NEW Story: Sunday Morning

Spatial Economics in Vekllei

Part of the bulletin series of articles.

Summary

- Physical space shapes economic behaviour in ways conventional economics often ignores.

- Vekllei’s universalised housing systems create modest homes with few private entertainment systems, pushing residents into public space.

- This “architectural austerity” isn’t orchestrated deprivation but an organic consequence of design choices that aligns behaviour with the commons economy.

- Consumption shifts from private goods to public participation, reinforcing the ludic economy’s social foundations.

Vekllei has completed a ‘spatial turn’1 – we know by now that homes, shops and parks are not just backgrounds to meaningul activity but participants in it, upstream and downstream. A school is more than just a place of education; a home is more than just a place to sleep, and so on. Knowing this, the architecture of Vekllei life asserts itself not just in the cliches of urban planning but as something social, organic and relational. In turn, places themselves shape economic behaviour.

American economist Juliet Schor observes that suburban houses don’t just shelter families but generate consumption – big houses require filling, they necessitate cars for access, and the isolation they create gets compensated through shopping.2 This relationship between space and spending seems obvious once stated, yet conventional economics treats housing as neutral infrastructure rather than behaviour-shaping architecture.

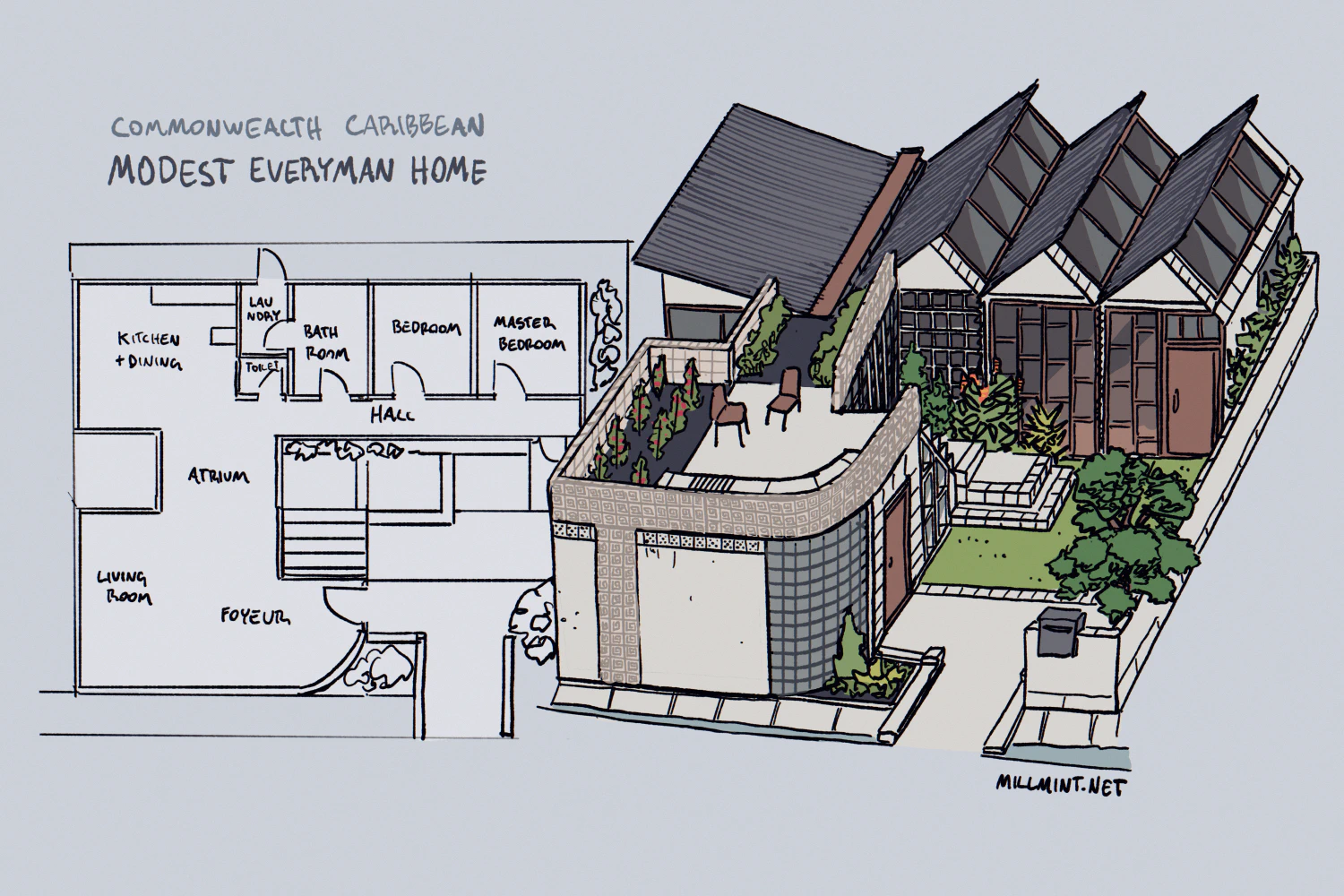

If America in 2063 indulges a modern consumer society, Vekllei inverts this pattern. Housing in Vekllei must be provided universally, and the organic products of this system are modest homes, compact apartments and rowhouses – typically 40-60 square metres for a family of three. Homes lack television sets, formal dining rooms and the home theatre systems common in wealthy nations. Such is the petty poverty of universal access, and it creates distinct economic behaviours impossible in sprawling suburban environments.

The Density Dividend #

Urban economist Edward Glaeser argues that density creates economic efficiency through reduced consumption, noting energy savings from smaller homes, shared walls and reduced transport needs.3 But forcing consumer sacrifices for these abstract efficiencies is unsympathetic; these calculations miss the basic behavioural shifts that matter more in Vekllei’s social economy.

When homes become too small for elaborate entertaining, social life migrates to public space. When private recreation becomes boring, public amenities become essential infrastructure. In this sense, the cinema isn’t a commercial venue but social architecture. The library isn’t just books but a living room. The park isn’t decoration but necessary space for activities impossible in compact apartments, and so on.

