NEW Story: Cocktail

Phreaking

Part of the technology series of articles.

Read more: Photophreaking

Phreaking is the process of exploring photo or telecommunications infrastructure, usually in service of surveillance, signal interference or intelligence gathering. It is a practice often associated with the phreak subculture, and has legitimate technical and educational uses. More commonly, however, phreaking is performed without permission from a communications operator and can be used to surveil or tamper with information passing through a network. The term phreaking refers specifically to interactions with information in transit. This is in contrast to phracking, which describes intrusion into computers themselves, although a “phreak” is the nomenclature for people who either “phreak” or “phrack.”

Computers in Vekllei use optical circuits, and usually transmit information through fiber-optic cables called photolines. These are different from regular telephone lines, but are often bundled with them. A network of optical computing infrastructure is called a photocommunications network, which uses a packet protocol where light pulses of specific wavelengths and timing intervals represent both data and network control signals. Similar to how telephone systems used in-band signaling tones, photocommunications systems embed command sequences within the same channels as regular traffic.

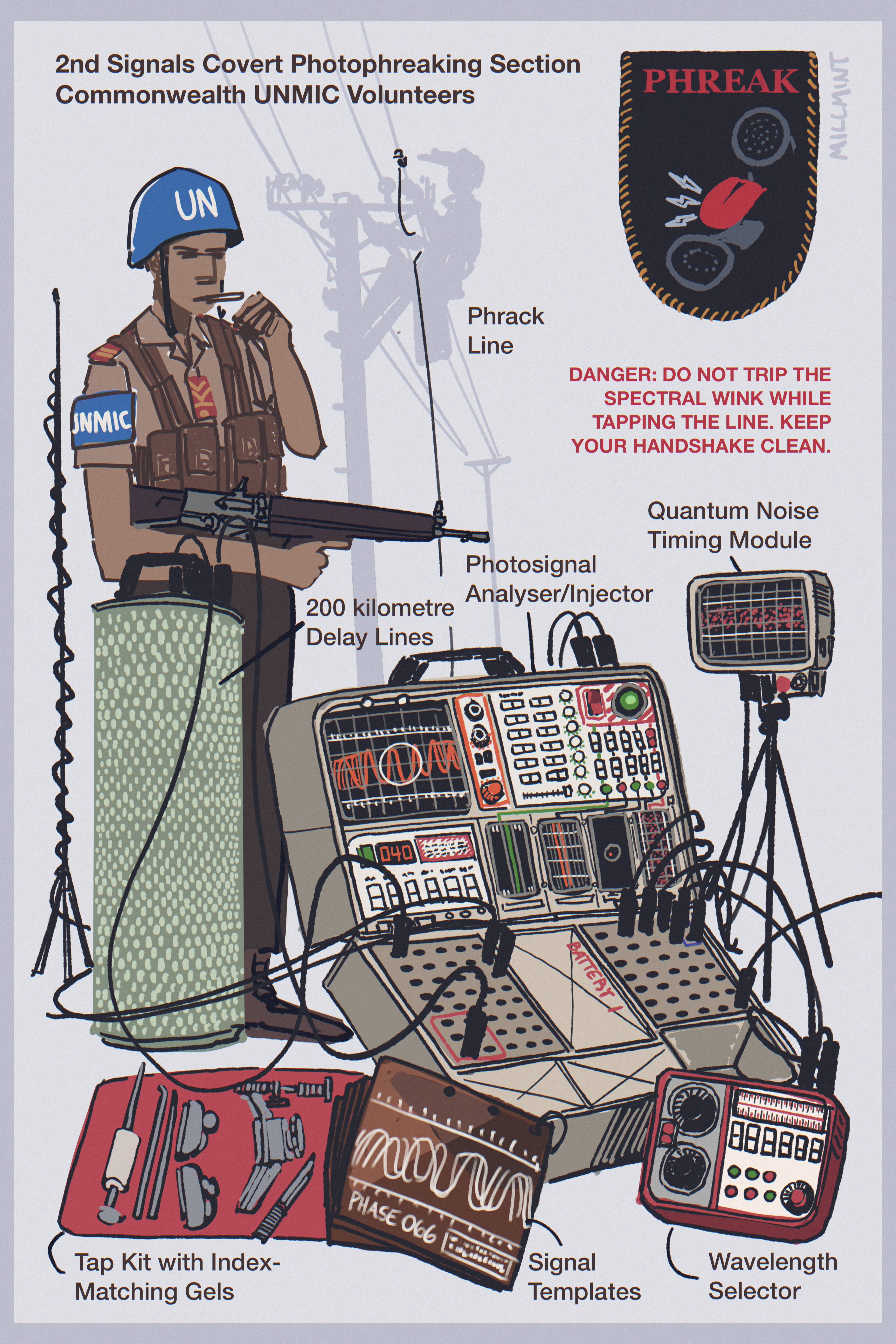

Photocommunications phreaking is highly technical, and involves the use of special equipment to make use of any intercepted signals. In covert applications, it follows a specific process:

- A photoline is “tapped” by exposing the optical cable from its shroud and bending it in a mechanical jig to allow light to leak out.

- A collection cable (a photodetector) is positioned at the bend in the line and an index-matching gel is applied, which facilitates the reading of the signal.

- If information is being injected into the line, a secondary injection cable is required.

Phreaking is not actually particularly complicated, but doing it covertly is extraordinarily difficult and can fail regularly. Photocommunications networks use specific command signals to operate, and interruptions to that connection can trigger a “spectral wink” that disconnects the line and can indicate a tap. Covert phreaking usually follows a series of steps:

- First, a phreaker establishes a physical connection described in the process above, and monitors the optical traffic to identify the specific wavelengths and patterns used for network control signals. The connection is routed through a delay line, which is usually dozens or even hundreds of kilometres of coiled cable that introduce microseconds of latency into the connection. The phreaker then observes the waveforms and patterns of the signal.

- Once the command signals are identified and decoded, equipment like a Photosignal Reader/Injector are calibrated to perform a mimic wavelength masquerade which generates signals that appear to come from a higher command authority computer. This process is sometimes called “a charade.”

- Bad signals, coming either from micro-interrupts caused by physical interference with the line or malformed signals injected into the connection, can trigger a “spectral wink” that closes the connection and may leave evidence of manipulation. Phreakers usually use the natural quantum noise floor of a connection to mask these interrupts, and time their interventions with these natural noise peaks. Some amount of artificial noise can be generated if the line is too clean.

- With the command signals decoded and the line monitored for noise that can mask the intrusion, command signals can then be injected to “join” an existing connection without disrupting it. This is called a “handshake” or “manipulated handshake.”

- Everything is now in place for a phreaker to surveil the connection or even inject new data. Further intrusion is possible (for example, to use physical proximity to a receiver to route traffic in the brief delay between caller and receiver) but this kind of tampering risks detection. A good tap, with good data and few interrupts, is very difficult to detect.