiles, increasing interest in outdoor equipment. Bureau planning committees receive quarterly reports showing these patterns across their sectors.

Public Coordination & Development #

Read more: State Industry in Vekllei

Public Participants in the Market

This is a list of the government offices involved in Vekllei’s national economy. You can read more about them by clicking on their parent bureau.

- Bureau of Economic Participation

- Universal Economic Service

- Disability Economic Service

- Rural Economic Service

- Work Accessibility Development Board

- Community Economic Work Programme

- Economic Accommodations Programme

- National Contributions Assessment Panel

- Bureau of Economic Weather

- Commonwealth Observatory of Economics

- Regional Economic Signals Network

- Supply Patterns & Behaviours Service

- Commonwealth Automatic Electric Economic Warning Network

- Economic Resilience Commission

- Economic Crisis Council

- Bureau of Industrial Coordination

- Commonwealth Industrial Coordination Council (CICC or Chick)

- National Enterprise Commission

- Industrial Democracy Research Centre

- Cooperative Development Trust

- Bureau of Materials and Supply

- Resource Planning Commission

- Commonwealth Materials Board

- Industrial Supply Network

- Strategic Supply Reserve

- National Resource Laboratory

- Commonwealth Minerals Registry

- Bureau of Residences and Factories

- National Construction House

- Municipal Planning Commission

- Municipal Enterprise Commission

- Municipal Infrastructure Construction Corporation (MICC)

- Bureau of Surplus and Export

- Commonwealth Export Licensing Scheme

- International Trade Service

- Commonwealth Aid (BSE Office)

- Production Merits Commission

- Market Supply Commission

- Commonwealth Trade Missions Service (CTMS)

- Bureau of the Commons

- Commonwealth Supply Commission

- Commonwealth Logistics Service

- Commonwealth Industrial Coordinators

- Commonwealth Central Inventory

- Panveletian Trade Commission

- Quality of Life Surveillance Commission

With 2,400 constituents of bureau industries and 18,000 companies operating without price coordination, the commons controls overproduction or underproduction through several mechanisms.

-

Enterprise Secretaries, economists in the employ of Regional Commonwealths meet quarterly within each major bureau. Representatives from member companies review aggregated production data, consumption patterns and inventory levels. They don’t command individual companies but facilitate information sharing and voluntary coordination. If twelve textile companies all plan expansion simultaneously, a secretary highlights potential overcapacity.

-

Regional Production Balancing occurs through advice from the Bureau of Economic Weather and the Bureau of the Commons industrial coordinators who track production across multiple bureaus within their territories. The Kalina Commonwealth coordinator might notice three sugar refineries planning simultaneous capacity increases whilst clothing manufacturers report declining activity. They facilitate discussions between sectors and might suggest resource reallocation.

-

Federal Reservation provides a coordination mechanism. When critical materials face scarcity, the Ministry of Industry allocates supplies through priority systems. Essential goods (food, medicine, housing materials, etc.) receive first allocation. Export production receives last priority. This prevents coordination failures from creating genuine hardship.

-

The Commonwealth National Economic Register is a networked computer system that aggregates data continuously, identifying emerging coordination problems before they manifest as shortages or gluts. Computer patterns trained on decades of production data flag anomalous behaviour – unusual inventory accumulation, unexpected depletion rates, regional imbalances, etc. Human planners receive alerts for investigation.

This creates what economists call “visible hand” coordination; active but decentralised management replacing price signals with information flows and voluntary cooperation.

Domestic Trade #

The Commonwealth’s eight Regional Commonwealths use the industrial crown (⟁) for inter-republic trade, creating an internal foreign exchange system. Republics maintain trade balances with each other, tracked through Regional Commonwealth accounting bureaus.

Exchange Rate Management prevents currency manipulation through several mechanisms:

$$E_{r1,r2} = E_{\text{base}} \times \left(1 + \beta \times \frac{B_{r1,r2}}{T_{r1,r2}}\right)$$

Where:

- $E_{r1,r2}$ = Exchange rate between republics

- $E_{\text{base}}$ = Commonwealth baseline rate (1.0)

- $\beta$ = Balance sensitivity factor (0.05)

- $B_{r1,r2}$ = Trade balance between republics

- $T_{r1,r2}$ = Total trade volume

Persistent trade imbalances automatically adjust exchange rates, making exports from surplus republics less attractive and imports more expensive. This creates self-correcting pressure toward balanced trade.