This pattern appears most clearly in Tokyo, where housing constraints have created elaborate public infrastructure. Research on Japanese bathing culture examines how small apartments push residents into communal spaces like public baths, cafes and parks. These become “third places” where social and economic activity that would occur privately in suburban America happens collectively.4 The built environment doesn’t just stage behaviour but influences it; and so the ‘spatial turn’ emerges.

Compensatory Publicness #

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett describes how urban density shifts consumption patterns toward services and experiences rather than material goods.5 In Vekllei, this shift becomes total. Without home entertainment systems, cinema becomes social infrastructure rather than commercial enterprise. Without elaborate kitchen appliances, restaurants and cafes become extensions of domestic life rather than special occasions.

This represents what might be called compensatory publicness. Small private space requires large public space. Limited home amenities demand elaborate public amenities. But “compensatory” suggests loss being made up, when really it describes different allocation of pleasure. The cinema provides social ritual alongside moving pictures; the café provides community membership alongside coffee, and so on. Centralising these activities can make the places they occur much more beautiful – grander and more decorated than any living room – though undoubtedly less convenient.

This behaviour aligns organically with the ludic economy and illustrates the symbiotic relationship with spatiality and economic behaviour. Private entertainment isolates individuals in homes, making economic activity transactional and atomised. Public entertainment creates visibility, sociability and the kind of participation from which ludic work emerges. Anyone familiar with how Commonwealth society works will recognise this immediately.

Natural Sociability #

Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third places” to describe essential community spaces beyond home and work – cafes, bookshops, public baths and parks where civil society forms.6 In suburban America, these barely exist. In Tokyo, they become crucial infrastructure. In Vekllei, they become the primary venue for economic life itself.

This creates what might be called a natural sociability. Without space for private recreation, residents must venture into public. Without personal entertainment, they seek out shared amusement. In Vekllei it is almost impossible not to know your neighbour; the built environment shapes behaviour like oases shape the life of a desert.

It is no wonder foreigners are caught off guard by the general sociability, wit and courtesy of the regular Vekllei person. Their economic behaviours are their social behaviours, which are their recreational behaviours, which are their private behaviours. The ludic economy depends on visible participation, which is their fundamental currency.

