NEW Story: Cocktail

Photovolumes

Part of the technology series of articles.

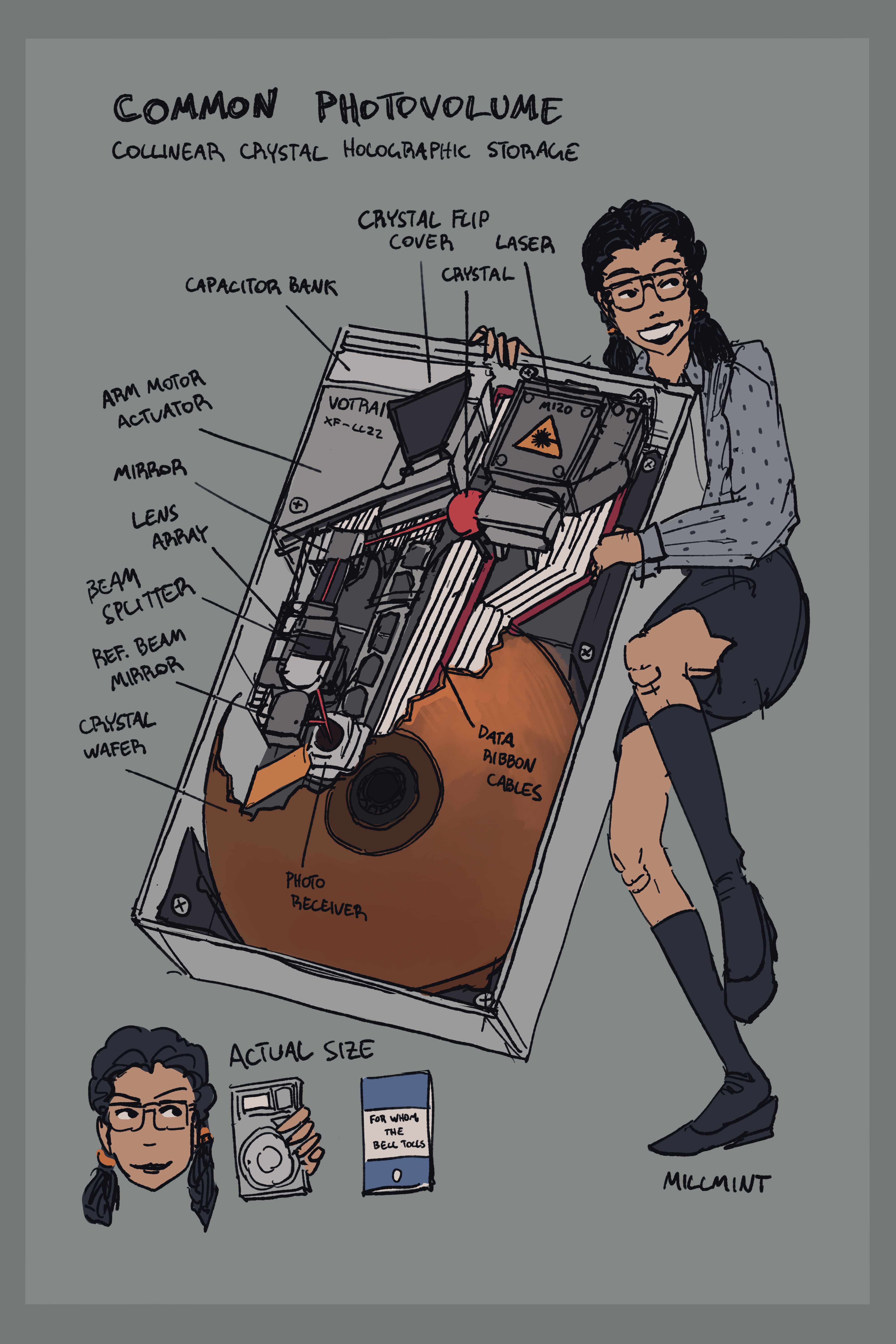

Computer data in Vekllei is stored in crystals known as photovolumes. Lasers record and retrieve data from these crystals, which convert the information into electrical signals for use in a computer.

Photovolumes are remarkable devices comprising many complex components. Since Vekllei computers do not use bitmapped screens, all graphics and images accessed electronically are effectively stored in miniature as holograms in the structure of the crystals, which are called photocrystals. In addition to images, regular ternary data can be written and read in parallel, and together form the basic memory components of a Vekllei computer.