-

Federal Deposits supplement exchange rate adjustments. The federal government maintains a Federal Reserve (⟁12 billion annually) that flows toward republics running persistent deficits. Oslola and Kairi, as industrial powerhouses, effectively subsidise smaller republics through this mechanism.

-

Production Licensing prevents beggar-thy-neighbour competition. Republics cannot arbitrarily devalue their internal accounting to undercut each other. The Commonwealth National Economic Register maintains standard accounted value calculations across all republics. A shirt produced in Barbados receives the same base valuation as one from Oslola, preventing artificial competitive advantages.

This system acknowledges that Vekllei’s geographic dispersion creates genuine economic differences between republics whilst preventing these from fragmenting the commons into competing economic zones.

Automatic Production #

Read more: Automatic Allocation

Vekllei’s automation reflects inverted economic logic. Labour carries no direct cost, which transforms the deployment calculation:

$$A_v = \frac{L_f}{C_c + M_c} \times R_f$$

Where:

- $A_v$ = Automation value

- $L_f$ = Human labor hours freed

- $C_c$ = Capital costs

- $M_c$ = Maintenance costs

- $R_f$ = Redeployment factor (value of freed labor in new roles)

Automation becomes justified – although imperfectly policed – when it frees human capacity for better uses rather than when it proves cheaper than wages. A street-sweeping robot costing ⟁240,000 that eliminates 4,000 annual labour hours becomes economical when those hours redeploy to work generating more than ⟁60/hour in accounted value.

Current automation penetration by sector:

| Sector | Automation % | Human Role | Annual Investment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Manufacturing | 94% | Oversight, maintenance | ⟁340M |

| Food Processing | 89% | Quality control, recipes | ⟁180M |

| Logistics & Distribution | 78% | Exception handling | ⟁290M |

| Agriculture | 71% | Specialised cultivation | ⟁150M |

| Construction | 45% | Skilled trades, design | ⟁420M |

| Healthcare | 23% | Diagnosis, procedures | ⟁190M |

| Education | 12% | Administrative only | ⟁45M |

| Personal Services | 8% | Minimal | ⟁30M |

The pattern shows clear progression: anything that can be automated receives automation investment. This develops excellent productivity in goods production whilst preserving human effort for services that genuinely require people. Because Commonwealth enterprise cannot rely on a captive pool of cheap labour, it necessitates a constant process of automation and upskilling.

Bureau & Corporate Economics #

Read more: Economic Productivity in Vekllei

The bureau system comprises approximately 2,400 major productive organisations across Vekllei’s republics, supplemented by roughly 18,000 private companies and municipal corporations. These function as worker cooperatives or private enterprises operating within federal planning frameworks, though their character differs significantly.

The state has substantial but minority participation in the overall market, and economic subsidiarity further complicates the foreigner’s understanding of the economy.

Government enterprises handle infrastructure and essential services requiring unified command structures. The national railway, electrical generation, water systems and telecommunications operate as direct government enterprises with civil service employment. These organisations prioritise reliability and universal service, but do not necessarily resemble state-owned enterprise overseas – CommRail, for example, is a federation of hundreds of local government railways under a common corporation.

Bureau corporations represent industrial federations controlling entire sectors. Caribbea Cane is made up of dozens of independent sugar cane farms and refineries, both private and public, under unified planning. These bureaus emerged from postwar reconstruction when scattered private firms required coordination to achieve industrial scale. Bureau membership provides access to federal capital allocation, export licensing and standardised technological development. Individual companies maintain operational autonomy whilst coordinating production volumes, quality standards and technological advancement through bureau congresses.

Municipal corporations represent intentional industrial communities organised around specific production. They are closely associated with the ludic economy and resemble the kibbutz model, where housing, work and community life integrate into coherent social structures. A municipal textile corporation might include housing for 20 families, shared dining facilities, childcare services and integrated textile production. Residents participate in both production and community governance through municipal assemblies, creating tight social bonds around collective enterprise. Municipal corporations typically produce for local or regional markets rather than export, though some larger operations achieve significant industrial scale.

Private companies operate independently outside bureau structures, typically in specialised production or local markets (but not always; Vekllei has several major private firms). A private furniture workshop might employ thirty workers producing custom pieces for local markets. These companies access commons labour and materials through the same mechanisms as bureaus but lack coordinated planning and federal capital access. Many export-focused private companies eventually join bureaus to access technological development and capital investment, though some maintain independence to preserve operational flexibility. They may have municipalist or familial communal social structures, or operate like conventional private enterprise overseas.