This connects directly to courtesy. If economic relations are primarily social, and social relations happen in public space, then courtesy becomes economically rational behaviour. Being rude in the cinema matters when you’ll encounter those same people at the library, the tram stop, the workplace. The density of public life creates density of social obligation.

Temporal Economics #

Without home recreation, there’s pressure to fill leisure time productively. Television’s great achievement was making time disappear. It fills hours without effort or skill or really anything at all. Remove it and those hours demand filling with something else.

In Vekllei, that something else becomes conversation, craft, boredom, sex, play, work, tinkering, writing, drawing, loitering, drinking and reconnection. These are the same features of a ludic economy. With limited home entertainment, residents take up hobbies that require public space and social participation. They join musical groups, attend lectures, participate in workshops, play sports. These activities don’t just pass time but generate the kind of enthusiastic participation that makes moneyless work function, and contribute to the calibre and talent of Vekllei people.

Schor describes how American consumer culture creates cycles of “work-and-spend” where long hours generate income for goods requiring further work to maintain.7 Vekllei’s spatial economics breaks this cycle. Small homes can’t accommodate many goods. Limited private space reduces maintenance burden. Time freed from consumption gets redirected toward participation.

This isn’t asceticism but different allocation of attention. Instead of maintaining elaborate homes and entertainment systems, residents maintain social relationships and participate in communities. Instead of accumulating private goods, they accumulate status and pleasure through visible contribution and its rewards. The architecture shapes their desires toward things the commons can provide. It is no more coercive than consumer society, or any other kind of modern and dignified living – anyone who tells you otherwise is a fool.

Architectural Austerity as Social Abundance #

What appears as architectural constraint becomes social possibility. Modest living pushes residents together. Limited private amenities create demand for public infrastructure. Absence of personal entertainment systems generates need for common recreation. Each constraint generates corresponding abundance in public life.

This is undoubtedly a conscious choice on the part of the Bureau of Housing and Bureau of Residences and Factories. This practice has been going on since the independence and has only intensified. Vekllei’s postwar reconstruction could have built suburban sprawl with elaborate private homes. Instead, it built dense communities and invested in public amenity. This was not a punishment or chintziness but a confluence of design instincts that over time validated certain spatial arrangements within their emerging commons economy.

Glaeser argues cities function as centres where people gather to exchange ideas, goods and culture.8 Vekllei’s cities are places where people gather to trade time and attention, facilitated by good architecture and sophisticated design. The built environment is not just the house of the economy but the shape of it.

This emphasises both the ordinary and wondrous aspects of Commownealth living. They are not more good hearted, altruistic or perfect than you. Give them suburban homes with television sets and they’d likely behave like Americans. Keep them in pretty, modest houses without private entertainment and they behave like Vekllei people, socialising in public space as they develop natural responses to their built environment.

The revolution, such as it exists, happens in bricks and floor plans rather than consciousness. Change the space and you change the behaviour; change the behaviour and you change the economy.

The cinema, the café, the library, the park – they are economic infrastructure as crucial as factories or railways. They provide the space where social relationships form, where status is recognised, where the ludic economy’s enthusiastic participation becomes organic. Remove them and the commons collapses. Strengthen them and moneyless work becomes natural rather than utopian. This is the ‘spatial turn;’ this is what it means. The quality of Vekllei cities and towns is the engine by which everything turns.

-

See The Spatial Turn, 2008, by Barney Warf and Santa Arias. ↩︎

-

In The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need, Schor examines how suburban housing patterns generate consumption cycles and material accumulation. ↩︎

-

In Triumph of the City, Glaeser documents how urban density reduces energy consumption through smaller living spaces and reduced transportation. ↩︎

-

Research on Japanese bathing culture, including studies of public baths (sento) and hot springs (onsen), demonstrates how architectural constraints create social infrastructure. See various works on Japanese spatial culture and urban anthropology. ↩︎

-

In The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class, Currid-Halkett examines how urban living shifts consumption toward experiences and services. ↩︎

-

In The Great Good Place, Oldenburg defines third places as neutral gathering spaces essential for civil society. ↩︎

-

In The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure, Schor documents increasing working hours despite productivity gains, driven by consumer culture. ↩︎

-

See again Edward Glaeser’s Triumph of the City. ↩︎