Operation #

Photovolumes can store all kinds of data encoded as light wavelengths, including images. It first has to be recorded (encoded) into a light pattern, usually by projecting the image onto a photosensitive material like laserfilm.

This is done with a laser beam fired by a device called a light gun. It produces a laser that is split with a prism to form two distinct beams with different functions:

- A signal beam, which is pointed at an object and shines at its surface. This light scatters around and carries information about the object, like its shape, texture and details. This laser shines between the object and the photocrystal recording medium.

- A reference beam, which is pointed at the photocrystal. This is a clean, unaltered signal.

When the two beams meet at a superposition, they interfere with each other, creating what is called an interference pattern. This pattern is a complex map of the image (or data) including its shape, texture and details. The pattern encodes the amplitude (brightness) and phase (wave shape) information of the object into the crystal. This works like a pen and ink, with the reference beam providing a steady flow of unaltered ink and the signal beam shaping it.

Light interference occurs where the waves of both beams meet, creating bright spots. Dark interference occurs where the waves are misaligned, where the peaks of one amplitude meet the troughs of another, creating dark spots. These light and dark spots are known as constructive and destructive interference patterns respectively. These light and dark spots affect the photocrystal, and form a pattern that can be read back to reconstruct the data.

In Vekllei, there are two main types of photocrystal in use in commercial photovolumes:

- Photorefractive photocrystals can be read and overwritten over and over again, making them useful to store data that needs to be updated, moved or deleted. There are two kinds of photorefractive photocrystal used in commercial photovolumes in Vekllei:

- Lithium Niobate (LiNbO₃), which is more durable and well-suited for the nonlinear optical computing used in Vekllei thanks to its good piezoelectric and photoelectric properties.

- Barium Titanate (BaTiO₃), which is more photorefractive and faster to read and write from, at the expense of durability. This is often used as a form of cache in large memory archives.

- Photopolymer photocrystals are written to once before hardening, permanently fixing the data patterns in place. In this state, it is able to be read over and over again. These photocrystals form the basis of Vekllei archive volumes, and will last a very long time. Once written to, however, they typically cannot be overwritten.

As the beams move across the surface of the photocrystal, they affect its physical properties. Depending on the type of crystal, constructive interference may affect its density, refraction index or its light absorption qualities. This occurs on a microscopic scale, in billionths of a meter.

To retrieve the information, the reference beam is pointed at the crystal at the same angle and conditions. As it strikes the interference pattern it refracts the reference beam, which reconstructs the original signal beam’s wavefront. This wavefront is fed into a photodetector, which translates the shape of the waves into ternary data that a computer can understand. Images signals are passed through directly, cached and positioned by metadata.

Design #

Vekllei commercial photovolumes are typically the size of a paperback novel. They can interface with optical computers and are plugged in via a photovolume port, which contains the photodetector required to parse the wave data from a photocrystal.

Inside a photovolume there is a head assembly consisting of a laser, beam splitters and mirror arrays to deflect the beams. There are also electrical components required to interface with a computer.

The data in the drive is stored in trays, which contain crystal wafers derived from a larger crystal boule. These look like very thin disks, and have a large surface area to read and write data to. In most commercial photovolumes, there is a smaller tray called a cache that uses higher-performance crystal wafers for temporary storage to increase data retrieval speeds.

Storage Information #

In ternary computing, the smallest kind of data is called a trit – three values that make up a single character. Photovolumes store trits and physical images alongside each other to store useful data for computers.

Scientific ternary units are represented as Metr, Gitr, Tetr and so on. In common use, an ‘ah’ sound has been appended to most of the units to make them easier to pronounce.

Photovolumes typically have a storage density ranging between 100-200 tetra per square inch. A typical commercial drive might have a storage capacity of 5,000 tetra, or 5 petra.

| Unit | Number of Trits | Equivalent in Base-3 |

|---|---|---|

| Trit | 1 | 3^0 |

| Kitra (Kit) | 1,024 | 3^10 |

| Metra (Metr) | 1,048,576 | 3^20 |

| Gitra (Gitr) | 1,073,741,824 | 3^30 |

| Tetra (Tetr) | 1,099,511,627,776 | 3^40 |

| Petra (Petr) | 1,125,899,906,842,624 | 3^50 |

| Etra (Etr) | 1,152,921,504,606,846,976 | 3^60 |

| Zetra (Zetr) | 1,180,591,620,717,411,303,424 | 3^70 |

| Yotra (Yotr) | 1,208,925,819,614,629,174,706,176 | 3^80 |