Employment distribution (approximate):

| Employer Type | Employment Share | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Federal/Republic Government | 18% | Stable, bureaucratic, lifetime careers |

| Bureau Corporations | 24% | Large cooperatives, industrial production |

| Private Companies | 31% | Varied sizes, often export-focused |

| Municipal Corporations | 12% | Local services, community-focused |

| Independent/Self-Employed | 15% | Cafés, craftspeople, professionals |

Bureau and corporate revenue for fiscal year 2063 (in billions ⟁):

| Sector | Accounted Revenue | Capital Investment | Employment | Efficiency Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food & Agriculture | ⟁340 | ⟁48 | 180,000 | 1.89 |

| Textiles & Clothing | ⟁120 | ⟁34 | 45,000 | 1.41 |

| Housing & Construction | ⟁680 | ⟁210 | 340,000 | 1.62 |

| Transport & Logistics | ⟁290 | ⟁125 | 95,000 | 1.16 |

| Manufacturing | ⟁510 | ⟁180 | 120,000 | 1.42 |

| Energy & Utilities | ⟁180 | ⟁95 | 32,000 | 0.95 |

| Services | ⟁340 | ⟁45 | 520,000 | 3.78 |

| Technology | ⟁210 | ⟁110 | 85,000 | 1.24 |

Efficiency ratio calculation:

$$E_r = \frac{R_a}{C_i + L_i}$$

Where:

- $E_r$ = Efficiency ratio

- $R_a$ = Accounted revenue

- $C_i$ = Capital investment

- $L_i$ = Imputed labor costs

Services show highest efficiency through labour intensity and low capital requirements. Manufacturing shows moderate efficiency through aggressive automation. Energy shows low efficiency because infrastructure requires massive capital for modest output.

Goods Distribution #

Goods produced through automated systems flow to residents through retail channels that superficially resemble conventional commerce. Vekllei maintains department stores, shops and markets that function like their foreign counterparts, operating without payment at point of sale.

Retail Operations #

A Vekllei department store presents conventional appearance. Clothing sections, home goods, electronics and cosmetics occupy organised floor space. Staff assist customers, displays showcase products, dressing rooms permit trying garments. Cash registers remain absent.

Residents select desired items and depart. Foreign tourists face different treatment through package rates covering estimated consumption and bag searches upon departure. Residents receive trust because most people naturally self-regulate consumption. Abuse of the system – whether motivated by malice or mental illness – is generally obvious, and penalised under the crime of misdemeanour hoarding.

Average household consumption for a family of three in Oslola:

| Category | Monthly Units | Accounted Value |

|---|---|---|

| Food (grocery) | 120kg | ⟁180 |

| Food (restaurants) | 18 meals | ⟁95 |

| Clothing | 3-5 items | ⟁85 |

| Household goods | Various | ⟁140 |

| Personal items | Various | ⟁65 |

| Entertainment | Variable | ⟁45 |

| Total Monthly | ⟁610 |

Multiplying across 8.9 million households produces approximately ⟁65 billion in annual retail distribution. This remains separate from housing, utilities, transport and services requiring human effort.

Export Privileges #

Once domestic retail demand is saturated, companies may export surplus production for foreign currency through the purchase of export permits.2 This creates incentive structures where productive efficiency generates export capacity rather than profit. Permits are calculated as follows:

$$ E = \begin{cases} 0, & \text{if } P_d < D_d \ \left( P_t - D_d \right) \cdot \pi_e \cdot \left( 1 - T_f \right), & \text{if } P_d \ge D_d \end{cases} $$

Where:

- $E$ = export entitlement (units eligible for export)

- $P_t$ = total production

- $D_d$ = domestic demand saturation point

- $\pi_e$ = export permit conversion rate (cost of purchasing export rights)

- $T_f$ = federal contribution (10% tax on foreign revenue)

A textile company saturating domestic demand with 2 million shirts annually might produce an additional 500,000 units for export. The export revenue (⟁310,000 at international prices) does not flow to workers as wages but generates several benefits through typical distribution patterns:

| Use | Percentage | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Import credits | 40% | Purchase foreign goods unavailable domestically |

| Capital investment | 30% | New equipment, facility expansion |

| Luxury allocation | 20% | Premium goods for company members |

| Federal contribution | 10% | Mandatory tax on foreign revenue |

The luxury allocation provides the key mechanism. Export-successful companies can import foreign goods unavailable in Vekllei: specialised electronics, luxury items, unique products. These distribute to company members based on workplace participation and seniority, creating material incentive for productivity beyond domestic demand.

Workers at export-successful textile companies receive access to the kind of luxuries Vekllei people find highly desireable and unobtainable, including foreign clothing brands, electronic goods from Asian manufacturers, speciality foods and beverages, and premium personal care products. In many cases, these goods are desired not for their immediate utility but their exclusivity and prestige.

To some extent, the export system creates competitive pressure between companies. Workers migrate to export-successful firms offering better luxury allocations. Companies pursue export capacity to retain talented workers. The system maintains productivity incentives without requiring wages or domestic prices.

Participatory Production #

Read more: Ludic Productivity

Beyond industrial systems, small-scale production fills gaps through independent operators. These represent business operations without payment rather than romantic gift economies.

Example

A neighbourhood café operates with apparent normality. The baker arrives, produces pastries, serves customers. People come, consume, depart. No payment occurs, no barter transpires. The baker accesses goods through retail like everyone else. They operate the café in the straightforward psychology of the ludic economy – for its own sake, and the pleasure and prestige it transfers.

The same pattern applies to independent craftspeople making custom furniture, mechanics maintaining personal vehicles, seamstresses doing alterations, musicians performing at venues, and artists producing and displaying work.

Their work is often irregular, diverse and not economically substantial. Yet they play an important role in Vekllei society, and contribute to the fabric of their communities through their presence and self-motivating participation in society, and fill gaps in the industrial economy in an aspirational participatory fashion. There can be material rewards – cafés, restaurants and coffee shops often come up with apartments upstairs, and are centrally located. For a certain type of person interested in a certain kind of lifestyle, this arrangement suits them well.

This sector generates perhaps 15-20% of actual consumption but remains impossible to measure because it operates entirely outside formal accounting. This represents the anarchistic element that makes the commons functional rather than brittle.

Service Access #

Services requiring human effort differ from goods because they cannot be automated and distributed freely – a doctor’s time is limited, and an architect’s expertise proves scarce. The commons facilitates professions of expertise by rewarding them with access to each other.

Employment – or occupation, to use the Vekllei phrase – functions as a binary gate for service access. People are either participating in the commons or they are not. Participation has many uses, and grants access to services through reciprocal systems that rewards your time with the time of others. Unemployment, or non-participation, is anarchic and complex, and often requires negotiation directly with service providers through social relationships.

An occupation is an activity approved and registered with the Commonwealth Employment Register, and involves an eligble method of spending time – it could involve education, caring for children, workplace membership in a company, self-direct economic activity or a justifiable role in the community.

Universal & Participatory Services #

Services in Vekllei are either universal or participatory.

-

Universal services bypass occupation requirements entirely. Emergency healthcare, primary and secondary education, basic municipal services, public transit and essential legal services receive constitutional protection. A non-employed resident receives emergency medical care. Children must attend school. Everyone uses trains and trams.

-

Participatory services require an occupation for commons access: non-emergency medical consultations, housing allocation through the municipal realtor, Commonwealth Airways booking, concert reservations, some restaurants and dining establishments, specialist professional consultations and university priority are all contingent on an occupation. Vekllei is a very social society and being excluded from these systems is highly embarrassing.

The mechanism operates straightforwardly. People who participate access these services through a common network. Unoccupied individuals must arrange them directly through personal negotiation, barter, or remain in queues that prioritise employed participants. Self-exclusion is feasible in Vekllei society, but it is not rewarded.

Housing and Property #

NO REALTORS EXCEPT THE STATE ■ THE COUNTY THE AGENT OF THE STATE ■ THE ARCHITECT THE AGENT OF THE COUNTY

All adults acquire housing through municipal real estate agencies, though the process resembles conventional rental markets with key differences.

Example

A newly arrived immigrant books an appointment with the municipal housing office. They review available housing, typically basic apartments in areas with availability. The immigrant selects from options, signs an occupancy agreement and moves in. No payment occurs, no deposit requires posting – only proof of residency.

Hard work has overlap with the municipality, and someone employed dutifuly for ten years gains advantages. When they seek new housing on the open market in their local area, the republican realtor (removed from the municipality to minimise corruption) prioritises them over non-participating residents and recent arrivals. Among employed residents, seniority provides tie-breaking advantage. This represents simple sorting mechanism rather than a points calculation.

The real shift occurs over time. Property law in Vekllei recognises three competing claims:

- The Steward (the resident)

- The Public (the municipality representing community interest)

- The Sovereign (the land itself with independent standing)

Initial occupancy heavily favours the Public through the municipality. After five years, the Steward’s claim strengthens substantially. After fifteen years, Steward claims typically dominate. After twenty-five years, they become nearly uncontestable. Abuse of the property is safeguarded by the land Sovereign, which “owns itself” under Vekllei law and thus has its own rights determined by dedicated courts seperate from the state.

This is practical ownership through strengthened legal claims rather than formal ownership transfer. A family occupying an apartment for twenty years possesses property in the Vekllei sense through a claim so strong it functions as ownership. They can pass occupancy to children, though children must establish their own employment for service access.

The system creates several effects: housing security increases with tenure, multigenerational housing becomes common, communities stabilise around long-term residents, and property functions without formal sales or mortgages.

Transport & Travel #

Main article: Travel in Vekllei

Local transit operates universally. Trains, trams and buses require no employment verification. Airline travel requires employment for booking.

An employed worker books flights through workplace or municipal systems. Seats allocate based on availability with employed residents receiving priority. A non-employed individual must either negotiate directly with airline workers for standby placement (difficult), travel by alternative means where possible, or remain grounded.

This represents practical rather than punitive logic. Aircraft maintain limited capacity. Flight crews provide labour. The commons prioritises employed participants for services requiring coordinated human effort.

International travel demonstrates this clearly. Employed workers book international flights through normal channels. Non-employed individuals face significant barriers unless they maintain private arrangements or travel by ship (time-consuming and limited).

Labour Mobility & Employment #

Read more: The Work Week

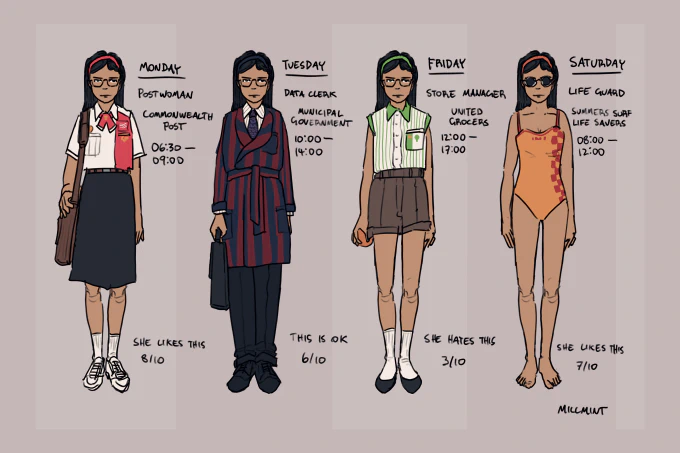

A defining characteristic of Vekllei employment involves mobility. Many workers maintain multiple jobs simultaneously: a lifeguard Monday, a clerk Tuesday, a librarian Thursday and Friday. This represents normal employment practice rather than unusual or stigmatised behaviour.

| Work Pattern | Percentage | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Single full-time | 32% | Doctor, specialised professional |

| Multiple part-time | 38% | Clerk + lifeguard + musician |

| Full-time + side work | 21% | Engineer + weekend carpenter |

| Portfolio career | 9% | Writer + teacher + performer |

The 38% working multiple part-time positions represent the core commons employment model. They work fifteen hours at a library, ten hours at a café, eight hours as a swimming instructor. Each position constitutes genuine employment satisfying contributory service requirements and providing commons access.

This creates several effects: workers experience diverse workplaces and colleagues, social networks expand dramatically across sectors, class consciousness weakens through exposure to varied work, communities integrate workers from multiple sectors, and employment boredom decreases through variety.

-

While ruin might seem to exaggerate a fall to the basic comforts of unemployed life in Vekllei, the same is true at certain scales overseas – how many millionaires truly end up on the streets? The risk of losing power, resources, luxuries, respect and effort motivates success in Vekllei as it does overseas. ↩︎

-

Export licensing allows companies to profit off of surplus production, subject to permits provided by the Bureau of Surplus and Export. ↩︎